Yellowface, Whitewashing, and the History of White People Playing Asian Characters

Paramount Studio’s 2017 live-action adaptation of the classic Japanese anime Ghost in the Shell opens to the soundtrack of a haunting chant in Japanese while surreal images of cybernetic body parts coalesce into a naked female form. As the artificial body emerges from its womb-like incubator, the outer encasement peels away to reveal the face of a black-wigged Scarlett Johansson as the film’s protagonist, Major — eventually revealed to be the cyberized reincarnation of a young Japanese girl named Motoko Kusanagi.

For defenders of Ghost in the Shell, deft screenwriting enabled Johansson — who is not Japanese — to play the lead role of a Japanese woman. But, for many Asian-Americans, Johansson’s casting was just the latest in a long pattern of Hollywood selecting white actors in Asian roles to make Asian characters more palatable for white audiences. Some Asian-American protesters felt the film was an example of yellowface — a term referencing when a white actor dons “Asian-esque” stage makeup and costuming to play an Asian character. Others lambasted the film for how the script adapted its Japanese source material to allow for a white actor to play the role of Ghost in the Shell’s iconic Japanese protagonist — a process termed “whitewashing” by its critics.

Keith Chow — founder of pop culture blog The Nerds of Color, which co-organized protests on social media against Johansson’s casting in Ghost in the Shell — believes that both yellowface and whitewashing were evident in that film. He sees whitewashing as a contemporary revival of historic yellowface: a practice related to American traditions of blackface and, like blackface, popularized in early American theater and cinema.

“It’s all connected,” Chow tells Teen Vogue. “It all results in the dehumanization of people of color; and, in the specific case of yellowface, in the dehumanization of Asian people.”

GHOST IN THE SHELL, Scarlett Johansson, 2017. ©Paramount Pictures/courtesy Everett Collection

One of the earliest documented examples of yellowface is the mid-18th-century production of The Orphan of China, adapted from the 13th-century Chinese play The Orphan of Zhao. Critics of the production later remarked that the show’s popularity was due to the production’s “Oriental” setting and its liberal use of Chinoiserie (the imitation of Chinese motifs and techniques in Western art) and white actors in yellowface. This yellowface predates the earliest landing of Chinese immigrants on American soil by nearly a century. The Orphan of China was thus not a realistic portrayal of China; rather, it was an elaborate fiction drawn from the audience’s collective imagination of Chinese people. Yellowface would soon become an enduring tradition of American theater that would persist as a popular practice for centuries.

The earliest practitioners of yellowface sought to transform white actors into Asian characters using skin-darkening pigments and makeshift contraptions of tape and rubber bands. The look would be combined with an over-the-top performance that included exaggerated accents and other physical tics. Yellowface was considered a bona fide technique mastered by skilled makeup artists, and instructions were published in technical manuals as recently as 1995’s The Complete Make-up Artist by Penny Delamar.

The harm of yellowface was described by Robert G. Lee in his book, Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture: “Yellowface marks the Asian body as unmistakably Oriental; it sharply defines the Oriental in a racial opposition to whiteness,” he writes. “Yellowface exaggerates ‘racial’ features that have been designated ‘Oriental,’ such as ‘slanted’ eyes, overbite, and mustard-yellow skin color.”

For the better part of American history, actors would don yellowface to assume Asian identities in theatrical productions while laws (including the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and the Alien Land Laws) effectively barred Asians from integrating into most aspects of American society. Media industry customs and guidelines (such as the Hays Code) restricted the casting of non-whites in any role where they might be perceived as a love interest of a white actor’s character; ultimately, this custom often was cited as justification for casting white actors in yellowface. Rather than allow Asian actors to accurately represent themselves, audiences apparently preferred the fictionalized Asian “other” as it was projected through the caricatured yellowface antics of a white actor.

Yellowface proved a wildly successful career move for many white actors and entertainers. Mid-19th-century magicians invented Chinese personas to imbue their acts with an aura of Far Eastern mysticism. For example, despite his Scottish heritage, New York–born William Ellsworth Robinson wore a long black wig and Chinoiserie costume and spoke in nonsense Chinese to lead a lengthy career as the famed stage mystic, Chung Ling Soo.

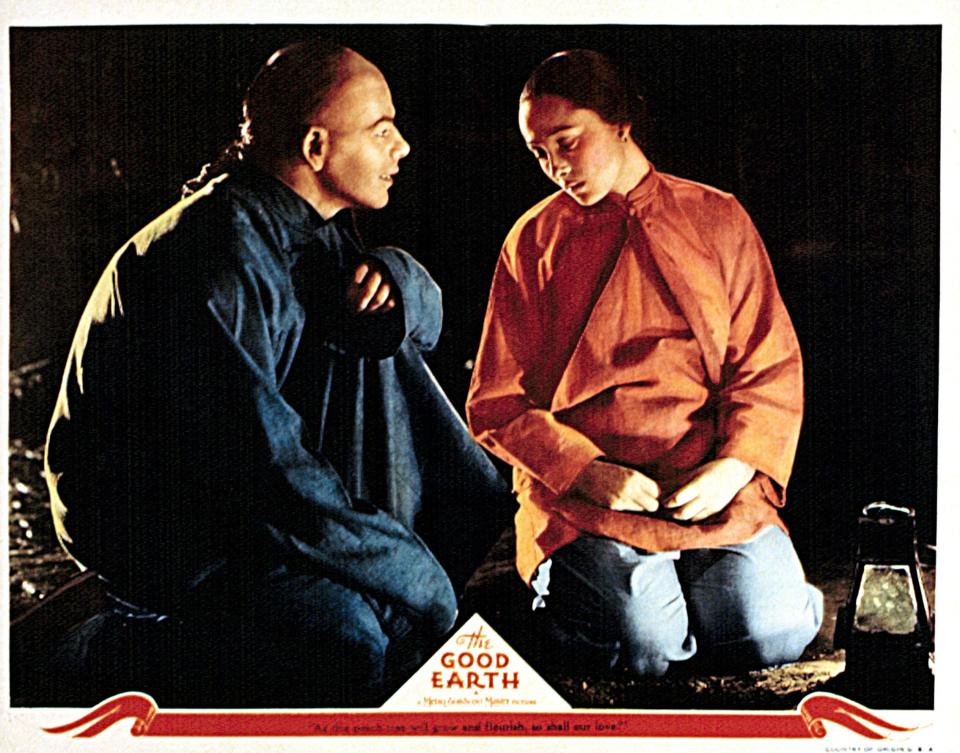

THE GOOD EARTH, Paul Muni, Luise Rainer, 1937

With the proliferation of moving film into popular culture during the early 20th century, yellowface made the transition from stage to silver screen. Swedish-American actor Warner Oland led a storied career that spanned decades as a highly sought-after yellowface actor. He routinely played Asian characters, including the first live-action depiction of the villainous Dr. Fu Manchu, and the bumbling Chinese-American detective Charlie Chan in 16 full-length films. Other famed actors such as Katharine Hepburn, Fred Astaire, Yul Brynner, Peter Sellers, Marlon Brando, Mickey Rooney, and John Wayne all took a turn at yellowface. In a testament to the mainstream acceptance of yellowface performances, German-American actor Luise Rainer won an Academy Award for her depiction of Chinese peasant O-Lan in 1937’s The Good Earth — a role in which Rainier wore a black wig and “facial inlays” to camouflage her Caucasian features, and in which she allegedly was originally set to wear a rubber mask to better achieve the “Chinese look.”

Producers of The Good Earth allegedly decided to pursue white actors in yellowface for the film’s leads because they apparently deemed American audiences to be unprepared for a feature film starring an ensemble cast led by Asian actors. That racial calculus remains popular dogma for major production studios some 80 years after The Good Earth first opened in theaters: in a YouTube video explaining the casting of Scarlett Johansson in Ghost in the Shell, Hollywood screenwriter Max Landis responded to critics who were “not understanding [of] how the industry works.”

Although Asian-Americans are the fastest-growing population of Americans, they remain seriously underrepresented in popular American entertainment. In a recent University of Southern California study, researchers found that only 4.4% of speaking characters are Asian in popular American film. Meanwhile, about 1% of Academy Award nominations for acting have gone to Asian or Asian-American actors, HuffPost reports. That same pattern holds true for American television: according to scholar Nancy Wang Yuen, author of Reel Inequality: Hollywood Actors and Racism, nearly two-thirds of broadcast television shows — including those set in cities with sizable Asian-American populations, like New York City — lack any regular Asian-American characters whatsoever, she tells Teen Vogue.

While the use of yellowface still occurs in contemporary film, use of stage makeup to achieve yellowface is rare and has generally fallen out of favor. Yet, white actors continue to be cast in roles originally conceived to be Asian or Asian-American; now, however, that feat is accomplished through script rewrites and casting choices rather than stage makeup. Recent examples include Aloha, Dr. Strange, Annihilation, 21, and live-action adaptations of popular Japanese animated titles including Ghost in the Shell, Death Note, and Dragonball: Evolution.

“It’s part of the same lineage,” Yuen says. “Whitewashing is a descendant of the original yellowface. It’s all part of the same story in American media: the underrepresentation, misrepresentation, and usurping of significance of Asians by white actors.”

“Why is the erasure of Asians still an acceptable practice in Hollywood?” asks Chow in a 2016 opinion piece for The New York Times. This question captures the central concern expressed by Asian-Americans who have organized numerous protests against whitewashing and yellowface.

One of the earliest such protests was in 1990, when the musical Miss Saigon was set to open on Broadway. Members of its original London cast were slated to reprise their roles for the American production — including white actor Jonathan Pryce, who had worn heavy-lidded eye prosthetics and bronzer to play the biracial French-Vietnamese character, The Engineer, for the show’s London performances. Meanwhile, Asian actors were reportedly not “seriously considered” for the part on Broadway.

Outraged Asian-American activists organized a national campaign to criticize yellowface in Miss Saigon, as well as the show’s portrayal of villainous Asian men and passive, self-sacrificing Asian women as ancillary to the heroic narrative of white men. That grassroots protest led to the Actors’ Equity Association declaring that it could not “appear to condone the casting of a Caucasian actor in the role of a Eurasian” and held a vote to prevent Pryce from taking the role. In response, producers briefly canceled the production until the AEA reversed its decision. Miss Saigon went on to enjoy a 10-year run on Broadway and a brief revival in London in 2014, and Pryce received a Tony Award for his performance. (In a recent interview, Pryce seemingly expressed no regret for taking the role.)

“It is the height of white privilege to think a white person is better equipped to play an Asian character than an Asian person,” actor Sun Mee Chomet tells Teen Vogue, who is primarily angered by the stereotypical and misogynistic portrayals of Asian women in Miss Saigon. “Miss Saigon reinforces and reaffirms all of the racial, gendered Orientalist stereotypes that box Asian-Americans in,” agrees poet Bao Phi. Chomet and Phi joined several Asian-Americans to campaign against a planned production of Miss Saigon at Minneapolis’s Ordway Theater in 2013. Across the country, similar protests have also occurred against productions of The Mikado, which routinely casts white actors in its Japanese roles.

THE LAST AIRBENDER, Noah Ringer, 2010. Ph: Industrial Light & Magic/©Paramount/Courtesy Everett Coll

Marissa Lee, who co-founded the group Racebending and led a national campaign against whitewashing in the 2010 film The Last Airbender, cites the 1990 Miss Saigon protests as her inspiration. “We built off of the Miss Saigon campaign and looked at how they did it,” Lee recalls. Lee wanted to use the controversy around The Last Airbender to revive the conversation around the racial implications of Hollywood casting decisions. “It’s impossible to look at whitewashing without considering it in the context of employment discrimination,” Lee says. She notes that there has been an exodus of Asian actors going to Asia because they cannot find work in Hollywood, which only compounds the invisibility of Asians in American media.

Racebending was one of the earliest campaigns to bring the conversation around racial diversity in Hollywood to the digital sphere. Since then, Asian-Americans have continued to use social media to target whitewashing and Asian underrepresentation in Hollywood — including through trending hashtags such as #StarringJohnCho and #SeeAsAmStar (both created by Twitter user William Yu), #WhiteWashedOut (co-created by Chow), and in viral parody videos, such as those created by Tow-Arboleda Films. Thanks to efforts like these, “it’s looking more like a bad career move for white actors to participate in whitewashing,” says Lee, citing actor Ed Skrein’s recent decision to back out of playing a Japanese-American character in the Hellboy reboot.

“So long as whitewashing continues to occur, we need to be conscious of whose stories are being marginalized and whose stories are not being told in mainstream media,” cautions Yuen. Indeed, campaigns against Hollywood whitewashing and yellowface have brought fresh awareness to issues of diversity in American media; more tangibly, they have also inspired a proliferation of self-published Asian-American media.

“We’re in the middle of a renaissance in Asian-American film and theater,” Chomet says. She argues that Asian-American actors need not settle for taking background roles in whitewashed productions that perpetuate stereotypes about Asians. “We need to consider the impact of when media uses damaging stereotypes and centers the white gaze, and we have a responsibility to not participate in them.

“Asian-Americans are creating so many of our own opportunities by writing our own stories right now. Our energy is best used in the creation of our own stories and demanding a permanent seat at the creative table,” she says. “We have the power to render racist representations of ourselves as obsolete."

Let us slide into your DMs. Sign up for the Teen Vogue daily email.

Want more from Teen Vogue? Check this out: