Yes, Protests Do Work—Even When It Seems Like the Battle’s Already Been Lost

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

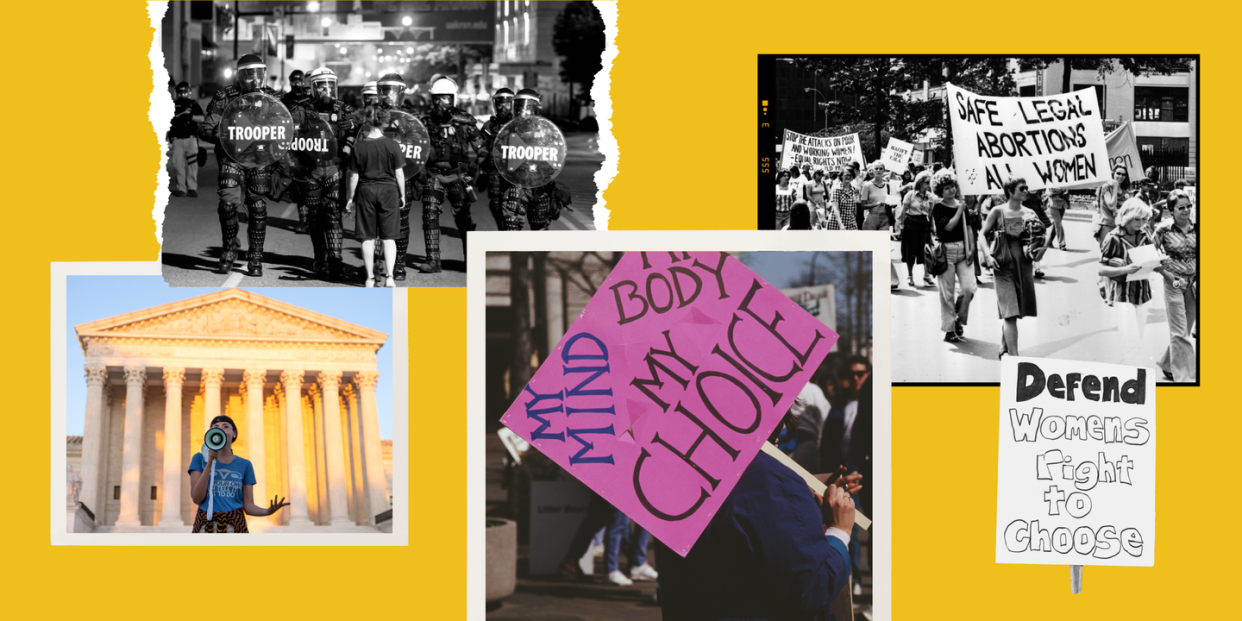

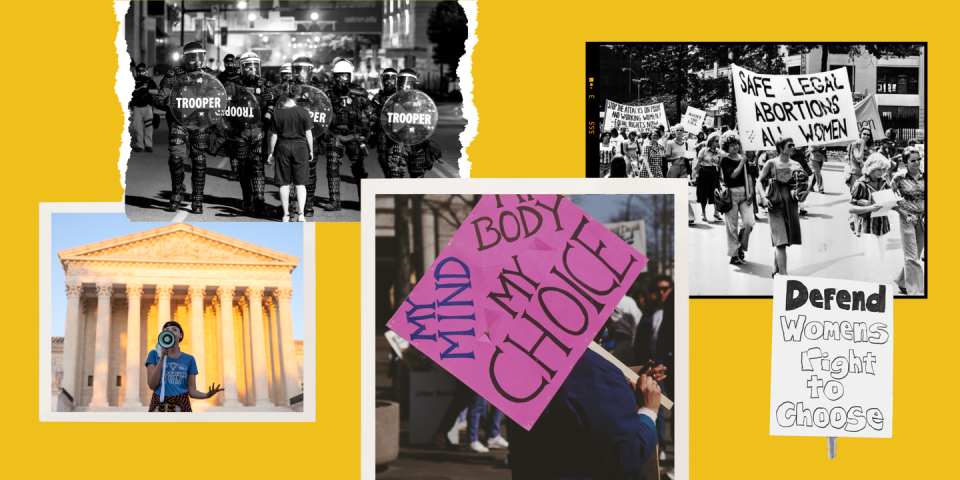

Following the Supreme Court decision on June 24 to overturn Roe v. Wade, the nation exploded in outrage. Faced with what The Washington Post called a “reckless fit of judicial activism,” people all over the country took to the streets in large numbers to protest the court’s decision. In Birmingham, Washington D.C., New Orleans, Philadelphia, Seattle, San Antonio, Oakland, and more, thousands turned out with myriad demands, outcries, and affirmations on their signs.

At the protest I attended over that weekend in New York City, I heard chants and saw signs that spoke to a range of backgrounds and emotions: “Abortion is a human right not just for the rich and white”; “Reproductive justice is racial justice”; “Thank God for abortion”; “Trans dykes for abortion rights; “Anti-abortion laws kill us”; “We will not go back.” I attended the protest after first calling my mother and crying in despair when I heard about the ruling Friday morning. The protests were cleansing and activating, in a way that only protests can be: a life-giving reminder that when our institutions fail us, we have and always will take care of each other, that we are not alone in this fight.

Strength in Numbers

In the past few years, we’ve seen some of the largest protests in American history—with some studies showing the 2020 George Floyd protests as perhaps the largest in American history. Whenever these public showings of activism pop up, media and spectators alike share grumbling tweets and think pieces about whether protesting works. But if protests don’t work, or are a waste of time, then why are our institutions and police so hell-bent on stopping them? And if they do work, how do they work?

I posed these and other questions about Roe and the benefit of social movements to LaGina Gause, PhD, assistant professor of political science at UC San Diego and the author of The Advantage of Disadvantage: Costly Protest and Political Representation for Marginalized Groups.

Gause cites the recent gun rights legislation that swiftly passed through the Senate—a bipartisan bill that expands background checks and closes the “boyfriend” loophole”—as proof that protests can move legislators into action: “Gun rights has been a conversation for decades, without any progress. Why now? Because people are fed up and they aren’t taking no for an answer.”

The interesting thing about so many people taking to the streets for abortion rights is that it came amid concurrent—and sizable—protests on other issues as well. “It’s not just abortion that’s being protested about. There’s gun rights, there’s immigration, and there are the ‘Fight for $15’ protests to demand a higher minimum wage. There are labor strikes and the great resignation.” From a political science perspective, this state of affairs does not necessarily bode well for long-term legislation: “Legislators may recognize that people want things done. But they also think that voters won’t stay as engaged as they are right now.” Cue the argument that the bipartisan bill on gun legislation did not go far enough: e.g., the “boyfriend loophole,” an aspect of the bill that bars convicted domestic abusers from buying a gun unless they are first-time offenders, in which case the legislation would waive this restriction after five years if they are not convicted again. According to Gause, the thinking of some lawmakers is: “We need to survive this moment. Maybe this legislation will get people to calm down and stop being so active on gun legislation.” Fortunately, protestors know this, and many activists have devised strategies to cope with burnout.

Finding Your Political Family

But legislation is not the only reason to protest. Many of the current protestors are feeling abandoned by what they see as the inaction of the Democratic Party, which failed to protect and codify Roe despite warning signs that the court was likely to overturn the ruling. In a two-party system such as ours, the voices and perspectives of marginalized groups aren’t always adequately represented by only two voting choices. Protests are a way for people to take action instantaneously and with agency, to come together and make their voices heard. Some protests may not seem to have an immediate impact but have a long legacy.

A recent example is Occupy Wall Street, a protest movement against widespread income inequality in 2011 that I participated in. A frequent critique of OWS at the time was that the movement was leaderless and without concrete demands. In her book Direct Action: Protest and the Reinvention of American Radicalism, L.A. Kauffman argues that OWS’s “signature political move” of what organizers called “dreaming in public,” or holding participatory public debates about what a more egalitarian world would look like, spurred action and concrete change for years to come: “Occupy created a new sense of political possibility. Veterans of the encampments fanned out across the country to launch or support diverse activist initiatives.” One direct effect of OWS-helmed initiatives is the Debt Collective, the nation’s first debtors’ union, and Strike Debt, the broader movement to cancel student debt, which has pushed the idea of student-debt cancellation from the fringe into the mainstream. Case in point: President Joe Biden, who ran on a promise of canceling student debt, is expected to cancel at least $10,000 of debt by federal borrowers in August. Activists hope this is just the beginning.

Gause agrees that in order for protests to have long-term impact, they need to go beyond lawmaking and voting: “A social movement isn’t just about legislation. It’s about building community and ground-level capacity building—trying to influence not just legislators but also the media, as well as hearts and minds.” The George Floyd protests, and the Black Lives Matter movement more broadly, are a salient example of protests having the power to change public opinion. In fact, “racial attitudes started to shift after the first BLM protests in 2014,” according to The Washington Post, with more Americans than ever before holding the belief that the country has a problem with anti-Black discrimination. The Floyd protests have only accelerated that trend. And according to a study by FiveThirtyEight, in the immediate aftermath of the Floyd protests, phrases like “defund the police” and “police abolition” saw a marked uptick in Google searches. These increased searches suggest that the mainstream is gaining comfort with ideas that have long been central to the BLM movement but elsewhere were considered radical or fridge ideology.

When it comes to abortion, many pro-choice advocates cite the fact that a majority of Americans support the right to choose—so why focus on convincing more citizens? The reason is the distribution of that opinion. Gause explains that “if 60 or 65 percent of Americans [are said to support abortion rights], that’s of the entire nation, right? But we really need these numbers at a state level, otherwise, it doesn’t tell us much. This is why protests matter; they tell us how intensely people care about an issue. If you [are a state representative and you] look outside your window and there are a bunch of people at your state capitol protesting,” that can be more galvanizing than poll numbers.

On some occasions, the deciding vote may be your friend or neighbor rather than your representative. On August 3, in a popular referendum, Kansas voted to protect reproductive rights rather than allow state legislators the power to revise the state constitution. That referendum, which requires ordinary citizens to turn up to polling places and cast a vote like they do for a general election, had some of the highest voter turnout the state has ever seen. How much of that enthusiasm was due to protest is hard to gauge, but it proves that individual votes and popular discourse do matter.

Going All In

In her book, Gause also discusses the notion of “costly protest,” or protests where people are “willing to pay dire costs over an issue,” as being very effective. On the Saturday following the Supreme Court decision, there were already reports of nationwide police violence at abortion rights protests. In Arizona, police wielded batons, fired tear gas, and forcibly removed protestors from public spaces. In New York City, more than two dozen protestors were arrested in Washington Square Park, Union Square, and in front of the Fox News building in Midtown. In South Carolina, six protestors were injured by police. In Cedar Rapids, Iowa, a man drove his Ford pickup truck into a group of female protestors, putting one of them in the hospital. In Los Angeles, the city I’m from, police were seen assaulting women, including Full House actor Jodi Sweetin and at least four journalists with press badges, including my brother-in-law, Lexis-Olivier Ray, who has been repeatedly targeted by police for his reporting on protests for L.A. Taco. Says Gause: “[Protestors] wouldn’t do it if they didn’t really care. [It says:] I really care about abortion and I’m going to show up even if I know that police might get hostile.”

Witnessing the fervent dedication of protestors is particularly meaningful in the fight for abortion rights. In the face of widespread abortion bans in their state, many people are very afraid. But “when they go out into a protest, they see that they aren’t alone in this struggle. That’s really important, especially in the immediate aftermath [of Roe being overturned] to make sure people know that other people are similarly concerned about this issue; that there is community.”

Unfortunately, there is some danger associated with protests. Americans stay silent at their peril. Even before Roe was struck down, abortion was already unsafe or unavailable for many people in the United States. This was especially true for those living in one of the 27 cities where one has to travel 100 miles to get an abortion, or are one of the 18 to 37 percent of women on Medicaid who would otherwise get an abortion but are forced to give birth because of lack of funding. And let’s not forget Texas, where a host of anti-abortion laws in the past year had already made abortion care all but illegal in the state. “There’s always been large segments of the population that haven’t had access to sufficient healthcare,” says Gause. Even in the states that permit abortion, some of the laws around [requisite] counseling can put a person so far into the pregnancy that it becomes less safe to get one. I guess if we want to try to find a silver lining to the Roe [decision], it is calling attention to some areas of healthcare that were already pretty bad and could use a change.”

As I sat down to write this piece, I recalled another sign I had seen over the weekend: “You are right to fear our rage.” On a gut level, I already knew that this was true, that protests work. Having spoken to Gause and conducted my own research, I can prove it, too.

You Might Also Like