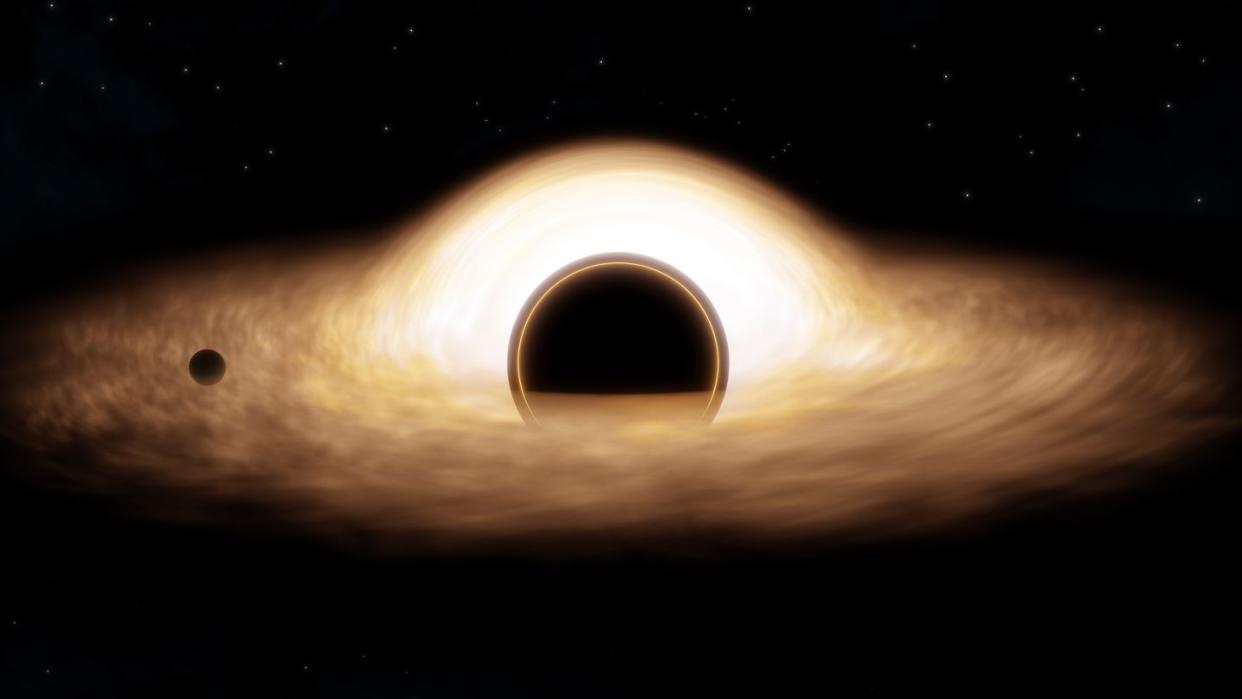

Astronomers Discovered a Once-in-a-Lifetime ‘Sleeping Giant’ Black Hole

Stellar mass black holes, which are significantly smaller than their supermassive cousins, usually weigh in at around 10 solar masses. But the European Space Agency just found that’s more than 3 times that size.

Located nearly 2,000 light-years away in the constellation Aquila, this black hole—named BH3—was discovered when astronomers analyzed the wobbly orbit of its companion star.

This makes BH3 the largest known stellar-mass black hole in the Milky Way, supplanting the previous record holder, Cygnus X-1, which weighs only 21 solar masses.

There are a few kinds of black holes in the cosmos, and these perplexing celestial objects are categorized by mass. As their name suggests, supermassive black holes—like Sagittarius A*, which lies at the center of the Milky Way—are the big boys of the universe, weighing in at a mind-boggling 4.3 million Suns. On the smaller end of the spectrum (relatively speaking) are stellar black holes.

While NASA and other space agencies are actively searching for answers to how supermassive black holes form, stellar black holes typically take shape when stars (that were originally 20 solar masses or more) explode into a supernova. If the star was between 8 to 20 solar masses, it usually condenses down into a neutron star. Our Sun, for what it’s worth, probably won’t share either of these fates, and will instead transform into a white dwarf and, in 10 trillion years, a black dwarf.

So, while stellar black holes don’t impact the universe quite like their supermassive counterparts, they’re solidly the silver medal recipients when it comes to massive objects in outer space. Most stellar black holes clock in at around 10 solar masses on average, but some impressive outliers do exist. For example, the first black hole ever discovered—Cygnus X-1, which is located 7,000 light-years away from Earth—clocks in at an impressive 21 solar masses.

But the European Space Agency’s Gaia (which is also busy building the world’s largest 3D map of the galaxy) has now spotted a new heavyweight champion—a stellar black hole in the constellation Aquila somewhat uninspiringly named Gaia BH3. And the discovery caught the Gaia team completely by surprise. A paper detailing the discovery was recently published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

“No one was expecting to find a high-mass black hole lurking nearby, undetected so far,” Pasquale Panuzzo, an astronomer from the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) at the Observatoire de Paris, said in a press statement. “This is the kind of discovery you make once in your research life.”

Buried in the mounds of data that makes up Gaia’s Data Release 4 (DR4), BH3 is actually in a binary system with a star, which is how scientists detected this well-hidden black hole in the first place. Often, stellar-mass black holes will be only one member of an “X-ray binary,” where the black hole is slowly consuming its host star and producing X-rays in the process. However, BH3 is too far from its companion to consume material, meaning its dormant. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t influencing its stellar neighbor.

Scientists closely examined the star’s wobbling 11.6-year-long orbit, which is an average of 16 times Earth’s distance from the Sun (though, at its furthest, its about as far from the black hole as Neptune is from our Sun), and determined that there must be a massive invisible partner influencing its trajectory. The team checked its findings using ground-based observatories, including ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile’s Atacama Desert, and confirmed the results.

Scientists have previously theorized that stellar black holes form from metal-poor stars, which are stars with only small amounts of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium. The thinking goes that these stars lose less mass during their lifetime, so they have more material when they collapse into a black hole. While ESA can’t measure BH3 directly, it’s companion star offers up some clues, as binary stars often share similar compositions. The star appears to be metal-poor, as scientists have predicted, but the team that discovered BH3 can’t be sure if it captured this star before or after its formation.

“What strikes me is that the chemical composition of the companion is similar to what we find in old metal-poor stars in the galaxy,” Observatoire de Paris’s Elisabetta Caffau said in a press statement. “There is no evidence that this star was contaminated by the material flung out by the supernova explosion of the massive star that became BH3.”

And the best part? ESA describes this discovery as a “tasty appetizer” for what’s ahead, saying the BH3 was so exciting that they decided to spill the details before Gaia’s official DR4 release. In other words, more amazing space data is on its way.

You Might Also Like