'It's a sham': Spouses, families raise alarm on adult protection laws

Beverly Shaw drove around Indianapolis in a 2014 blue and black Hyundai Sonata with two goats and a binder of evidence, page after page of pictures, medical papers, hand written notes and legal documents that she hoped would help her win guardianship of her husband of more than four decades.

"I remember telling David years ago, I said 'don't worry about getting old. I'll wipe your hiney if I have to, I love you so much,'" she said recently, explaining her tireless crusade. "I'm just trying to get him out and go back home."

Back home to their farm in Missouri, that's where the goats were raised. He loved them, she said, and their life together — until he fell sick on a trip to Shelbyville.

David wound up in a Shelbyville hospital where health care providers questioned Beverly's ability to care for her husband. She quickly lost guardianship, or the power to make decisions for David, to a county program and struggled in court for more than six months to see that power go to a family member. During that time, David was transferred from the hospital to a Shelbyville nursing home, hundreds of miles from the Shaws' Missouri residence.

The Shaws' story is a complicated one that reveals flaws in the system set up to protect some of society's most vulnerable individuals. And, say advocates, it shows that the guardianship system set up to safeguard against exploitation by unfit family members is in need of safeguards of its own.

There's not enough done to keep guardianships in the family, said Rick Black, a national advocate for guardianship reform based in Charlotte, N.C. If families are not on board with the plan, they may find themselves fighting a lopsided case in which they may struggle to find and or afford a lawyer.

"Guardianships were designed to be paternalistic and benevolent, but over the last few decades, adult guardianship has lost its way," Black said. "It's too often used as a weapon to yield power over vulnerable individuals with often complete disregard for the obligation to care and comfort (the individual) and conserve the estate."

Lauren Rynerson, the director of The Volunteer Advocates for Seniors and Incapacitated Adults of Shelby and Johnson County, said the organization does its best to involve family members in these cases before assigning a guardian. The organization also works to connect family with legal aid when they can't afford representation, she added.

Approximately 1.3 million Americans are under guardianship, some in troubling situations, according to a 2018 study by the National Council on Disability. Many guardianships, under lawyers, professional guardians or social workers, are imposed despite lack of facts or evidence showing that it's warranted, according to the study. Courts also lack resources to hold guardians accountable and prevent them from exploiting their wards, by drawing off of their savings or other assets.

The American Bar Association recognizes the need for guardianship reform and has called for a national standard to ensure representation for families.

The Shaws' story, along with those of two others who tangled with the process when a loved one could no longer make his or her own decisions, highlight how the system can go awry. In both cases the guardianship system targeted their homes, including one in which a judge assigned a professional guardian to oversee the estate of a deceased family member against the wishes spelled out in his will.

No legal representation

Beverly's defiance of doctor's orders, her uncompromising personality, financial struggles to keep up with the bills and unorthodox decision to keep her goats with her as she drove between Missouri and Indiana may have contributed to concerns about her ability to care for her husband.

In fact, her all-or-nothing spirit, inspiring to some but grating to others, prompted her to take her goats to the streets of New York City last fall to raise attention to her plight. She spun that trip into features in national media, including the New York Times. And she spun that coverage into more than $26,000 GoFundMe funding to help pay for hotel bills and travel.

"Everybody was behind me and said 'this is horrible,'" she said, referring to those she encountered in New York.

The nursing home that cared for her husband said patient privacy laws prevented them from explaining why David Shaw had been moved into public guardianship.

Black, who helped Beverly navigate her guardianship fight, said he believes Beverly did need help caring for David and the Shelby County public guardianship office should have done more to find support with the family before putting someone outside of the family in control of David.

Families who lose guardianship can't sue nursing homes, making guardianship an attractive option for nursing homes when there's tension with families, he said.

Nursing homes and lawyers can challenge a family's guardianship for a loved one for a number of reasons, ranging from concerns over a family member's ability to care for the loved one to a family falling behind on payments. Families can lack the resources to fight back as finding a lawyer to take these cases can be difficult and expensive.

One way to fix the inequity would be to follow Nevada's example and guarantee free legal representation to represent the individual and their family, Black said. Another solution, he said, is to require video recordings of the court hearings to hold judges and attorneys accountable. Right now, it's too easy in most states to remove a family member from guardianship, he said.

"Here is a perfect storm of a bunch of disparate systems converging on each other," he said.

Shaw combed through law firms before finding a lawyer, who later dropped her as a client.

Losing the house

Amber Mitchell lost guardianship of her mother's northwestside home, where she was living at the time. Court documents show Mitchell failed to pay nursing home bills and fill out paperwork showing financial hardship.

Professional guardian Debra Woods was assigned the case first to make financial decisions. A few years later the court gave Woods full guardianship of Mitchell's mother.

But Mitchell said that Woods did not invest much time in her mother's care.

"It's a sham," she said. "She only made a visit every six months. She might see my mother twice a year."

Woods was part of a Bloomberg investigative series on guardianship titled: 420 Cases, One Guardian: System Runs Amok on Just $35 a Month. In the series, Woods tells the reporter that she needs to have the heavy caseload to make ends meet, earning more than $7,000 a month for the more than 200 plus guardianship clients she oversees at one time.

Woods declined an IndyStar request for comment.

In 2022, after receiving court approval, Woods sold Mitchell's mother's house to pay nursing home debt and to ensure that Mitchell's mother remain in the home, court records show.

Amber Mitchell was living in the house before it was sold. Shortly after the house sold, Mitchell's aunt received guardianship of her mother and moved her to Nebraska, where she lives.

Billing dispute turns ugly

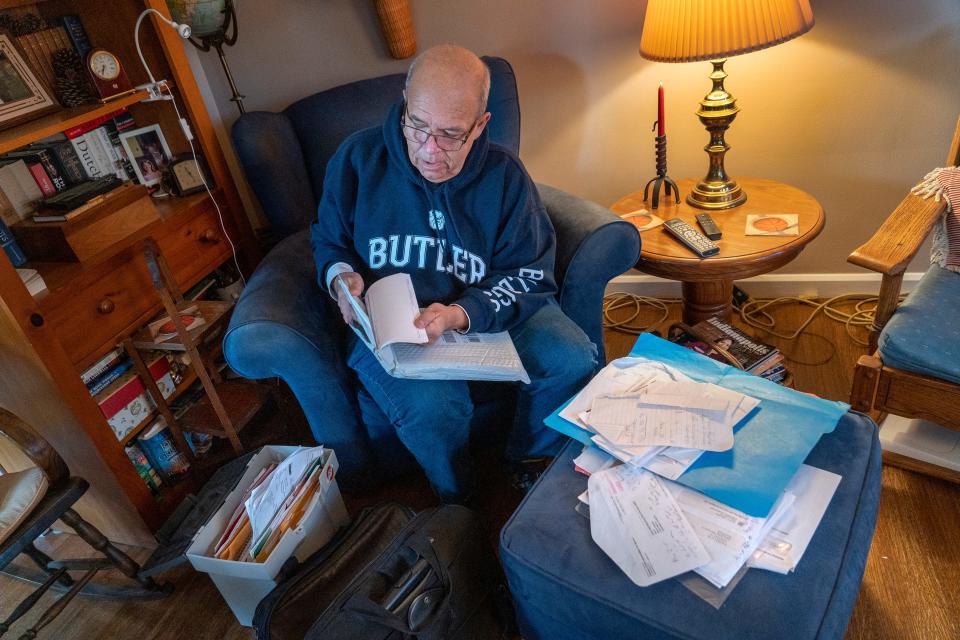

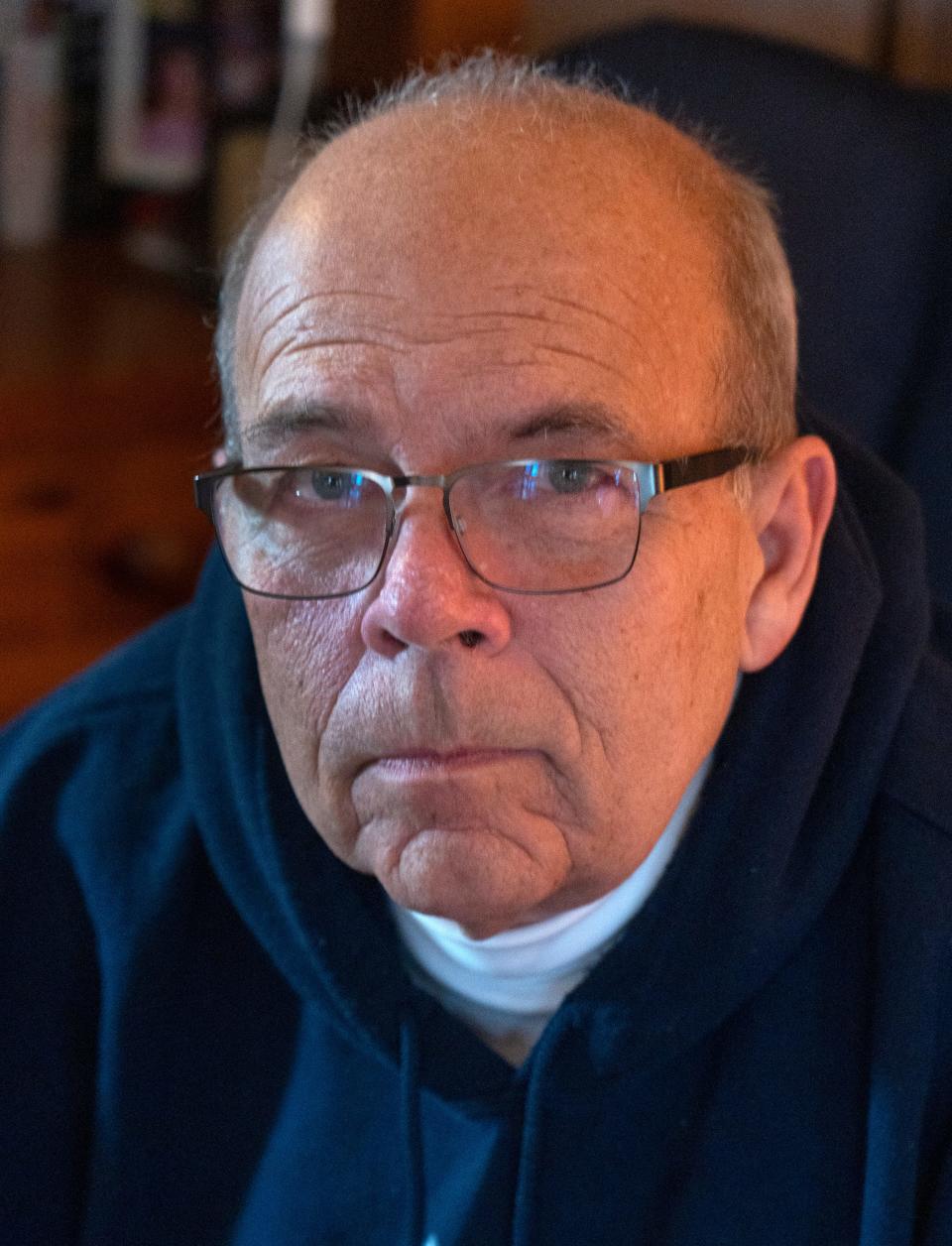

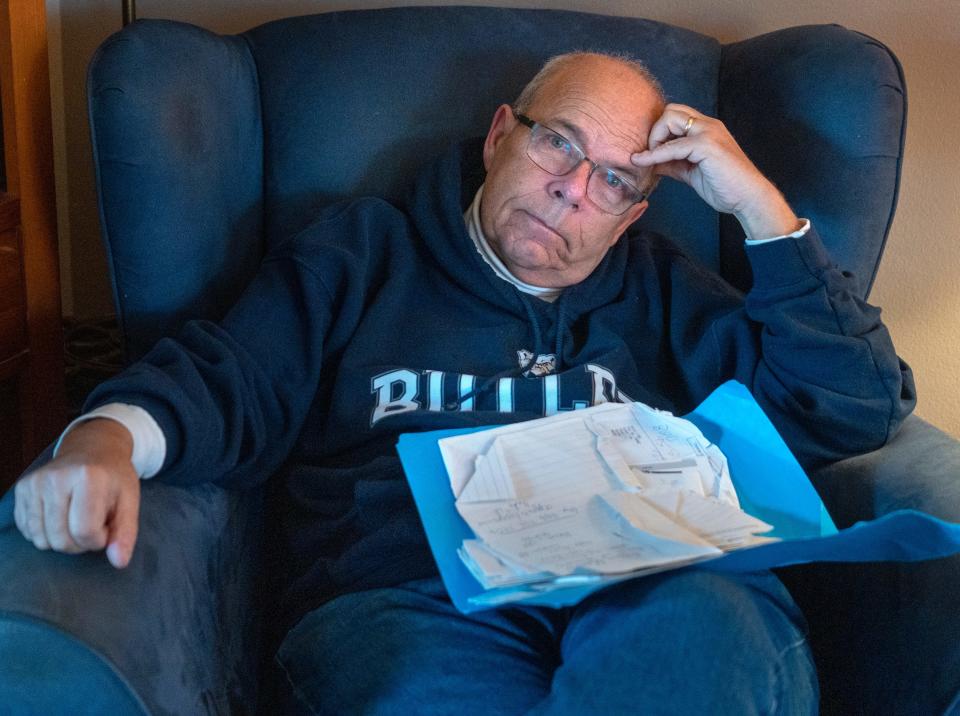

Marty Weyand, a Speedway resident, didn't lose control of his father's affairs until after he died.

His father had spent the last few years of his life at Trilogy Health Services in Warsaw, Indiana, getting treatment for COPD and a host of other chronic health problems. In those years, Weyand made decisions about his treatment and paid his bills.

The family's relationship with the nursing home was rocky. There were multiple disputes over payments. The nursing home didn't bill Medicare in time to get paid, sticking Weyand with the bills. The home also mistakenly put his father in a larger room, he said. To make matters even worse, he alleged, the checks he sent the nursing home weren't applied to his father's account.

This type of problem is fairly common, according to the National Consumer Law Center. Nursing homes can make mistakes in applying for Medicare or Medicaid coverage and then aggressively try to collect disputed bills.

After Weyand's father died in 2021, tens of thousands of dollars were still in dispute between the nursing home and the family. So in 2022, a lawyer representing the nursing home petitioned Kosciusko Superior Court to assign a personal representative, a lawyer and professional guardian Stacy McGuyre, to replace Weyand to control the estate.

McGuyre said she's a neutral party in the dispute, a characterization with which Weyand disagrees. She said while some documents support Weyand's side of the story, she concluded Weyand's father had a debt that needed to be paid and explained that the dispute was due to Weyand misunderstanding of his father's insurance.

Weyand has received requests from McGuyre and the nursing home attorney seeking to take his father's house in Kosciusko county as well as his own house to pay the disputed debt. McGuyre said that the attempt to seize Weyand's house was a clerical mistake.That's no solace to Weyand.

"I've been living in this hell for two years and I'm about at the end of my wits," he said.

Like Shaw, Weyand has a binder where he's kept financial records, medical information, testimony, payments and correspondence with the nursing home, Trilogy, that took care of his dad.

That way, he has proof that the nursing home failed to submit for Medicare reimbursement. He has documents showing he was mistakenly charged for a larger room. He has a letter from his father's insurance company, saying that he should not be held responsible for billing errors on the part of the nursing home. He has copies of checks that were cancelled and correspondence from the nursing home demanding those same charges be paid. Trilogy officials did not comment on the case.

Early this year, Weyand settled with the nursing home for $50,000, after his lawyer estimated that dragging out the legal case could cost him more than that.

What's Next

Recently, a compromise was reached in David Shaw's case in which David moved into a nursing home in Missouri under the guardianship of his and Beverly's son, Jeremiah Shaw.

Jeremiah Shaw confirmed that he was appointed guardian but declined to discuss the case further.

The nursing home in Missouri is about an hour and a half from Beverly and David's home.

She's hopeful that David will recover fully and they will be together soon.

"It may take time, money. I said, I'm never giving up on getting you home," Beverly said.

Binghui Huang can be reached at 317-385-1595 or Bhuang@gannett.com

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Flaws in Indiana's guardianship system concern families, advocates