Was This Yosemite’s Most Miserable Shiver Bivy?

This article originally appeared on Climbing

This feature first appeared in Climbing's 120th issue (summer 1990) under the title "A Turn of the Cards." We've migrated it from the archive to the internet in order to celebrate the life of Yosemite legend Mike Corbett, who passed away on May 8th at the age of 68. During Corbett's long career as a Yosemite climber, he helped dozens of climbers--including Mark Wellman during his first paraplegic ascent, and Jim Bridwell on his final jaunt up the Big Stone--achieve their dream of climbing El Cap.

But Corbett was also, as John Middendorf's iconic story relates, a participant in one of the most miserable-sounding big wall epics in Yosemite history.

We suggest you read on.

--The Editors

It was early spring 1986, Camp Four parking lot, Yosemite Valley.

"So what have you got in mind, Bob?" I asked my friend, who'd just showed up in the Valley.

In his usual soft voice--his sentences tend to trail off at their ends--Bob said, "I want to try soloing The Prow."

Fresh in my mind was the memory of a recent rescue on The Prow (V 5.10a A3), a classic aid line on the east face of Washington Column. During it I had been given the honor of lowering down to the climbers, one of whom happened to be a good friend, then jumaring back up with them.

I gave Bob a sideways look. In my two-and-a-half-year tenure as a member of the Yosemite Search and Rescue team, I had been involved with dozens of lift-offs, and I was both smug and quick to dole out patronizing advice. "Just don't get rescued," I said flatly.

Bob looked nonplussed, but before he had time to think, asked, "Why?" Because, I thought, rescues are serious undertakings, and getting rescued doesn't do a thing for your reputation with the Valley denizens, much of whose inner language centers around such events. "Rescue bait," they call certain less-promising big wall climbers. All I said was, "I don't know, that's just the way it is around here."

*

Several weeks later, two of my rescue-team friends and I would start up the South Face of Half Dome, intending to make a winter ascent.

The South Face of Half Dome, one of Warren Harding's finest masterpieces, is a 2,000-foot wall. Its upper half is a blank sea of white granite, void of any apparent climbable features. Remote and beautiful, the route has a history of failures, although Walt Shipley's extraordinary solo ascent two years ago and the nearby free line put up recently by Dave Schultz and Scott Cosgrove seem to have tamed the wall's fearsome reputation. On the 1968 first-ascent attempt, Warren Harding and Galen Rowell were trapped by a severe storm for several days and had to be rescued, which in itself was a pioneering event in technical extrication, because at that time big wall rescue technique was still in its infancy. (The rescue was documented in The Vertical World of Yosemite.)

Other parties had faltered as well, for reasons ranging from lack of proper hooking gear to debilitating heat, often necessitating retreat. In several cases, friends on the summit have lowered ropes, gear, and provisions to stranded or stalled climbers.

In fact, the South Face had hosted more failures than successes when my eventual partners, two Yosemite regulars, Mike Corbett and Steve Bosque, decided to go for a winter ascent. The season had been extremely mild--some called it a drought winter--so the venture seemed very feasible.

Yet from the onset of preparation, as the two made multiple six-mile uphill plods to Half Dome's base, and then fixed several pitches, they experienced setbacks. In one storm snow sloughed down the face into a 30-foot pile on the ground, forcing Steve and Mike to spend an entire day digging out their gear. Then it took another month before the long-term weather report looked good.

Normally two climbers make for the most efficient wall team, but Mike and Steve, sharing a feeling of burnout, asked me to join them. Mike and I had done a few big walls together in the past, and I always found myself charged up by his undying affinity for them. Steve's deliberate and understated approach to such adventures, which he would regularly squeeze in between periods of raising a family and working full time, always seemed impressive to me. I was really excited about our team and the chosen route. It was going to be my 40th long route (1,000-plus feet) in Yosemite.

Shunning the more intelligent option of packing two separate loads to the base, I carried all my gear in a single towering 100-plus pound haul bag, while Steve and Mike carried their light final assault loads. By the time we got up the Vernal Falls switchbacks--only two miles into the eight-mile approach--I was staggering every step. The one-shot technique works well for El Cap where the torment of the approach is halfway five minutes after you step out of your car, but this was one long, steep uphill plod. Mike and Steve periodically tried to persuade me to off some weight onto them. With too much pride in self-sufficiency, I refused. Thirty-one thousand staggers later, the grueling approach ended.

That night, it sprinkled on us, but the next day we climbed in beautiful sunny weather. The first two days took us to the end of the Arch, a huge left-facing dihedral soaring halfway up the wall, and onto the Face, a thousand feet of 75- to 80-degree featured rock with very few cracks.

The eighth pitch, which we named "The Great Escape Hatch," was a contortionist's dream: a gaping Bombay chimney, awkward as hell, like an aid version of the Harding Slot on Astroman. After that pitch, I told Mike, "You know, regardless of a wall's actual rating, every route seems to require the sum total of my aid experience." Mike understood exactly.

The third day, in T-shirts, we climbed five of the 11 remaining pitches. I eyeballed each for its free-climbing potential, realizing that we just might have discovered the most awesome free-climbable face in the Valley. I free climbed between some bat-hooking sections on my leads just to try it out. (Bat-hooking--placing specially designed hooks in shallow drilled holes--is a technique invented by Harding in order to surmount blank sections of rock.)

Up to this point the climbing and setting had been awesome, and we often commented on what an ultimate gem of a route this was. We were having a great time.

The day's fourth pitch took us to one of the Tri-Clops, three large, shallow, dark indentations in the rock that from the ground look like caves and, with some imagination, passageways into the depths of Half Dome. This evil-looking place had been Harding and Rowell's demise, and the energy of their desperation seemed to still linger. Though dusk was fast approaching, Mike had an uneasy sixth sense about the spot and decided to go for the next pitch, a steep bat-hooking stretch that ended on The Ledge, which on the topo looked like it might make a good bivy.

Darkness set in midway through Mike's lead. Then came the frightening clanging of gear and yank on the belay rope. Dead silence. "Hey Mike, you OK?" Silence. "Hey, Corbett!"

Steve and I flashed headlamps upward but all we could see was the rope disappearing into the darkness. Then from above came the explanation. Mike had popped a bat-hook and taken a 20- or 30-foot fall, fracturing his finger in an attempt to grab the previous bat-hook. But a broken finger barely slows down a guy like Mike, and he finished the lead. We set up the bivy in darkness at The Ledge, which turned out to be nothing more than a small six-inch stance formed by a protruding flake.

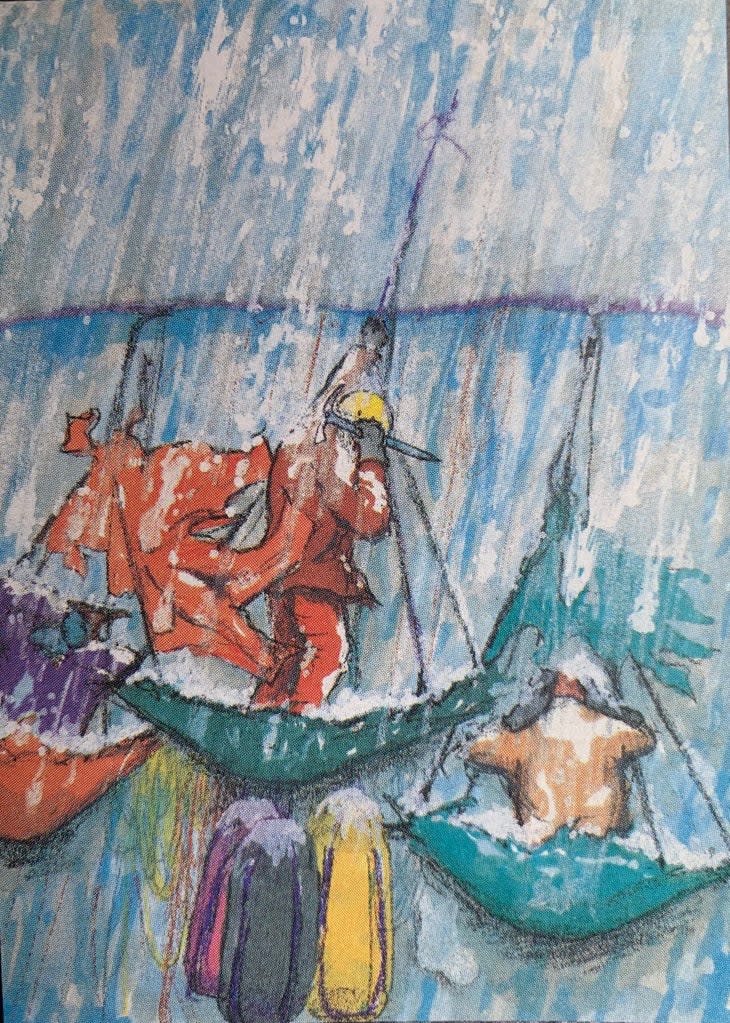

Sometime in the early hours of Friday morning, clouds moved in and a light rain prompted us to dig out our portaledge rainflies. Little did we know it was the start of one of Yosemite's worst storms ever. At dawn it was still pattering steadily. Mike suggested a general rest day, and Steve and I agreed. But instead of clearing, which our little box radio had promised, the weather became worse. We braced ourselves for a storm. Later, when the completeness of the radio's lie became evident, I would jettison it, as a symbolic gesture of our isolation.

On Friday evening the rain became a torrent and the winds picked up. Sometime that night, Steve's ledge collapsed, and in the minutes it took him to reconstruct it he got completely soaked. From the relative comfort of my slightly damp ledge, I listened to his struggling and cursing and felt sorry for him, but there was nothing I could do, aside from lending him my headlamp, since an exit from the ledge for even a minute meant complete saturation. It's funny about Steve; even when he has good reason to curse, he does so only as if playing a part--no semblance of actual anger exists in his tone. He is always like that.

Hours later, I felt my ledge's suspension straps begin to slip due to the wet and icy conditions. I knew what was happening: slowly, my ledge was being twisted, one outside corner sliding down, and the other twisting up. As if it were trying to dump me out into the void. Any movement accelerated the slippage, but in the dark I could not see what to do to fix it. Trying not even to breathe, I cried, "Steve, I need my headlamp back, NOW!" (In the adverse conditions my headlamp, a Petzl Zoom, was our only functioning piece of gear, and it had become a coveted item.) But in the twisted tangle of his nearly destroyed portaledge, Steve was forced into stillness; even the slightest wiggle caused his ledge's suspension to slip, then the ledge to fall apart (by this time it had collapsed several times.) He tried to extend the headlamp to me, but to no avail.

So I tried to re-tension the suspension without light. My movement caused the structure to slip completely. The end-tubes dropped out of their shallow side pockets, leaving me hanging in space among an untenable assortment of tubing and fabric. Instantly, everything became soaked, as if I had jumped into the Merced River in full regalia--except that this was colder. From the haul bag I dug out my spare wool clothes and rain gear, but in the deluge they were soon drenched, too. A foot-thick sheet of water poured down from the moderately angled face above. Rain pelted us, driven sideways by the high winds. I finally retrieved my headlamp, and, with a mixture of determination and resignation, took my time reassembling the ledge. I couldn't get any wetter.

In the end the failing portaledges didn't matter, because by morning all of us were soaked to the bone anyway. Seemingly by osmosis, moisture poured through my "waterproof" ripstop rain fly. The waterproof coating mysteriously fell off the fabric in large cobweb-like stick sheets, creating another mini-storm inside.

By 10 a.m. Saturday the winds were blowing over 50 miles per hour, with gusts throwing us and the ledges about. Visibility was nil. Then the temperature dropped, the rain turned to icy BBs, and our soaked gear began to freeze solid.

"We're gonna die in these conditions," Steve said. "We've got to at least try to get out of here!" We exited our ledges and inspected each other and our gear. Instantly, fingers and toes went completely numb, and the wind and cold penetrated to the bone.

With uncanny foresight, Mike had insisted on leaving a rope fixed over the otherwise-irreversible roof below the eighth pitch. Still, that was five rappels down and several hundred feet to the left. As we discussed our situation we noticed that the ropes in front of us were frozen to the wall in solid tangles, and would need to be chopped out with an ice tool. We quickly realized that to retrieve even a short length of usable rope would be impossible. Even if we could have, our jumars would never have grabbed on the frozen cord, the ice-covered wall would have thwarted any effort to swing sideways to belay anchors, and a near-certain hang-up in the rappels would have resulted in a fatal separation from each other. Drilling our own anchors was out of the question, as it would require far more manual dexterity than our frozen fingers could provide. And in the back of my mind I remembered how miserably Rowell fared in 1968 while attempting to rappel in similar conditions from just 100 feet below our position.

All sorts of potential and likely nightmares crossed my mind, each ending with three bodies frozen to the wall. I was the first to disappear back into my portaledge.

We remained as a team, huddled in place, waiting.

All Saturday the storm beat us in a deafening roar of flapping nylon and typhoon winds. I realized how much my entire life depended on my lightweight rain fly. Violently whipping, it seemed ready to rip to shreds any minute. Earlier, Steve's fly had been torn apart, and critical corner parts of his ledge were mangled into scrap metal, rendering it useless. He was now sharing Mike's portaledge. If either of our two remaining ledges or flies failed, somebody was bound to die from exposure.

In the meantime, unbeknownst to us, a rescue effort was underway down below. In the deepening snow, Werner Braun, Dan McDiver, Sue Bonovich, and Tracy Dorton had hiked up the five miles to Lost Lake, from which they could get the Valley's closest view of the South Face, and were trying to communicate with us through a bullhorn.

In one of the infrequent lulls in the storm, we suddenly became alert, hearing muffled noise. Instinctively we broke out in loud shouts to expose our position. WE were able to distinguish from below, "Do you need a rescue?" WE looked at each other, quickly decided that we were in dire straits, and yelled in unison for help until we were hoarse. We couldn't see who we were calling to.

Like turtles, we then retracted back into our shelters. As the hours passed, the initial hope and excitement of possible help dwindled and was replaced by renewed concentration on survival. We knew the top of Half Dome would be inaccessible: the hiking-route cables were buried and frozen over, and the storm would prohibit climbing to the top. The uncertainty of our fate made our exhausting, freezing misery that much harder. Right now, the flames of hell didn't seem so bad.

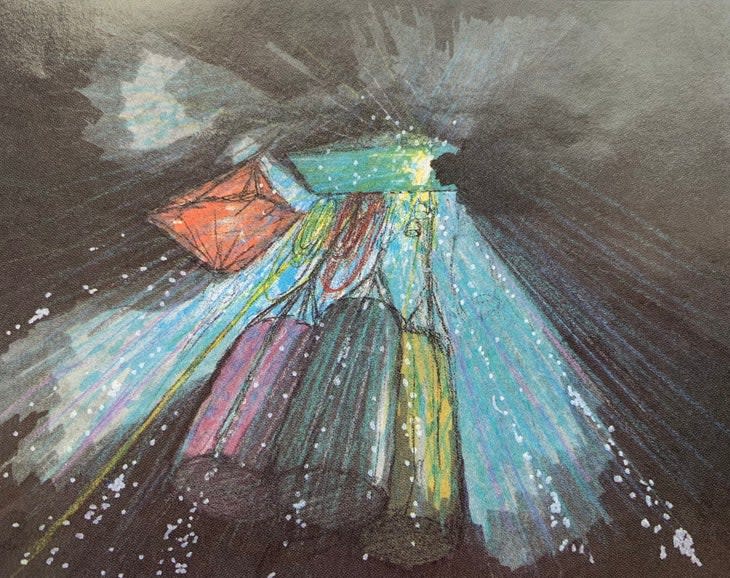

I was in a boxing ring, packed full of every variety of boxer and pro wrestler imaginable, each mistaking me for his training bag before a big fight. One of them was trying to crunch my skull

Inside my ledge, I made constant efforts to keep from being completely buried. Huge water-saturated snow piles would rise in moments; I would use all my strength to push them off one end of the ledge, then notice that at the other end snow was piling up fast. A minute of inactivity and the weight of the snow would begin to crush me, tearing the fly apart at the seams, and become almost too heavy to push off. This went on for hours. Because of the angle of the wall above, and the distance in which the snow could accumulate and slide down, the snow was essentially coming down at the rate of several feet per minute.

Toward dusk, exhausted by my vigilant efforts, I dozed off, though I knew myself to be on the verge of hypothermia. It was pleasant. But then, suddenly, I was in a boxing ring, packed full of every variety of boxer and pro wrestler imaginable, each mistaking me for his training bag before a big fight. One of them was trying to crunch my skull when I snapped awake. Steve was stepping on my head.

Mike and Steve, seeing that my ledge had become completely buried by snow, had yelled for me with no response and thought maybe that I had died. Unable to see even where my ledge hung, Steve had kicked steps in the frozen layer of snow and ice across the near-vertical wall to investigate. In my stupor and because of the dampening effect of the thick snow cover, no sounds had penetrated--only his foot. "Glad to see you're all right, old buddy," he said before returning to his and Mike's hovel.

It was dusk, but sleep, I realized, would be fatal. I tried to keep my mind busy. I thought about new portaledge designs, and shook my head, legs, and hands rapidly for warmth in my cramped quarters, by now reduced to the size of a small doghouse. In sets of 100, I counted to 22,000, twitching with each count.

Eventually I told myself that many hours must have passed since darkness fell. I looked at my watch. It was 10 p.m.

Steve and Mike, with the marginal benefit of ensolite and double boots, sat on a single portaledge, one fly draped over their heads, beating on each other for warmth and to prevent sleep.

It occurred to me that we were experiencing some of the worst storm conditions to be found anywhere. If the route was steeper, things might have been OK. If the winds weren't accelerated by Little Yosemite Valley's venturi effect, things would have been so bad. But mostly, if the temperatures had remained either above or below freezing, we would have been sitting pretty--relatively--either in a wet rainstorm or a blizzard.

Sometime in the early hours of Sunday morning, the storm faded and the stars appeared. The absence of the deafening wind seemed strange and eerie. Steve and Mike were the first to broad the potent silence, and we briefly discussed first-light retreat plans. It soon became apparent that the clearing storm was a mixed blessing; radiation heat loss into the clear sky sucked the last bit of heat from our bodies. The most bitter of bitter cold prevailed. We struggled through each remaining moment of a long night.

In the morning, the sun finally appeared. The comparative warmth stunned us into passiveness for a while. We basked in the above-freezing temperatures and procrastinated for a few blissful moments. But we could see another storm approaching in the distance, so we started hacking out the ropes and made ready for what would be a horrendous descent. We were all functioning slowly and clumsily but thought we could probably make it down alive. Not a bit of rock was visible; the entire wall was covered with a four-inch layer of ice.

Then came the avalanches. As the sun warmed the loosely attached stratum, hundreds of pounds of softball-sized chunks of ice began to crash down on us. Mike and Steve had helmets, while I stuffed soggy socks in my Peruvian hat for protection. Under one barrage, Mikes suddenly plummeted several feet, when the bolt supporting his ledge popped. Luckily, the anchors at each side held. From above Steve and I stared for a few moments at a wide-eyed Mike, still standing upright in his ledge. Wordlessly, except for a few "Hoo-mans," we resumed our descent preparations.

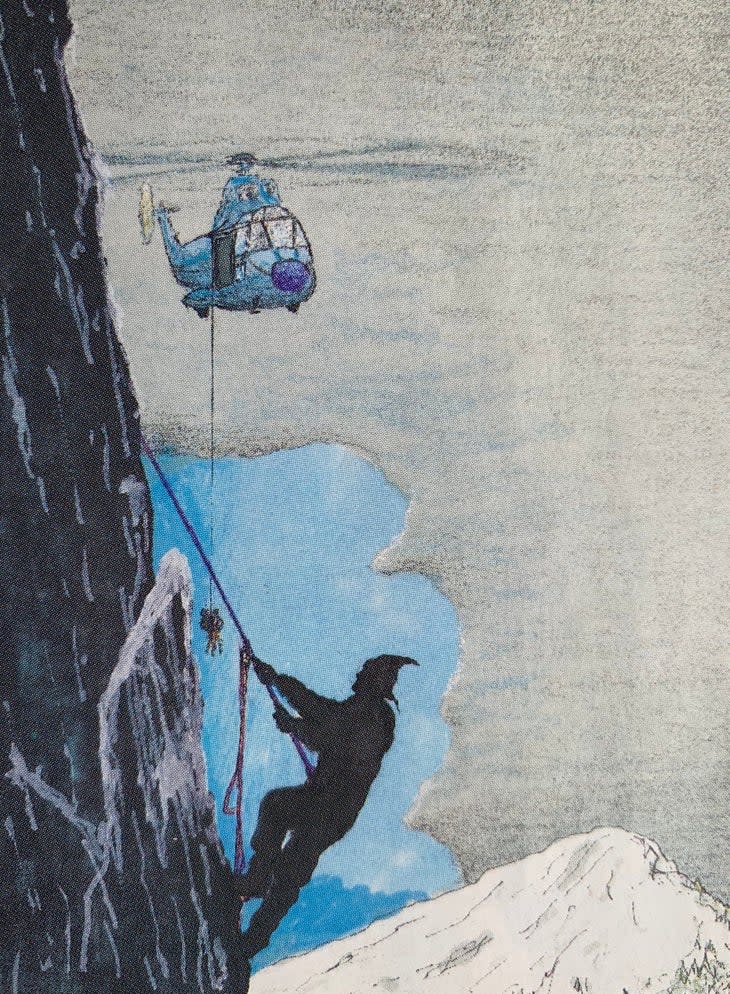

The ropes were still only partially cut out of the ice when we heard it: the whop-whop-whop of a helicopter. An emotional wave swept through us. In silent disbelief, we watched the chopper pass and fly almost out of sight. "I sure hope that's for us," I thought. Then it returned, and amidst continued avalanches, locked into place hovering 100 feet above us. An angel in a pilot's suit lowered out--Petty Officer Davis from the nearby LeMoore Naval Air Station. We were saved.

Mike volunteered for the first ride, and was hooped under his armpits with a "horse collar" and lifted off. Steve and I watched Mike and Officer Davis dangle from the helicopter as it disappeared down the valley. We tossed some haulbags and sleeping bags and endured more avalanches.

Eventually the helicopter returned, picked up Steve, and took off again. Ten years ago, helicopters that could lock into a stationary flight pattern so close to a cliff didn't exist. Despite technological advances, I was amazed at the pilot's ability to counter every gust of wind. The spinning rotor blades sometimes came within a few yards of the cliff. The wind was whipping up again, and it seemed like the pilot had a more difficult time locking in place for Steve's hoist. Fearing the worst, I imagined being stranded on the wall alone, bivy gear tossed.

....he stopped right in front of me. I grabbed his outstretched hand, slipped into the "horse collar," unclipped from the belay, and went for the ride of my life.

After what seemed like ages, the helicopter returned, but it took a couple of tries for the pilot to lock into place. Officer Davis, dangling 100 feet below the machine, darted to and fro just out of my reach, signaling to the pilot for positioning. Then, with a thumb's up signal to the pilot, he stopped right in front of me. I grabbed his outstretched hand, slipped into the "horse collar," unclipped from the belay, and went for the ride of my life.

As we flew toward the valley, dazed by the view, I didn't notice that we were being winched up. Unexpectedly, the helicopter was directly above us, and I clambered into the cabin.

A huge crowd and several other helicopters greeted us in the Ahwahnee Meadow. The extent of the rescue effort astounded me, with over 30 people involved (many of whom had hiked all night in waist-deep snow and were still near the base of the Half Dome cables), and four helicopters ready to go. A sudden feeling of overwhelming gratitude intoxicated me. The LeMoore Station and the Yosemite Rescue Team had coordinated the effort admirably, and it was thanks to them that we were all alive.

I stepped out of the helicopter and my legs buckled; I hadn't walked for a week. I staggered toward my friends, Jim and Tory, who whisked me away (barely escaping the pouncing paramedics) and took care of me in Jim's warm house, where I shivered uncontrollably for several hours. Meanwhile, over at the Yosemite Clinic, Mike was being poked and prodded, given IVs and warm oxygen, and a splint for his finger.

At Jim's, I mindlessly leafed through the Sunday newspaper. I became entranced by a particular photo in it, nothing registering at first. Then I realized I was looking at a picture of Warren Harding in 1970 standing on The Ledge. He seemed to be smiling at me. Coincidentally, the newspaper had done a feature article about the South Face the same day we were fighting for our lives on it.

Later that evening, an unidentified feeling gnawed inside me. The transition from one reality to another made both seem unreal. I realized that all my instincts insisted that I return to a soaked sleeping bag, shiver, stay awake, and generally fight for my life. It seemed we had been up on Half Dome for a lifetime, and I had developed a routine for staying alive that I could not shake.

Instead, I hobbled back to my dry VW van, pulled out a dry sleeping bag, cranked up the propane heater, and passed out--not to stand in etriers on a big wall again until the fall of 1989.

During his epic-induced, big-wall hiatus, John Middendorf focused on getting his climbing supply business, A5 Adventures, off the ground (it was acquired by The North Face in 1996). One thing he has worked hard to improve was… portaledge technology. After regaining his psych, Middendorf and Valley local Walt Shipley completed a difficult new route on the Northwest face of Half Dome, Kali Yuga (VI 5.10 AV).

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.