After 52 years, Pensacola DIB works to sell itself to downtown property owners

As residences have slowly become the majority of properties in the Downtown Improvement Board district, its board is facing pressure to justify its existence from property owners unhappy with the organization.

The DIB was created by the Florida Legislature in 1972 to address the "commercial blight" of downtown Pensacola. The law noted that at the time, the downtown area was "plagued with vacant and deteriorating buildings which are neglected and produce a depressing atmosphere."

Fifty-two years later, downtown Pensacola is a very different place.

The boundaries of the DIB was viewed as a purely commercial center in 1972. Today, the district has 461 residential units, of which 409 are apartments. At least another 600 are in the planning stages with The Westmore development and The Heights at East Garden development.

Many of those residential units are on a single property, but even when viewed across all properties, the DIB has become a majority residential district.

In total, there are 558 individual properties in the DIB, according to data provided to the News Journal by the DIB. Of those, 223 properties have a commercial use, such as offices, restaurants, stores or hotels. At the same time, 243 properties are residential, either condominiums or apartments, and a handful of single-family homes. Of the remaining properties, 47 are parking lots, and 45 are owned by a government, religious or educational institution.

Dan Lindemann, owner of A&J Mug Shop on North Palafox Street, is one of those critics who suggested the DIB send a letter to property owners notifying them they are in the DIB. Lindemann said he believes many downtown property owners are unaware they're in the DIB.

A&J Mug Shop owner Dan Lindemann, whose shop is on North Palafox Street in the DIB, believes many downtown property owners are unaware they're in the DIB. He pushed the DIB to send a letter notifying property owners of the fact, which they did at the end of 2023.

"They don't even know they're being taxed for the DIB," Lindemann said.

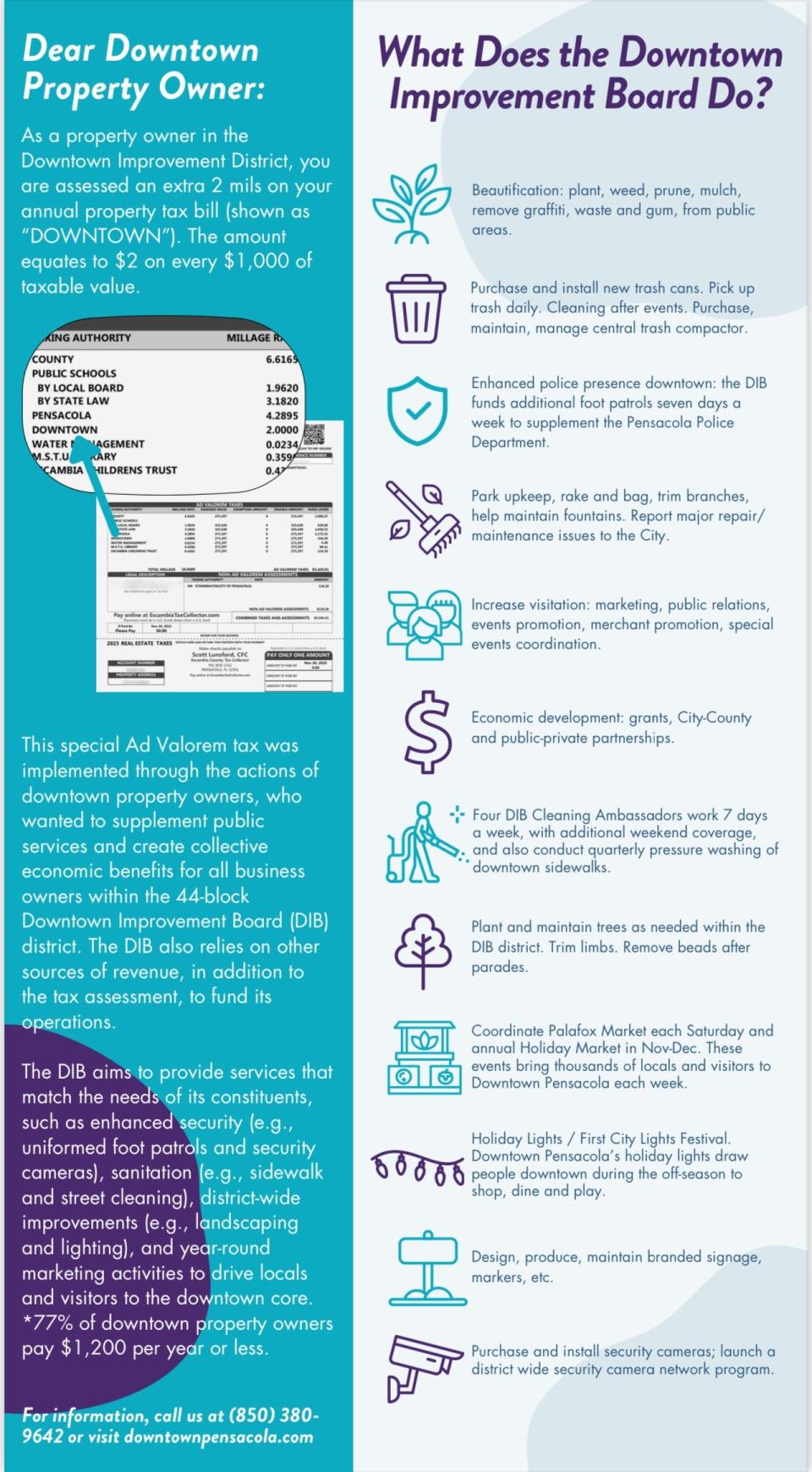

On a property tax bill or statement, the two mils in tax paid to the DIB is listed simply as "Downtown." The flier sent out to DIB property owners points out this fact.

Lindemann said that if they understood the situation, they'd agree with him that the DIB had accomplished its original mission and needed to be wound down.

"They've (the DIB) achieved their mission," Lindemann said. "Congratulations, you did a great job. Now let's move it somewhere else like Belmont-DeVilliers."

History of the DIB

The law that created the DIB required it to be approved by a referendum among property owners of the district. The law said the DIB acts as an independent corporate body and as an agency of the city. The DIB is unique as only property owners can vote in any referendum the DIB holds, such as changing its boundaries or raising the tax it levies.

The board is appointed by the mayor with City Council approval but otherwise acts independently from the city.

The law said the DIB should make plans and recommendations for the development of downtown and work to improve its attractiveness and property values, as well as acquire property to be used for public purposes downtown.

In its first decade, the DIB attempted to get a downtown mall that would cover three blocks along Palafox Street to compete with the suburban malls that were viewed as pulling away the retail business from downtown.

The plan fell apart, but other things the DIB accomplished were viewed as successes at the time, according to News Journal archives, such as a storefront façade improvement loan program for downtown businesses and using funds to build or expand downtown sidewalks. In the 1980s, the city created its CRA, and the mission of the DIB shifted to promoting downtown businesses and recruiting more businesses to downtown.

In 1986, property owners in the DIB voted to approve a tax increase from one mill to two mills that would be used for the promotion of the downtown district, according to News Journal archives.

The DIB was now responsible for promoting and marketing downtown, organizing festivals, and paying to put up holiday lights each year with the extra tax revenue.

For every mill of property tax, a property owner pays $1 in taxes for every $1,000 of value assessed on their property.

The second mill came with a stipulation that it had to be reaffirmed by DIB property owners every five years. DIB property owners approved it again in 1991 but rejected the tax in 1996. The failure was blamed on the confusing voting process, which allowed more votes to go to property owners with higher-valued land.

In 1997, the second mill was reinstated but then rejected again in 2002. In 2003, the law changed to give every property owner a single vote, and the tax was passed again without the requirement to renew every five years.

The vote in 2003 was the last time downtown property owners voted on any DIB measure. There was an attempt to expand the DIB's boundaries in 2006 that would've required a vote by all property owners being included in the DIB, but that measure was killed by the City Council by one vote.

In 2008, the DIB's mission was further expanded when the city gave it the responsibility of managing all downtown parking. The city took back parking in 2020 after the disastrous roll-out of a parking app in 2018, and legal questions arose over the DIB managing parking outside its 44-block boundary.

DIB's role today

Pensacola Mayor D.C. Reeves said he feels the DIB still serves an important role in the city.

"As someone that was part of the DIB and paid the millage as a business owner, I think there's value in having some representation for that investment in the city," Reeves said. "And when you're a city and a county, it's hard to have a hyper-focus on an area that, economically speaking, generates a lot for us − not just in property tax."

Reeves said in the city's most recent survey of residents, 68% viewed the downtown area as a crucial driver of the local economy.

"It's not just folks that live downtown or work downtown who understand the value of downtown," Reeves said. "So for the DIB members that are paying taxes, and to have that representation, I think that that does create value."

Lindemann doesn’t believe people are aware of the DIB, and it should do more to communicate with property owners about how it spends their tax dollars.

"It's another layer of our city (government) that we don't need," Lindemann said. "Again, that's just me. I don't understand why we have all this stuff, and I may be totally wrong."

Downtown businessman Ed Carson served on the DIB in the 2000s, but agrees with Lindemann it outlived its purpose.

"If I'm going to spend two mils, I'd rather see it spent on stormwater treatment or some other thing," Carson said. "I know it's a totally different funding bucket. But I just don't see a real need for a DIB anymore."

DIB Executive Director Walker Wilson said there's no question the original goal of not having a vacant downtown has been achieved, but the DIB still has a role to play in improving the city.

"The main thing that we see ourselves here to do is to make sure that downtown is clean and safe and that we can help promote these businesses to be as successful as they can," Walker said. "And I think we do a good job with that. I certainly think there is a role for the DIB still in this community."

Walker said he's heard the criticism from Lindemann, and it was those comments that motivated the DIB to send out mailers to property owners on what the DIB is doing today.

The mailer also asked downtown business owners to take a survey on their opinions of the DIB. So far, Wilson said no property owner has responded to the survey.

Beautification, sanitation, enhanced police presence, park upkeep, downtown marketing, economic development, four full-time "DIB cleaning ambassadors," the Palafox Market, downtown holiday lights, branded signage, and soon the purchase of public security cameras are all listed as things the DIB is doing today.

Along with the marketing activities the DIB does for downtown businesses, every day DIB staff are doing things like picking up trash and removing graffiti downtown that the city would otherwise be paying for, Walker said.

Walker said almost every major American city has an organization like the DIB. While some are privately funded and some only tax commercial properties, the DIB is needed in a downtown business area.

"I think the services that we provide and that the DIB taxpayers provide are certainly needed because if it goes away, I don't know who's going to pick up those services," Walker said.

This article originally appeared on Pensacola News Journal: Pensacola DIB works to sell itself to downtown property owners