18 Sensible Questions About Coronavirus, Answered Sensibly By An Actual Doctor

The mounting spread of the coronavirus, now known as COVID-19 has prompted widespread concern around the world as public health officials race to contain the outbreak. The novel coronavirus has killed more than 2,800 people worldwide, with the vast majority of deaths occurring in mainland China. However, over 83,000 cases have been reported, on every continent except for Antarctica. The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared a global health emergency.

In an effort to address the wide number of concerns and misconceptions in regards to this developing situation, Dr Keith Roach – an internist at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital – has shed some light on the most pressing concerns. Dr Roach answered questions about the coronavirus submitted by Hearst employees. The following is a summary of that conversation.

How can we put the coronavirus outbreak into context with other high-profile outbreaks in the last decade, like Zika or H1N1?

Zika isn’t a good comparison, because Zika is spread by mosquito bites, and COVID-19 is spread person-to-person, having first been introduced to humans through an animal (COVID-19 is very closely related to a bat coronavirus, but whether it went through another animal first is not known).

The infectivity of an infection is described by a number called the basic reproductive number, R0, (we say “R nought”). The best estimate for COVID-19 is that the R0 is about 2.2, meaning it is roughly as infectious as influenza or SARS. However, the R0 doesn’t tell you all there is to know about how alarming the infection will be: SARS infected 8,000 people or so, while there have been 30 to 40 million cases of influenza in the US this season. It seems to be similar to H1N1 influenza, but unlike influenza, nobody is likely to have partial immunity, such as might have been built up by previous infection or immunisation to flu. COVID-19 is just too new.

How does the mortality rate compare to the flu?

The best data comes from China from just last week: of over 44,000 confirmed cases, 2.3% of people died. The case fatality rate is strongly linked to age, with older people being at a much higher risk of death.

In a typical flu season, the case fatality rate is about 0.1%. In 1918, where the H1N1 influenza killed 50 million people, the case-fatality rate was 2.5%. The possibility of a worst-case scenario of coronavirus not being contained, and being as infectious and deadly as the 1918 influenza virus, is what keeps public health officials up at night worrying.

What precautions should we be taking when riding any public transportation services? How long does the virus linger on porous/non-porous surfaces?

Although there are not data for COVID-19, other coronaviruses have been shown to persist as long as nine days on glass, metal, or plastic in the worst case, with a very large amount of virus inoculated. Packaged goods from China are very unlikely to have infectious particles due to long shipping times and reduced virus infectivity on paper.

COVID-19 can be spread from infected surfaces, so keeping hands washed (or frequently using alcohol-based sanitiser) and being careful not to put your hands to your face will help reduce infection. However, the major risk is person-to-person through droplets from a cough or sneeze.

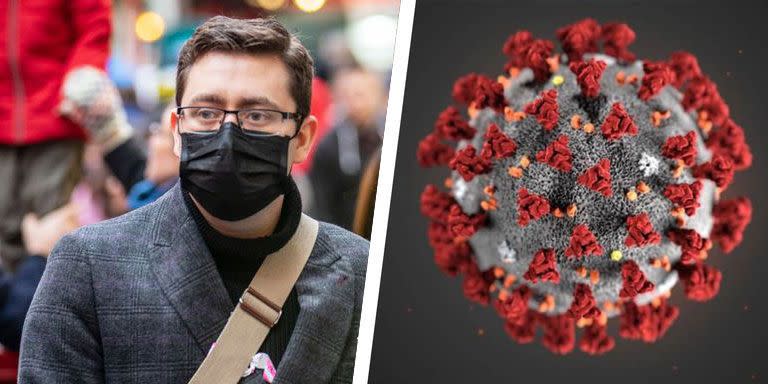

What's your advice for wearing a mask? Should masks be worn if traveling on a plane?

The CDC doesn’t recommend masks for walking around outside. Masks are appropriate for clinicians taking care of known cases. The correct mask for clinical care is an N-95 respirator, which needs to be fitted properly to the face. If the mask doesn’t fit well, it can lead you to think you are protected when you are not, and might actually increase your risk of getting infected. They are also quite unpleasant to wear for any length of time at all, if they fit correctly. Finally, you can contaminate yourself taking it off if you aren’t trained to do that properly.

Fabric masks probably do very little except protect you from splashes, but even so the holes in the fabric allow the viruses to pass right through. Surgical face masks are designed mostly to protect the patient from the wearer. It keeps your coughing and sneezing droplets from getting out.

In terms of air travel, a study found people sitting in window seats are the least likely to be exposed to viruses.

Were the isolation efforts that China made necessary to the coronavirus's containment?

Absolutely. In an infectious epidemic, the public health officials have only a few really effective tools. One is an effective vaccine, which there is not yet available for COVID-19. Another is medication, if there were effective antiviral medicines, which there aren’t any proven (trials are ongoing). The final, and oldest, is keeping people away from each other, especially quarantine and isolation. In China, the methods used were intensive: important gatherings were cancelled, and travel was highly restricted. A city of 11 million people was entirely quarantined.

Since the number of cases in China has plateaued, are we perhaps on the downward curve of the spread?

That seems to be the case in China, but the news from Italy is disturbing, and many European countries are reporting coronavirus. Because 80-90 per cent of cases have no or minimal symptoms, many public health officials fear that the opportunity to contain the virus is lost and a pandemic is inevitable.

If I recently traveled to Milan and have children at home, should I be worried about exposing them?

In absence of symptoms, it is possible but unlikely you are capable of transmitting the virus. There has been documented person-to-person transmission in Milan, but only a handful of cases.

People who are sick are much more likely to transmit the disease than people who are asymptomatic or have minimal symptoms. If you had fever or cough, that should be evaluated, and you should call your doctor for guidance.

Is there anything we should be doing to prepare ourselves?

The most important precaution is to not get sick: wash hands religiously (or maybe obsessively); keep away from people who are sick (literally six feet away will eliminate most risk); try not to touch your face; if you are sick, STAY HOME.

Should we stock up on vitamins or are there any medications we should have on hand?

As we have seen from the experience in China, it is possible that there may be interruptions to the supply of food and other goods. However, hoarding and panic buying is a very bad idea. Building up a two week supply of non-perishable foods for your family makes sense. Think also about medications, food for your pets, batteries, etc.

Are there any differentiating signs of contraction we can watch out for early on?

No, coronavirus can start exactly like a cold. Symptoms typically begin about five days after exposure, but the incubation period could be as long as 14 days. As noted before, many cases have no symptoms.

Symptoms of severe disease are fever, cough, and shortness of breath. This could indicate pneumonia, the most dangerous form of the disease, and the one most likely to lead to requiring hospitalisation. Critical illness with COVID-19, especially in the elderly, is very dangerous.

If we feel a cold coming on, is it recommended to immediately go to the emergency room?

No! Call your doctor. The same is true if you have no symptoms but are exposed to a known contact. We don’t want potentially infectious people coming into the medical system and potentially infecting people there, who may be at very high risk due to age or medical condition.

If you have what seems like a cold and no known risk, you probably don’t need to see the doctor anyway. Of course, if you are really sick, you need to get an evaluation. This advice is likely to change in the event of a major pandemic.

I'm pregnant. Should I be taking any special precautions or preventative measures at home or at work?

No, pregnant women should take the same precautions as anyone else. There are case reports of 18 pregnant women with suspected or confirmed COVID-19: none of the babies developed any symptoms of the virus. However, similar viruses can be more severe in pregnancy so your doctor will take extra care of you in the unlikely case you get sick.

Does the virus stay active forever or do we need a vaccine in order to be "cured"?

People only stay in the hospital if there are treatments we can do there we can’t do at home, or if they are so sick they need intensive monitoring. That’s true in any situation. Hospitals have efficient isolation rooms to keep other patients safe and trained personnel to keep themselves safe.

Once a person recovers from coronavirus (98 per cent do), they are likely to have lifelong immunity, if COVID-19 behaves the way other coronaviruses do. Even people with minimal or no symptoms will likely develop immunity. An effective vaccine would provide protection without getting ill.

What’s happening with a coronavirus vaccine?

Normally, a vaccine takes a minimum of three to five years to develop and test. In theory, a vaccine could be developed for COVID-19 in 18 months, which would have to be some kind of record.

Is there a possibility of a vaccine being developed in time to help the current situation?

No chance. None. Sorry.

Vaccine safety is so important. Back in 1976, they rushed out a swine flu vaccine – and it was a bad vaccine. There are still patients who refuse flu vaccines because of episodes like that.

What classifies as someone who had coronavirus as "recovered"? Are they still contagious?

This isn’t really known. Right now, the CDC is recommending keeping people in isolation until their testing becomes negative two days in a row. Most likely, people will be sent home for some period of time after that to be extra-safe.

How should people be thinking about upcoming travel out of the country?

Many doctors who are risk-averse would recommend that you probably should cancel your travel plans. The immediate future even over the next few days is unknown: what things will be like in two weeks is anyone’s guess. Areas that aren’t affected now may report being affected while you're reading this article. There is a good chance that tourist destinations in affected areas will be closed, and that quarantine may be required upon return, especially if the CDC upgrades the severity of the affected area. You may have the time of your life and be able to see things with nobody there. But it might also be the disaster vacation from hell.

What would be your general advice for how we should be feeling at this point?

Between slightly and moderately anxious. We have prepared for disaster before and it hasn't really shown up. Prepare for the worst: hope for the best.

You Might Also Like