You're *Not* Doomed If You Are Genetically Predisposed To Weight Gain

Adriana Romero-Olivares signed up for 23andMe about seven years ago because she was curious about her ancestry. But the DNA testing company sends updated reports to its customers as it develops them, so in 2018, Adriana received an email notifying her that she had a new report available: a Genetic Weight report. She clicked, and it told her, "Adriana, your genes predispose you to weigh about 9 percent more than average."

Learning that info was a strange pill for her to swallow. "I’ve struggled with my weight my entire life," says Adriana, 35. "When I got the results, I felt validated, but then at the same time, I felt upset, because I struggle to accept the fact that I just can't be thin."

Over the past few years, DNA testing companies have started churning out reports like that one that specifically tell someone their likelihood of becoming overweight or obese. The thing is, getting bold text in your inbox that says you have a higher propensity to gain weight than the other people in your HIIT class can feel like a bit of a bomb, as Adriana points out.

So how reliable are these reports—and can they actually aid your efforts if you're trying to lose weight? Here’s what experts have to say.

For starters, experts know that your genes affect your weight, but it’s unclear just how much.

"Just from pure observation, you can tell that there's a genetic component because you can look at families and see that weight gain runs in families," says Rachel Mills, a certified genetic counselor and assistant professor in the University of North Carolina-Greensboro Genetic Counseling Program. Beyond that, it gets more complicated.

Researchers don't have a firm answer in terms of to what degree being medically overweight or obese is influenced by genetics, compared to lifestyle and environmental factors. They've estimated that anywhere from 40 to 70 percent of person-to-person variability in body mass index (BMI) is due to genetic factors. (Obvious alert: That's a wide range.)

And while researchers have already discovered hundreds of genetic variants associated with BMI, "we've only got a partial picture of the genetic component so far," says Struan F.A. Grant, PhD, director of the Center for Spatial and Functional Genomics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Grant notes that BMI is a very polygenic trait, "which means there are many, many genetic factors contributing to the trait," he explains. Each genetic variant could have a somewhat different effect on BMI, too—that’s something experts are still figuring out.

So what does it mean if a person has several genetic variants associated with obesity? Once we have a more complete picture of how genes drive obesity risk, we could eventually be able to get data (say, from our doctor) that helps guide how we approach weight management on a personal level, Grant says. But right now, all we definitely know is that certain genetic variants are more common in obese people compared to non-obese people.

23andMe's Genetic Weight reports even explain right under your results that your predisposition doesn’t mean you definitely will weigh more or less than average. 23andMe senior product scientist Alisa Lehman says that, in 23andMe’s model, "the genetic component [accounts for] less than 10 percent of what the total difference in weight between any two people is." The company does extensive user testing before releasing reports that delve into new areas, she says. And, in this case, they wanted to make sure that customers have a understanding understanding that genes are only one factor in weight management.

All of this means that there are definitely some limitations to weight-related DNA testing.

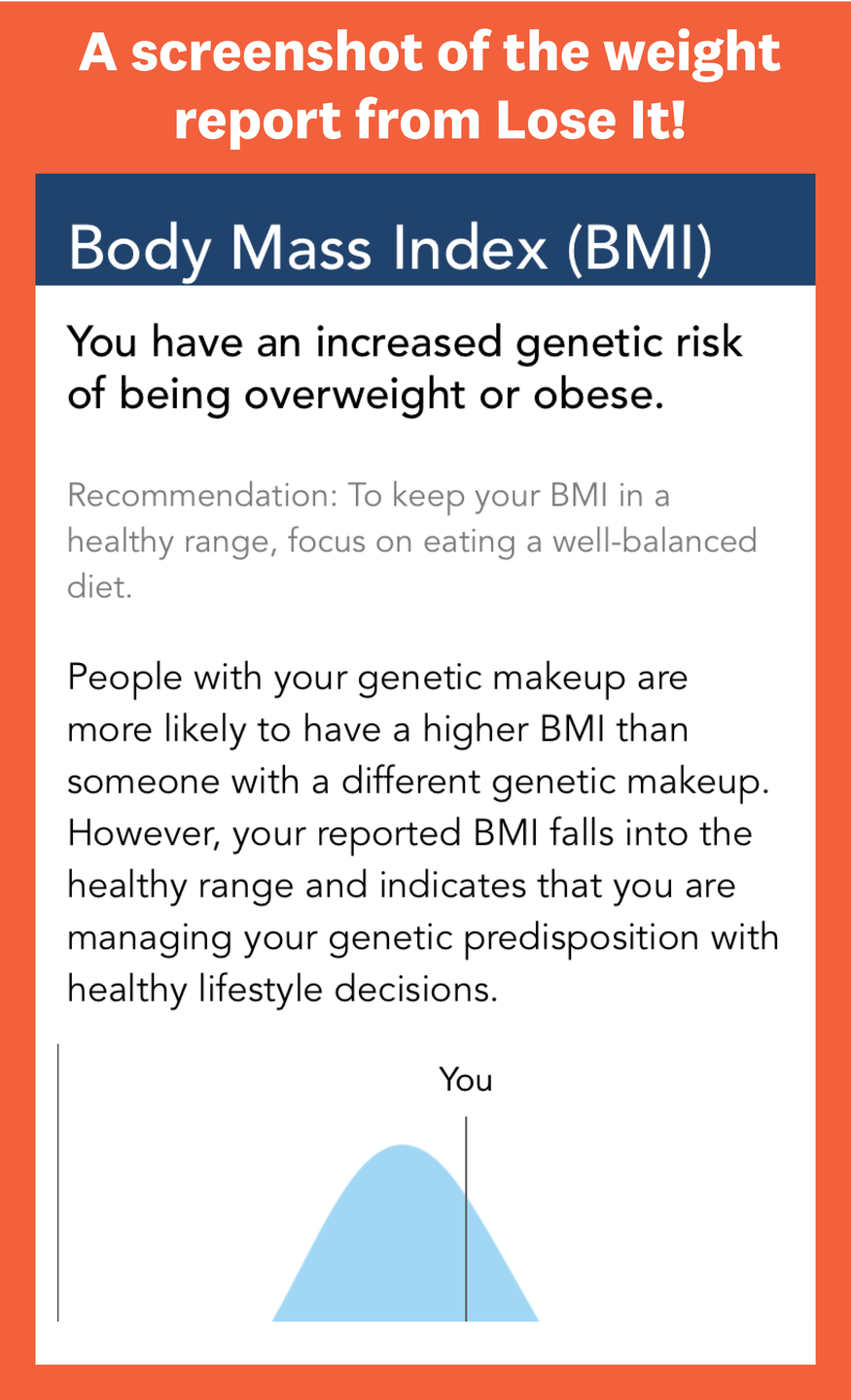

How businesses gather weight predisposition info varies company to company. For example, health-focused DNA testing and supplement company Vitagene and weight-loss platform Lose It! use results from other institutions’ research papers to internally calculate a person’s risk of becoming overweight. (Lose It! also asks you to input your AncestryDNA or 23andMe raw DNA files—the company doesn’t do its own DNA testing.)

But 23andMe, arguably the most well-known service, uses its own data to come up with a person’s weight predisposition. "We have a research program that allows people to answer questions and then, from that, if they opt in, we can use their data to make new genetic discoveries," Lehman explains.

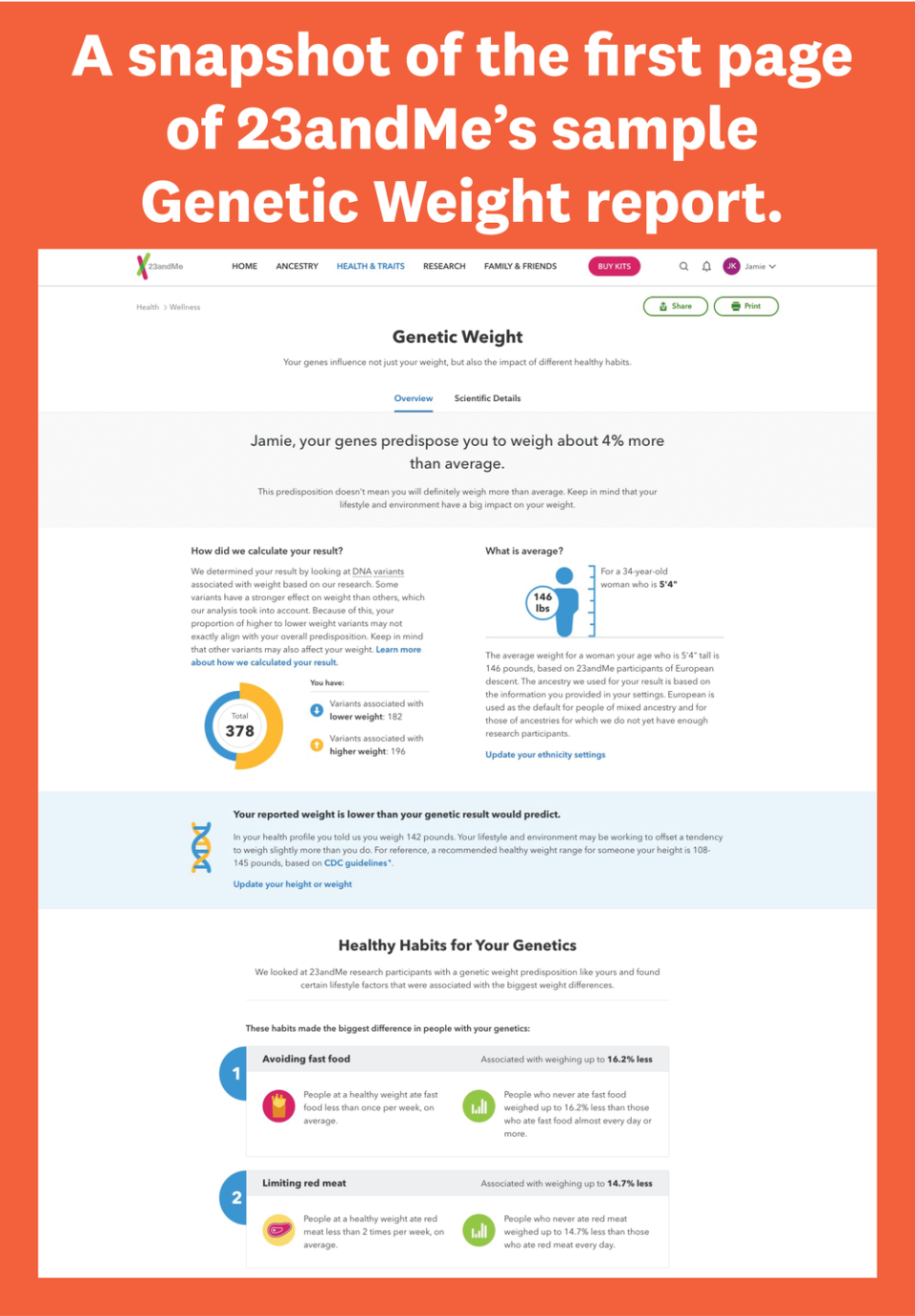

23andMe researchers released the Genetic Weight report in March 2017. They created it by looking at data from more than 600,000 research participants, including their DNA and self-reported height and weight. (Check out a sample report here.)

23andMe researchers found 381 variants associated with BMI, and used that info to create a modeling process that weighs certain variants more strongly than others and considers age, sex, and ancestry to determine the result they send to a consumer. "So when people provide us their saliva sample and we gather their DNA, we can look at those 381 places and say, 'Hey, okay, you have some variants that increase your predisposition and some variants that decrease your predisposition, and the magnitude of each of those variants differ a little bit,'" explains Lehman. "But we add up the effect of all of that to get a sense of whether your predisposition is to [weigh] a little bit more or a little bit less than average."

Depending on your ethnicity, there might also be another caveat. The largest population that 23andMe has data for is people of European descent, so researchers were only able to look at genetic and BMI data from people of European descent to identify the weight-related genetic variants and their effects. Then they looked at how well that model worked for people of other ethnicities, tweaking the model as necessary. Therefore, people who have Latino, African American, East Asian, and South Asian ancestry can get results that are somewhat customized to their ancestry, while people of mixed ancestry or other ancestries default to European. (This Eurocentric bias comes up in a *lot* of research that scan people’s genomes for genetic variants associated with a disease or trait, not just in relation to BMI.)

There's also no proof that these weight reports help people successfully lose weight.

It doesn’t appear that any companies that provide weight-related DNA results have conducted any formal research on how the info impacts people’s weight-loss efforts. Lehman says 23andMe has looked "a little bit" into whether the information in the Genetic Weight report has actually helped consumers with weight loss or management, but that they haven’t come up with anything "publication-worthy," adding that it’s challenging to untangle this report from other info the company provides on nutrition and exercise.

23andMe also hasn’t taken a fresh look at their Genetic Weight report model since releasing it, but it plans to. "We do periodically review all of the reports that we have, and Genetic Weight is coming up for that periodic review, so we will soon review it and see if any updates are warranted," Lehman says.

Learning bummer info about your weight predisposition could negatively impact your mindset, though.

Of course, some people might just like or even be motivated by having more information about themselves, and that’s totally fair. But here’s an interesting twist: A recent study out of Stanford University found that just knowing your genetic risk for obesity can impact the way you respond to food.

In one of two experiments, participants ate a meal and then, on a different day, ate another after hearing that they did or didn't have a high-risk genetic variant associated with obesity and lower satiety. Here’s the catch: Researchers chose randomly whether participants would be told they had the genetic variant. (The researchers fully debriefed the participants about their actual genetic risk only about an hour later, while they were still under clinical supervision.)

"We saw that the information we gave to people was like a self-fulfilling prophecy," says Brad Turnwald, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow in the department of psychology at Stanford University and lead author of the study. When researchers told people they didn’t have an increased risk, they reported feeling full faster and even produced more of a fullness hormone. "Overall, what we saw was that what people thought had as much of an impact, and in some cases a greater impact, than what people's actual gene sequence was," Turnwald says.

The takeaway, says Turnwald, is that we need to better understand the psychological impact of these kinds of DNA test products. "We're definitely not trying to say that genes don't matter at all. There are some diseases for which they really are predictive," he says. "But for the majority of things like weight loss and how hungry we are and how well we exercise—things for which people are looking for explanations that they just weren't made to run or they just don't feel full based on their genes—the story is not going to be that simple."

Essentially, we’re a long way away from knowing what a genetic predisposition to weight gain really means. In the meantime, your own healthy habits still make a big impact.

Mills doesn’t believe that it’s possible for any sort of calculation to exist at the moment that can accurately analyze a person’s propensity to gain weight. If someone told her they were interested in one of these reports, she would ask them to "think seriously about how you would use that information," Mills says.

"I know, for me personally, I would see a report [that says I can’t lose weight as well through diet and exercise] and maybe throw up my hands and be like, 'Well, I'm just going to go to McDonald's because it doesn't matter—no diet and exercise is ever going to help me lose weight, so why do I need to even try?'" she continues. "And that can have a really detrimental effect."

If someone has already received genetic weight report results and asked her how to interpret them—or wants to know how damning they actually are, so to speak—Mills would emphasize this: "Genetics is just one piece of the big picture," she says. "Just because this genetic report says that you are less likely to lose weight, that is not an absolute."

Adriana is Mexican, and she’s also a scientist, so she knows that she should take her reported propensity to be overweight with a grain of salt. She says her Genetic Weight report is one piece of information, "an indicator that I tend maybe to gain weight or that my metabolism is not as fast as the average person’s," she says. But she’s not going to make major lifestyle changes based on it.

Over time, though, the report has had a positive effect on Adriana’s mindset: "The way that I think about it now is, if I'm predisposed to weigh a little bit more than the average person, then I might as well just exercise and have a balanced diet for the sake of health and not necessarily for the sake of losing weight, which, for a very long time, was the main focus for me."

You Might Also Like