Addressing the gap: The demand for climate education in Mohawk Valley schools

The Oneida-Herkimer-Madison BOCES Science Center just hosted the region’s second Youth Climate Summit, a free event which aims to engage middle and high school students in climate adaptation solutions.

Schools nationwide have fallen behind when it comes to climate education, even as researchers show students globally are concerned about how the changing environment will impact their lives.

According to Onondaga Environmental Institute Outreach Coordinator Amy Samuels, students across the Mohawk Valley crave climate education, as well as an opportunity to be part of the solution.

In June 2020, New Jersey became the first state to mandate climate change education in schools. The modified curriculum went into effect during the 2022-23 school year, requiring K-12 public schools to integrate discussions of the environment into classes like science, social studies and even the visual and performing arts.

In January 2023, Assemblywoman Linda Resenthal, D-Manhattan, proposed a similar legislative bill (A00851) calling for New York public schools to implement climate change instruction. More than a year later the bill remains “stalled under further consideration” with the state assembly’s education committee.

“I favor a curriculum approach that is interdisciplinary, age appropriate, and available in multiple grades,” said Samuels. “Climate change is one of the most important issues of our time. Like all multifaceted problems the only way to understand and create positive change is to learn, discuss, and take action. That is the goal of these youth climate summits.”

Mohawk Valley Youth Climate Summit

The summit was held at the Howard D. Mettelman Learning Center on March 28. Local students were pulled from school to deep-dive into climate issues for the day.

The event was organized by the Onondaga Environmental Institute, with a team of partners including local teachers, the Wild Center, and the Mohawk Valley Economic Development District. Programmatic support was supplied by faculty and staff at SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Cornell University and Cornell Cooperative Extension of Oneida County.

According to Oneida-Herkimer-Madison BOCES Supervisor of Instructional Support Services Jennifer Parzych, the summit was modeled after the Wild Center’s Youth Climate Program which “aims to convene and empower young people to implement climate action plans in their schools.”

Parzych recited a quote from Nelson Mandela: “The youth of today are the leaders of tomorrow.” She highlighted that the regional BOCES program recognizes young people must be involved in building a sustainable future.

“Not only are our students the potential leaders of tomorrow, but they are the activists, scientists, influencers, and the change makers of our future,” said Parzych. “How will our students be able to change or find solutions in the future if they do not have a vast understanding of the topics and problems that our society faces? Being able to bring our students together to have discussions and listen to experts allows them to deepen their learning, make connections they may not have made before, see issues from different peoples perspectives and engineer possible solutions to issues like climate change."

Interdisciplinary approach

Attendees were given a choice of seven different seminars to choose from. Topics ranged from reducing food waste and creating food forests to tree planting and climate storytelling.

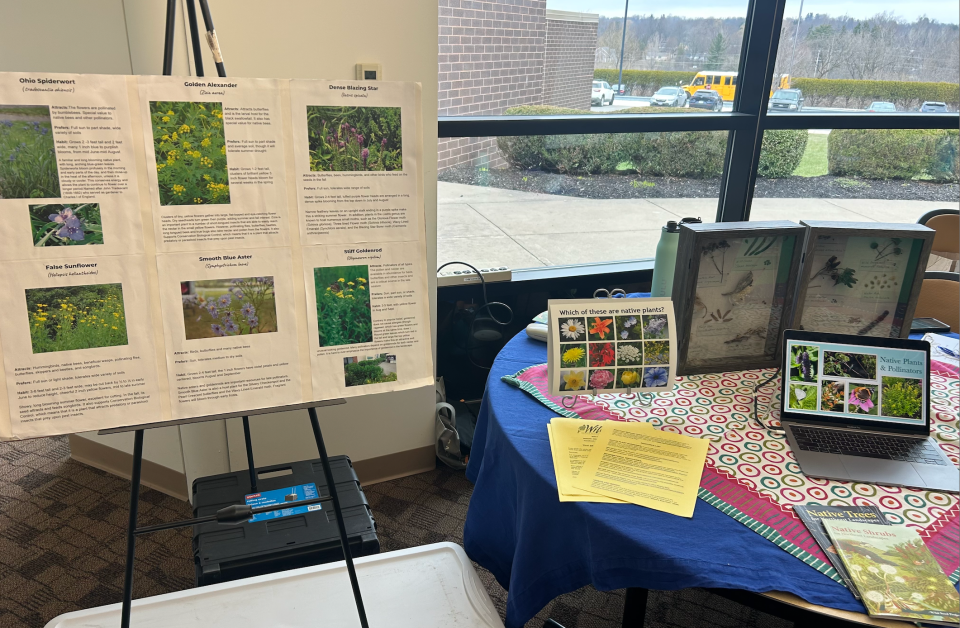

During the lunch break, students were prompted to visit the panel room featuring representatives from NYS Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA), Wild Ones, and the Finger Lakes Institute, among others.

Despite encouraged mingling, the raffle table – featuring environmental literature classics like Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer – drew a constant crowd.

“It was cool to hear from so many different perspectives,” said Carlie Lasure, a sophomore at Westmoreland public high school. “We don’t get to talk about these things much at school, aside from Earth science.”

Climate resiliency: Sauquoit Creek

Maggie Reilly, climate adaptation specialist at Ramboll engineering, led a seminar on increasing climate resiliency. She discussed her work leading the floodplain restoration program in Whitestown, while providing context on climate change and her personal experience in the environmental industry.

“I grew up at the base of the Rapid River, near the Canadian border,” Reilly recalled. “My parents had a huge garden that would sustain us and I would help them harvest. When you grow up in nature you develop a strong connection to the land and I always felt a responsibility to act as a steward.”

Reilly asked the students what it meant to be a steward of the land? A young boy raised his hand. “It means taking responsibility for the resources, like waterways, that have been given to our community and keeping them healthy,” he said.

Throughout the lecture, Reilly prompted students to relate to their experience with climate change, alluding to the lack of snow this winter, forest fires last summer, and the Dolgeville Halloween flood back in 2019.

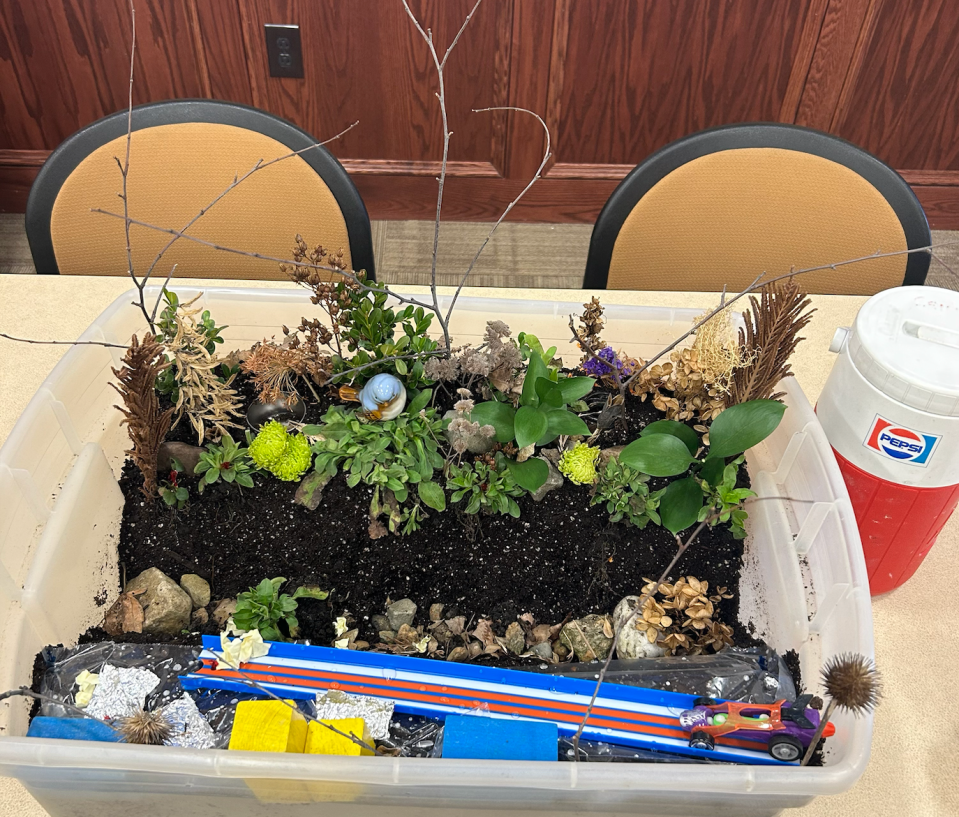

She created a diorama to help segway into discussions about water pollution, urban development, impervious surfaces, and solutions that “not only mitigate floods but help prevent them.”

One side of the box featured forested land; the other, commercial buildings. The road between the two had yellow paper to show the oil on the pavement which flows into waterways when it rains, she said.

“The saran wrap on the commercial building side shows the flat, impermeable surfaces associated with urban development,” described Reilly. “The water can’t absorb so it pools on the surface or spreads. Healthy soil in forested areas allows for infiltration; that’s the goal.”

In her presentation, Reilly spotlighted natural solutions that local engineers are using to build climate resilience: floodplain benches, native plant restoration and forest management. She pointed to the benches installed at Dunham Manor Park as a shining example.

“When we build near waterways we encroach their flow path causing them to carve deeper, instead of wider,” Reilly explained. “They have no other option but to flood. By excavating the nearby environment, to create floodplain benches, we essentially bump out the land so the river can flow the way it wants to.”

In her closing remarks Reilly urged students to get involved.

“It takes a group effort to adapt to this changing watershed,” Reilly said. “We can’t do this alone. We need all hands on deck, especially young leaders. The goal is to implement natural solutions now so we have healthy streams in the future. So nature and mankind can live peacefully together.”

Youth perspective

During lunch break, a few students offered forward thoughts on the summit. They expressed concerns on how their elders were spearheading the climate crisis.

Lauren Kulpa and Frank Calhoun, seniors at New York Mills public high school, noted some recent changes in the environment.

Frank said he likes to fish with his dad but the places they’ve been to locally, where the ecosystem is neglected, haven’t had any healthy fish. Lauren enjoys kayaking in Old Forge, but said she’s had to pick up more and more litter lately.

Both students felt discouraged that climate topics weren’t brought up in school “other than in kindergarten, when every class plants a tree for Earth Day.”

Avoiding the topic has made them feel confused; the changes around them are too large to ignore, let alone avoid in conversation.

Frank’s family usually grows a vegetable garden but said the heat last summer made that more difficult.

“This year we didn’t have much of a winter,” Lauren added. “We can see global warming is real and we want to talk about it,” she said.

A group of freshmen from Adirondack public high school – Eli Moore, Colton Underwood, and Levi Simonowski – reflected on how they felt in nature. They said it made them feel “calm and grounded.”

The boys claimed the knowledge from the summit helped them mobilize their fears into action.

“It’s scary to think we might not hear as many birds outside soon,” Eli said. “Today we learned new ways to introduce plants into concrete spaces. We want to start doing that in our courtyard at school that nobody uses.”

Carlie Lasure and Aurora Boulay, sophomores at Westmoreland public high school, took the 'Creating a Food Forest’ seminar and recounted a few takeaways.

“It was interesting to learn that U.S. agriculture is a monoculture system,” said Aurora. “We’ve been encouraged to talk with our teachers at school about creating a food forest with a variety of crops.”

Carlie said the presenter – Rebekka Henriksen, Schenectady Farm to school project manager – gardens with students and has noticed doing so creates a bond between one another and the Earth. “It was beautiful; she reminded us that nature is capable of providing all our needs,” she assured.

Aurora said she felt the food crisis was less about the climate and more about our culture.

“Everyone is so separate these days and gardening as a community could solve our social problems too,” she emphasized.

When asked whether or not they felt taken care of by their leaders they said they did not.

“The people that have the ability to change things don’t seem to have the motivation,” Aurora said. “I don’t think discussions are encouraged as much as they should be.”

After learning of the possibility for climate education Carlie smiled. She said she felt the curriculum would be “eye-opening.”

'There should be climate curriculum in local schools'

While Parzych believes there a place for a climate curriculum in local schools she directed attention to what state standards are getting right.

“Science standards lead students to discuss how what they learn impacts the world around them,” she said. “The framework addresses three dimensions of learning: asking questions and defining problems, looking at cause and effect, and analyzing and interpreting data. While a conversation that happens in these classrooms (Living Environment, Physics, Earth Science) may not be labeled "climate change" the topics that are being discussed more than likely are subtopics that fall under the umbrella.”

Each of the students interviewed at the summit only recalled climate topics brought up in Earth science, or vaguely in primary school.

Reilly praised the idea of implementing climate education across the state.

“These students are going to be the generation(s) that will be dealing with the effects of climate change,” she said. “It should be taught in school from a science standpoint. But, beyond that … climate change is affecting young people in many ways that should be discussed from many standpoints. Geography class should discuss climate migration and health class should discuss climate anxiety. Science class covers how greenhouse gasses are a result of burning fossil fuels and what climate change is doing to our biodiversity, watersheds, etc. But, we should also give the students the tools to understand what humans do that adds to climate change (land use) and what can be done to help mitigate and adapt. It needs to be addressed in schools.”

This article originally appeared on Observer-Dispatch: Mohawk Valley students long for climate education. Why is that?