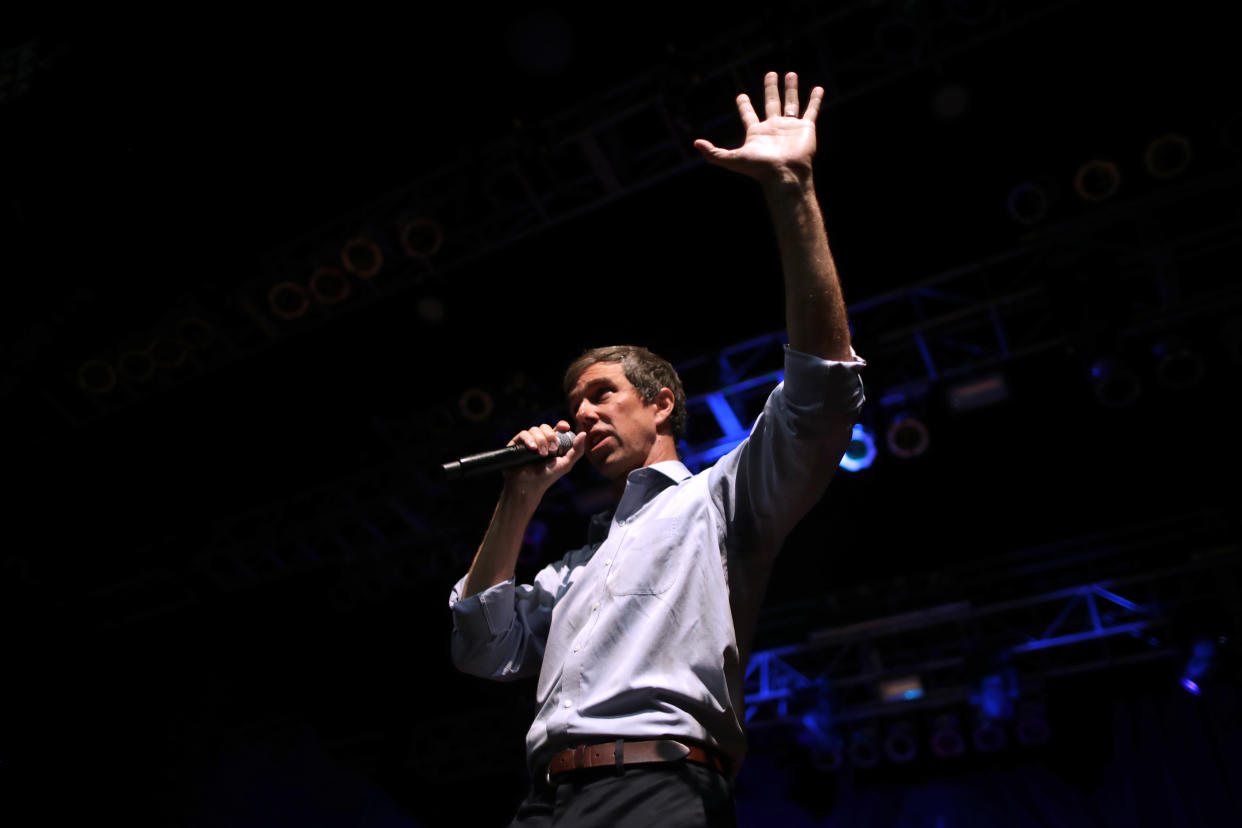

Beto's unlikely quest to unseat Cruz comes down to Austin, Dallas, Lubbock, Midland ... and everyplace else

EL PASO, Texas — After hundreds of rallies, more than $100 million in campaign contributions and massive national media attention, Texas’s surprisingly close U.S. Senate race between Republican Ted Cruz and Democrat Beto O’Rourke wound its way to the finish line Tuesday as the candidates returned to their respective hometowns to watch and wonder how the election will ultimately end.

As voters headed to the polls to render the final verdict on what has become one of the most closely watched races in the country, the question raised by people across the political spectrum was largely the same: Could Beto really win?

O’Rourke, a three-term congressman from El Paso who was a political unknown even among members of his own party until this race, is vying to become the first Democrat elected statewide in Texas since 1994 — and the first elected to the U.S. Senate from the state since 1988. Until recently, that seemed like a hopeless quest in deeply conservative Texas, a state that has moved further and further to the right since George W. Bush defeated Ann Richards, the sitting Democratic governor, in a stunning upset that put Republicans firmly in control of the Lone Star State 24 years ago.

But O’Rourke shunned the mechanics of traditional campaigns. Eschewing the traditional route of hiring high-priced consultants and pollsters, the congressman charted his own path, running a social-media-heavy campaign in which he served as his own strategist. He hired a handful of aides — most of them personal friends from El Paso who had little to no political experience — and rented a van from which he began live-streaming most of his waking hours. He presented himself as a genial and unapologetically liberal counterpoint to the combative presidency of Donald Trump and toxic partisanship he says has been championed by Cruz, a tea party Republican who was elected in 2012.

Along with two young aides who have served as traveling companions and co-stars in his rolling reality show, O’Rourke drove all over the state, charting a path that took him beyond the big cities to the smallest towns of rural Texas — deeply conservative areas where politicians, Democrats or Republicans, rarely showed up. “How can you win in those areas if you don’t try?” he asked last summer. While Cruz and his aides blew him off at first, O’Rourke soon gained notice for his rock-star-size crowds, especially those in unlikely places like Amarillo, Longview and Wichita Falls, some of the reddest cities in Texas.

O’Rourke would ultimately visit all of the state’s 254 counties — becoming one of the first, if not the only, statewide candidates to do so — and loop back again, driving hundreds of thousands of miles trying to reach the sleeping giant of Texans in a state where less than half of those eligible to vote actually show up at the polls. Along the way, the congressman made the race surprisingly competitive. Though O’Rourke never led in a single poll conducted in the race, last-minute race surveys found him locked in a statistical tie with Cruz — a stunningly close result in a campaign that was supposed to be an easy ride to victory for the Republican senator.

O’Rourke, who never hired a pollster, has expressed skepticism about whether the polls captured the full breadth of his support, arguing that he has sought to expand the electorate by targeting “non-voters” and young people who might not show up in a sample survey of likely voters.

Cruz entered the race with a wide structural advantage, in part because there are simply more conservatives than liberals in Texas. Until recent days, internal GOP polls showed that he held a 6- or 7-point advantage over O’Rourke, according to Republicans close to the campaign. But massive voter registration numbers and the record-breaking early vote turnout has thrown Cruz’s hold on the seat into uncertainty, in part because the voting electorate appears to have expanded.

Texas registered a record 15.7 million voters this year — about 1.7 million more than the state had in 2014, the last midterm elections. As of last Friday, nearly 4.9 million votes had been cast through early voting and absentee ballots in the state’s largest 30 counties, where nearly 80 percent of Texas voters live. That number was higher than the entire turnout of the 2014 election. On Monday, Derek Ryan, a GOP consultant and former research director at the state Republican Party, projected a total voter turnout of 8.2 million — almost on par with turnout in the 2016 presidential election. According to the Texas secretary of state, no midterm election in state history has attracted more than 5 million votes.

Both Cruz and O’Rourke claimed to have gained momentum from the record-breaking numbers. And they have both barnstormed through rural and urban Texas, seeking to shore up their political firewalls in advance of Election Day.

The question of whether O’Rourke can make history will be decided largely in the state’s largest cities. His campaign is banking on historic turnout in Democratic strongholds like Austin, Houston and Dallas. Republicans have long won most of their campaigns by driving up the votes in deeply red conservative Texas — places like Tyler, Lubbock, Midland and Beaumont, where Cruz has made repeated visits in recent months. For Cruz to win, he needs rural Texans to turn out the way they do in a presidential year.

But O’Rourke has sought to undermine the usual GOP playbook in his pursuit of votes in rural Texas. While the congressman has said he never expected to outright win in those regions, he is hoping to win just enough votes there to add to what he hopes will be massive turnout on his behalf in the cities. His success or failure largely rests on whether his gamble on rural Texas pays off.

On Tuesday, there are a few regions both campaigns will be watching, including the suburbs of Houston, where the GOP hold on power has been thrown into doubt by a rapidly diversifying electorate. Both campaigns will be watching Amarillo in the Texas Panhandle, where Cruz is likely to win but where O’Rourke has found a following among progressive evangelicals opposed to the administration’s crackdown on refugees. And they will be watching Longview in East Texas, another area Cruz should win but where O’Rourke has attracted massive crowds.

But the mostly closely watched counties are likely to be in the Dallas/Fort Worth area — including Denton County and Collin County, which have tended to back Republicans but where Democrats appear to be surging. One of the most closely watched House races in the country is Texas’s 32nd Congressional District, which includes Collin and Dallas counties. GOP Rep. Pete Sessions has been statistically tied in the polls with Colin Allred, a former NFL player turned voting rights attorney, in a race that has been driven in large part by the debate about access to health care. The race is considered a bellwether for O’Rourke’s chances in the Dallas region.

Perhaps the most closely watched county of all, however, is Tarrant County, which includes Fort Worth. It is the last big Republican city in the state — and one that O’Rourke has focused on flipping, appealing to black voters and new voters. If the city votes Democrat, Republicans suggest Cruz is in big trouble — which is why the junior senator from Texas stopped there late last week, calling it the “biggest, reddest county in the biggest reddest state” — and one he needs to win.

“As Tarrant County goes, so goes the state,” he said. The returns will show whether he is right.

_____

Read more Yahoo News midterms coverage:

In Texas Senate race, both parties are at the door — all 7.4 million of them

Battle for the soccer-mom vote plays out in suburban Detroit

Menendez race pits ethical concerns against party loyalty, and loyalty is winning

A House rematch sheds light on how landscape changed from 2016

Virginia Republican congressman tries to weather scandal and wave of spending