New York City's Nightlife Past Is the Key to Its Future

No, things were not better then, I remind myself whenever I succumb to bouts of nostalgia about the glory days of New York. The defining moment, in a supercharged city whose essence is change, is always and axiomatically now. “I despise when people say things used to be so great,” says Kim Hastreiter, who as a founder of Paper magazine has had a front row seat at New York’s cultural arena for more than three decades. “It is always better now. Now is when it’s best.”

The topic is club life. If it has seemed to some in recent years that Manhattan clubbing has died (an all but inescapable conclusion even before the pandemic), they just weren’t looking in the right places. Yes, gone are the warehouses, the storefronts, the dive bars, the deconsecrated churches, the Harlem lofts, the Garment District buildings in which so much of what came to occupy a central place in pop culture—disco, hip-hop, house music, vogueing, DJ culture, break dance, drag—was incubated. Yes, they have been replaced by hermetic glass malls surrounded by zillion-dollar condos.

But the raucous and messy nightlife fostered in Manhattan’s seedy margins between the 1970s and the mid-1990s simply migrated over the past decade to the boroughs: to stealth parties and roving techno cult raves in old hotels, an office building in East Williamsburg, a cavernous bar in Queens, a loft where DJs played 12-hour sets in desolate industrial Brooklyn until and beyond the sunrise.

In the renegade spirit of those parties, you can trace a lineage to all the other parties that made New York the global capital of nightlife for decades, from Depression-era speakeasies to the Stork Club and the ’80s mosh pit parties staged by promoters like Susanne Bartsch. Sure, there were cacophonous and largely irreplaceable scenes elsewhere—in Berlin, London, Paris. None, however, fostered cultural production at the level of New York’s. None has been as democratic, or as hybridized and blended.

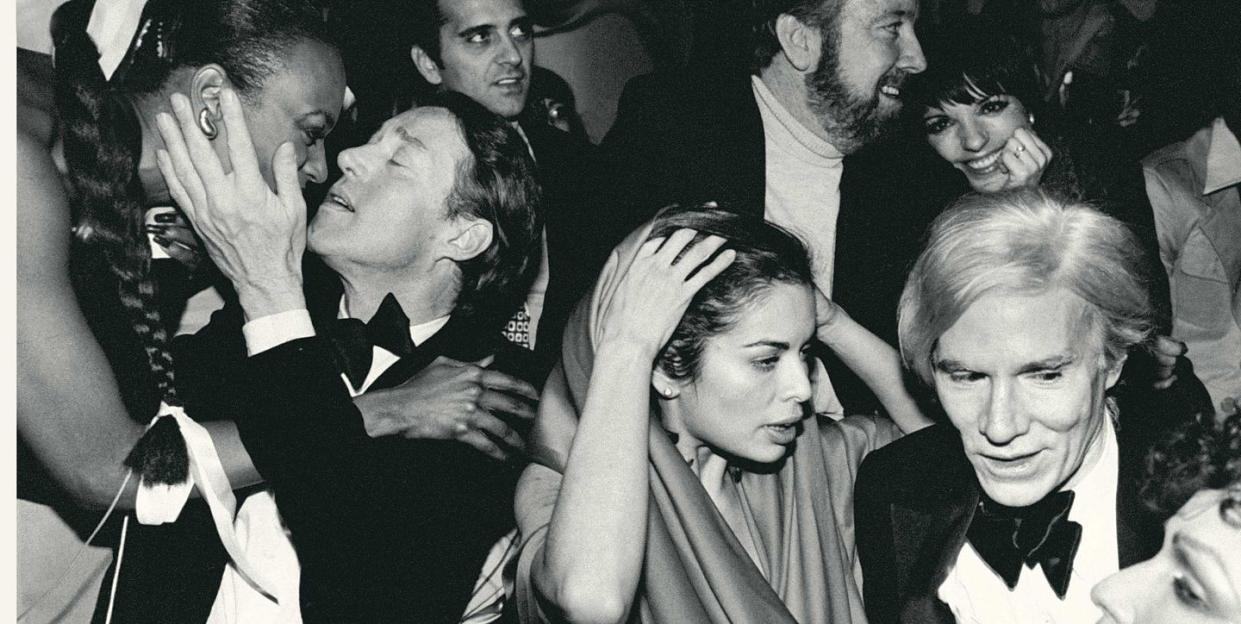

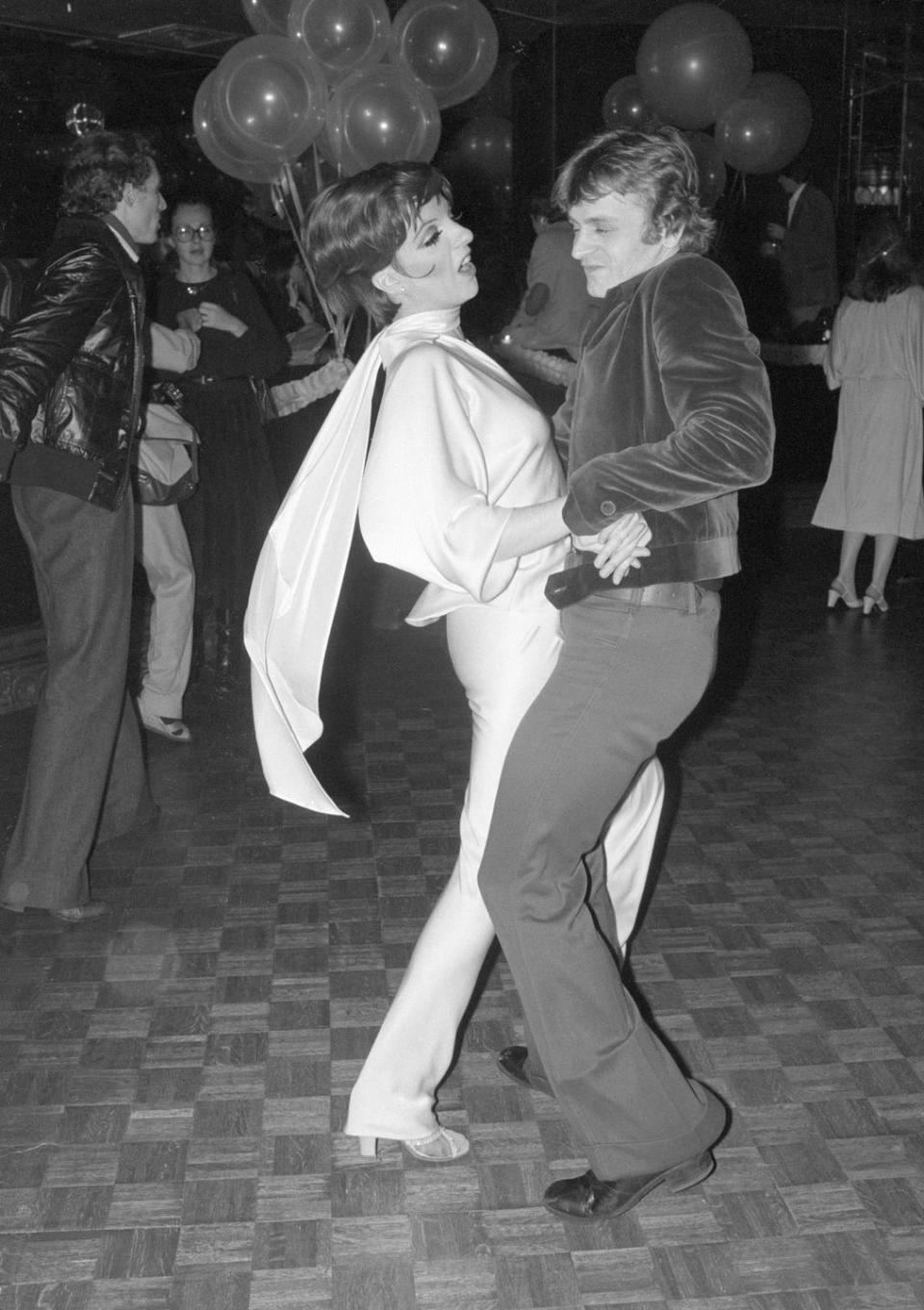

“Steve Rubell [the founder of Studio 54] called it the mixed salad of cultures,” says Eric Goode, a founder of Area, the famed ’80s club in Tribeca renowned for its changing tableaux vivants, staged diorama fashion, starry clientele, and cocaine-dusted antics transpiring in its coed bathrooms. “That was something New York brought to nightlife: that mix of every gender, gay, straight, young, old, Black, white, Latin, whatever,” says Goode, these days the filmmaker responsible for the Tiger King juggernaut.

For those of us who were alive in that era, just saying the names of places like the Tenth Floor, Paradise Garage, Boy Bar, Better Days, Area, the Pyramid Club, the Building, Palladium, Milky Way, Limelight, Twilo, Tilt, Tunnel, and Mars is to invoke an array of almost biblical begats.

Out of those clubs came talents as varied and influential as Madonna, Moby, Deee-Lite, RuPaul, Stretch Arm Strong, and DJ Frankie Knuckles, to cite only a few of the most broadly influential. Long before he began racking up awards for his collaborations with Amy Winehouse, Miley Cyrus, and Bruno Mars, Mark Ronson was a fledgling DJ at NYU. He got his first break playing such popup Manhattan nightclubs as Giant Step and Soul Kitchen for what he later termed “the most beautiful array of models, rap stars, ballers, art kids, skaters, and drug dealers” on the planet.

“You could reinvent yourself as whatever you wanted to be,” says Joey Arias, a performance artist perhaps best known for his Billie Holiday impersonation and an eight-year stint as the dominatrix emcee of Zumanity, Cirque de Soleil’s show in Las Vegas. “That was the secret of it. That diversity is the living symbiotic battery that feeds New York.”

When that diversity eventually dwindled, as foreign investors and the banking class overtook the impecunious artistic one, Manhattan club life began to lose some of its vigor. “Money, real money, was introduced at the end of the ’80s, and that changed everything,” says Serge Becker, co-founder of Area and the Bowery Bar. “You saw it in the art world, where suddenly art is an asset class and some guy is saying, ‘I know how to collateralize it.’” He adds, without evident regret, that when the sets Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring created for one Area theme night had served their purpose, work that would have later been worth millions was unceremoniously scrapped.

For the twilight of a certain lustrous kind of nightlife you can also blame the internet. Privileged word of mouth seems as outdated a concept as the club door guardians who once waved undesirables away. No one—in the era of Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, and TikTok—needs a tipoff. But social media isn’t a death knell, either. Just ask the Gen Z rebels who, pre-pandemic, were staging weekly guerrilla parties at secret locations announced in flash posts on Instagram. “One kid I know,” Hastreiter says, “goes to some empty, fucked-up lot in the middle of nowhere with a van and a sound system and dances all night with his friends. That’s way more interesting to me than stories about ancient club life. It’s always true in New York: What matters most is whatever the kids are doing right now.”

And that is, now as much as ever, going about the important business of reinventing culture.

This story appears in the December/January 2021 issue of Town & Country.

You Might Also Like