How Writers On LSD Changed Marvel Comics Forever

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

In 1986, the comic book—after a lengthy adolescence—finally grew up.

Consider the year’s stacked line-up: Frank Miller’s seminal four-issue Batman: The Dark Knight Returns; Alan Moore’s and Dave Gibbons’s Watchmen; the first collected volume of Art Spiegelman’s Maus; American Splendor: The Life and Times of Harvey Pekar; and Daniel Clowes’s first comic, Lloyd Llewellen, all launched that year. These are some of the most important artists and titles in the history of the form. Like 1975 in film and 1922 in books, 1986 in comics fissured the timeline into Before and After. These seminal works were praised for doing things, going places, and addressing topics that conventional comics wouldn’t, which is another way of saying they were more adult, serious, and thematically complex. The cover story of the August 1986 issue of The Atlantic was titled, “Comic Books for Grown-Ups.”

In Jeremy Dauber’s fascinating book American Comics: A History, he notes two crucial—and seemingly related—points about the comics industry in the late ‘70s: at the time, “Scholars pegged the reading level of twenty popular comic book titles as ranging from 1.8 to 6.4. Comics, in other words, were for kids, and increasingly few of them. By 1979, monthly comic book circulation was its lowest since the early ‘40s.” This state of things—comics being immature, unpopular, and creatively stagnant—makes the maturation of the form represented by Miller, Spiegelman, Moore, and others look almost heroic. The adults are here, so let’s get serious.

But what if that narrative was as simplistic and reductive as the pre-’80s comics were accused of being? What if that supposedly stagnated adolescence contained all manner of innovation, experimentation, and maturation that have simply been overlooked? What if the actual groundwork for 1986’s radical departures in the form was laid not just by auteur geniuses, but also by the journeyman practitioners of mainstream titles, whose forced capitalistic productivity led to many formal innovations that often go unacknowledged, languishing as they are in the childish, artless pages of unserious comics?

Eliot Borenstein’s new book Marvel Comics in the 1970s: The World Inside Your Head convincingly argues that writers and artists like Steve Gerber and Don McGregor, who worked on characters like Howard the Duck and Black Panther, made smaller, more incremental contributions to comics, ones that are harder to notice but are ultimately just as vital. This decade in Marvel’s history is often remembered as an awkward transitional period—which it was—but the growing pains felt during this time are just like the ones we experience in our youths: aching pangs that promise future advancement.

“Marvel in the 1970s,” Borenstein explains, “saw a transformation that initially looked seamless on the surface, but proved almost as dramatic as Bruce Banner turning into the Hulk.” The means by which this transformation occurred “were as much about the expansion of possibilities within an industry as they were about the potential of the form itself.” What these creators were up to was societal as much as it was artistic, as their work was “extending the boundaries of the permissible within the comics mainstream.” The ‘60s proved to be a tumultuous decade of social upheaval and shifting demographics, but taboos were still strong enough that most major changes are only referred to underhandedly in pop culture. Songs like “Puff the Magic Dragon” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” couldn’t directly address their real subjects—weed and LSD, respectively—but had to sing around them. Comic books, as we’ll see, employed similar tactics.

$21.42

amazon.com

The biggest shifts, though, occurred in the way Marvel approached the inner lives of these larger-than-life characters and their outer alienation from others. Marvel’s heroes were no longer flat, info-dumping archetypes—or, they were still those things, but with an additional layer of idiosyncrasy. For instance, Shang-Chi, initially a crass, clumsy, and racist Bruce Lee rip-off, is given the rare honor of narrating his story himself, in lieu of Stan Lee’s practice of an omniscient narrator. When writer Doug Moench took over the character (and continued on for a decade), he utilized the first-person perspective to grant readers access to Shang-Chi’s thoughts on the action as it happens, making him, to us, a voice-driven character; but as Borenstein points out, “were it not for his inner monologue, Shang-Chi would run the risk of adding yet another racist stereotype to a book that was loaded with them. He would have been inscrutable.” A character who interacts with others with scant intimacy is, paradoxically, one of the most verbally communicative protagonists to readers. Such an intriguing and fruitful duality is, unfortunately, explored in a comic with a deeply problematic history, and thus it’s been understandably overlooked.

On the alienation side of things, we have Steve Gerber’s Howard the Duck (which he co-created with Val Mayerik), who, because of the stain of George Lucas’s disastrous adaptation from (guess when?) 1986, has become an underrated figure in comics history. Howard the Duck, Borenstein reminds us, was briefly “a mass-culture phenomenon” whose tagline—“Trapped in a world he never made!”—captured the burgeoning resentments of the post-Nixon era (Howard even ran for president in 1976, with the slogan, “Get Down, America”). Not only does Howard’s curmudgeonly attitude toward the absurdity of the Marvel Universe pave the way for Harvey Pekar’s similarly crotchety view of our own universe, but Steve Gerber’s sometimes radical meta-experiments—like an all-text issue, which featured descriptions of drawings instead of actual artwork, including a section called “Obligatory Comic Book Fight Scene”—set the scene for the serious self-consciousness of Watchmen.

With these new approaches to character and culture, Marvel artists set the stage for the radicality of later creators like Moore and Miller. Borenstein, by highlighting these often unheralded contributions, does a real service not just to comics history, but to cultural history in general, as he shows that many of the vital steps in an art form’s growth are built incrementally by lesser-known contributors.

In order to show the full breadth of these achievements, let’s take a brief foray into the world of Marvel just before the era covered in Borenstein’s book to see how dramatically things changed.

Marvel Comics from the 1960s can be a tough hang. Take, for instance, this run of Thor from 1966 by Tom DeFalco and Ron Frenz (who also co-illustrated it with Gary Hartle) called “The Black Galaxy Saga.” When I first dove into the overwhelming largesse of Marvel Comics, I was necessarily indiscriminate in my choice of title. I assumed that the older a comic was, the more old-fashioned and anachronistic it would be—but I had no idea just how clunky comics used to be.

Comprising issues #417-425, the Black Galaxy arc comes from a brief period in which Thor had merged with an architect named Eric Masterson, who could then transform into Thor by using a magic cane. (Don’t even bother asking me how they merged, because it’s classic comic-book convolution, meaning elaborate, arbitrary, and pretty fucking dumb.) This Masterson fellow lives in New York City with Hercules (again: don’t ask), who—for real—lives under the alias Harry Cleese. I get the shivers from how stupid that is.

$7.99

amazon.com

Anyway, none of that stuff, believe it or not, is the reason it’s a tough hang. Those kinds of eye-roll-inducing puns and silly plot mechanics are part and parcel of the superhero experience, to a certain degree. Masterson isn’t even Thor’s first alter-ego: originally, Thor’s father Odin sent him to Earth as a young doctor named Donald Blake (although it’s later revealed that Blake was never a real person, but rather Thor with his memory wiped). What makes comics like “The Black Galaxy Saga” such an arduous read is its relationship to its readership. Comic writers still operated under the premise that these stories were primarily aimed at children, who they apparently thought were idiots. The narration is thuddingly repetitive and artlessly expository, and every sentence that isn’t a question (but even some of those) ends in an exclamation point. Here’s an exchange between Masterson and his assistant at his “architecture business” (his words) after she stopped by his apartment one evening to “finish processing our current estimates”:

Susan: Your friend Harry Cleese seems a bit down!

Masterson: Yeah, well, he’s been having his problems lately!

Susan: Speaking of problems, don’t forget that your lawyer arranged for the people from child welfare to visit today!

Merging with Thor has caused Masterson all kinds of problems, including a bitter custody battle over his son Kevin. Then, a couple of panels down on the same page, is this inner monologue from Masterson (represented, of course, in a series of thought balloons):

I just can’t imagine losing him!

The people from child welfare are coming to see the kind of life I’m providing for him!

What if they disapprove? What if they think he’d be better off with my ex-wife?!

How could I ever accept being without him?!

Got to get my mind off Kevin, and concentrate on the job at hand!

The court will surely rule against me if my architecture business begins to slide!

You get the picture. It’s like everyone’s having a conversation underneath some roaring helicopter rotors. What little pathos may have come from an already clunky line like “How could I ever accept being without him?” is utterly undercut by that ghastly interrobang. And while we’re at it, the premise that Thor and Masterson were forced to share a body (and presumably their consciousnesses) is never explored in any depth or employed for anything other than to contrast the (hu)mundanity of Masterson’s plight with the divinity of Thor’s.

But the primary point is that this patronizing narrative style clogs the flow of the story, and doesn’t just do it occasionally. It’s all like this. Just flip through any Marvel omnibus featuring issues from the ‘60s and you’ll see a shocking amount of text for a medium with such a prominent visual component.

This gaudy proliferation of hand-holding text stems from what’s referred to as the “Marvel method,” a process originally motivated by narrative economy. In Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, Sean Howe describes Stan Lee’s philosophy behind their practice of distributing outlines of basic plots (concocted by Lee and Jack Kirby). Artists then had to draw these plots out in full so that Lee could insert dialogue and narration, which was how they produced all their titles at the time. According to Howe, Lee was emphatic that “every word… should move the story forward.” But the result, as Borenstein puts it in Marvel Comics in the 1970s, is “a process that looks ill-equipped to produce psychological nuance.” Subtlety was limited by the factory-like nature of the method, meaning that distinguishing individuality was inevitably excised. Instead, what we’re left with in terms of depth is Eric Masterson’s lament, as he falls from a building, and a fitting epitaph for early Marvel: “I… don’t know if this crazy plan is gonna work—but I don’t have a surplus of options!”

Borenstein examines the work of five Marvel Comics writers, but I’m going to focus on the example of Steve Englehart, as one of his most innovative contributions is the perfect counterexample to the simplicity of Thor: The Black Galaxy Saga.

Englehart accomplished a lot during his tenure at Marvel. According to Borenstein, he “turned Captain America from a failing title with limited appeal to a bestselling and timely comic,” and he helped craft some indelible runs of The Avengers and The Defenders. He was also a pot-smoking, astrology-loving conscientious objector who, along with artists Jim Starlin, Frank Brunner, Al Milgrom, and Alan Weiss, would take LSD and tool around Manhattan in its Taxi Driver era, pulling stunts like “traips[ing] by a security guard and wander[ing] through the World Trade Center while it was being built.” The gang saw Disney’s Alice in Wonderland at Lincoln Center, which inspired Englehart and Brunner’s psychedelic Doctor Strange run. They were, essentially, incorporating the countercultural movement into their work.

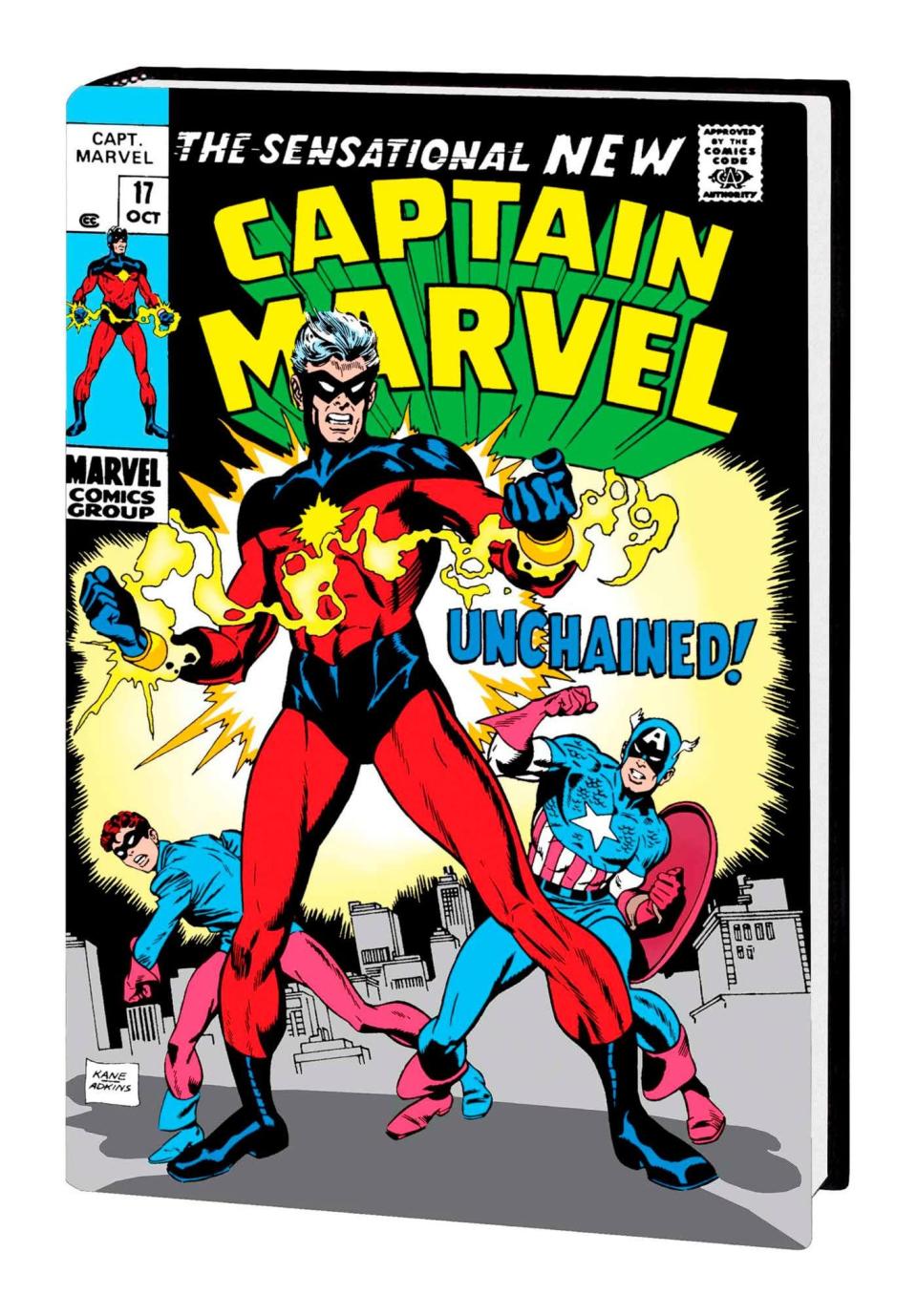

But when it comes to Englehart’s extension of comic possibilities, I want to focus on his two-year stint on Captain Marvel. The first Captain Marvel was published by Fawcett Comics in the ‘40s. Captain Marvel was actually a young boy named Billy Baston who could shout the word “Shazam” (which is, believe it or not, an acronym for the mythological mishmash of “elders” who grant Billy his powers: Solomon, Hercules, Atlas, Zeus, Achilles, and Mercury) and transform into an adult Superman-like superhero named Captain Marvel. DC sued Fawcett for copyright infringement, claiming Captain Marvel was stolen from Superman (which it kind of was). Fawcett then stopped publishing the title in 1953, leaving room for Marvel to swoop in, publish their own Captain Marvel in 1967, and because the moniker contained the company’s name, easily secure the trademark as soon as Fawcett’s lapsed. In the ‘70s, DC ended up licensing the character from the company they’d sued, but because they could no longer use Captain Marvel, they published the new version as Shazam! The point is that Marvel only launched their own Captain Marvel because they coveted the trademark.

$73.10

amazon.com

The reason I mention its litigious origins is to illustrate how far the comic book form had progressed within Marvel itself—how a money-grab could evolve into something much more interesting and artful. Marvel’s Captain Marvel was named Mar-Vell (I know; don’t get me started) and came from an alien race called the Kree. After passing through a number of hands and canceled titles, Roy Thomas and Gil Kane (the creators of Adam Warlock, played by Will Poulter in the Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3) “modernized his costume” and brought in Rick Jones—a non-superpowered guy whose life was saved by Bruce Banner—as Mar-Vell’s sidekick. At some point, Mar-Vell and Rick Jones become “molecularly bonded” while Captain Marvel was stuck in the Negative Zone. Because of this, Mar-Vell can clap his armbands together and switch places with Jones, wherever he happens to be, for three hours. Thomas, Borenstein notes, by employing a body-switching device, was consciously paralleling this new version with Fawcett’s original (instead of shouting “Shazam!,” Rick had to clap together his “Nega-Bands” to become, in a sense, Mar-Vell), but there’s a significant difference: “Billy Baston and the ‘World’s Mightiest Mortal” are simply different manifestations of the same consciousness, while Rick Jones and Mar-Vell each have well-established separate identities before they are forced together.”

The latter situation, though, is exactly like Thor’s “merging” with Eric Masterson. Masterston, like Jones, was a regular person introduced earlier, but the result is much more Shazam-like. When Engelhart took over the Captain Marvel series, he used the notion of bonded identities in much more provocative ways. For instance, Jones and Mar-Vell are also linked in their minds, so even though they have to switch places every three hours, they’re always able to communicate with one another. Jones is a “budding rock star” whose bandmate gives him a pill of “vitamin C”; meanwhile, while bored in the Negative Zone waiting to switch back, Jones takes what is clearly meant to be a hit of acid. The problem is, the pill also affects Mar-Vell, who’s on his way to the moon, and “soon he is completely incapacitated by the disorienting visual imagery and debilitating physical sensations coming at him.” Imagine tripping balls without knowing it while in outer fucking space.

Mar-Vell comes out of the experience with a new understanding of his shared consciousness with Jones—which, yes, is the typical post-trip sense of oneness with the universe: “We’re more than the same person! We’re the sum of our parts—and then some!” Consider how radical this was. At the time, the Comics Code Authority—a very real (despite sounding like a villainous organization from a comic) panic-driven association formed in the '50s by parents worried about depictions of violence and sex—still dictated appropriateness in the industry, though it no longer wielded as much power as it did in the first two decades of its existence. It’s still surprising that Englehart got away with a story that basically promotes the cosmic benefits of LSD. Furthermore, the exploration of selfhood via twinned consciousnesses and the power of psychedelics is a far cry from the days of Eric Masterson worrying about making it home before the welfare people arrive to investigate how he’s providing for Kevin.

It seems a minor development, especially to 21st-century minds, so accustomed as we are to deep meditations on any subject coming from any source—but these kinds of innovations, the ones made by artists and craftspeople working within larger hierarchies and corporate mandates, are just as significant and worthy of scholarship as the brilliant strokes of singular geniuses. The expansion of comics from the funny pages to scholarly journals doesn’t happen without them, just as the deepening of any art form requires, yes, brash iconoclasts, but also—and mostly—working artists whose contributions are small but mighty.

Borenstein traces the influence of Gerber, Englehart, and company on Chris Claremont, who wrote The Uncanny X-Men from 1975 until 1992, essentially bridging the gap between the ‘70s developments into the comic book’s rebirth in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Claremont gave his characters a similar kind of interiority—easy to grasp, but still deeper than mere archetypes—as his colleagues, playing with the contrast between their inner and outer lives. If Lee and Kirby’s creation of the X-Men stemmed, in part, from the civil rights movement, it was Claremont who deepened the themes from what were initially some very simplistic metaphors. His “Dark Phoenix Saga” run remains one of the most beloved in Marvel’s history. Moreover, Claremont made the X-Men a megahit (the first issue of a revamped X-Men in 1991 is still the best-selling single issue of a comic ever, topping eight million copies), which meant his style was greatly influential.

Mostly, though, the legacy of the ‘70s writers was carried on “outside of Marvel,” with Gerber, Englehart, Starlin, and Moench all leaving the company by the early ‘80s. Independent comics were on the rise, and icons like Will Eisner and Harvey Kurtzman were defining a new spin-off of comics: the graphic novel. In the early ‘90s, DC launched Vertigo, an imprint created to publish more adult-themed titles, and in 1992, Art Spiegelman won a special citation Pulitzer Prize. The sophistication of comics was complete.

$48.70

amazon.com

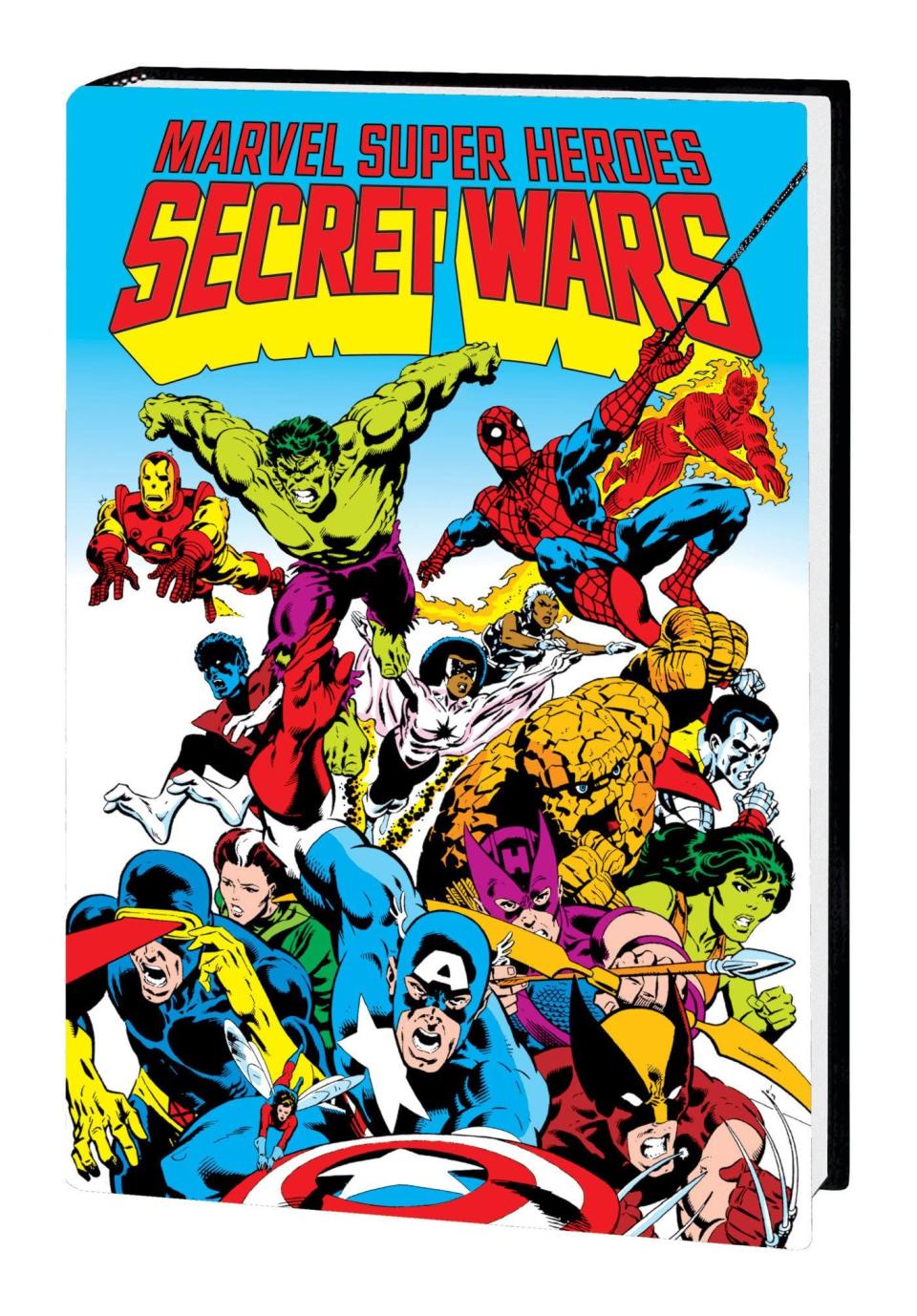

Meanwhile, Marvel in the ‘80s focused much of its attention on the spectacle of the major crossover event, beginning with Secret Wars, which involved every character in the Marvel Universe and was motivated by a Mattel toy line and role-playing game. Although much less artful and more brand-oriented than some of the work discussed here, Secret Wars was a huge success and nevertheless established the crossover as one of the greatest comic book conventions. The incredible ascendancy of the MCU owes much to Secret Wars (Marvel Studios is, indeed, organizing all of their Phase 4 and 5 films around an eventual Avengers: Secret Wars movie, but the one they’re doing is Jonathan Hickman’s run from 2015, which obviously pays tribute to the original ‘80s version, but also makes for a much, much better book).

The influence of the Marvel writers in the ‘70s is much harder to trace than, say, a much-hyped affair like Secret Wars or a singular achievement like Maus—which is a testament to Borenstein’s intelligence—but what they added to the history of comics is important, and now, with Marvel Comics in the 1970s, we can begin to correct the ledger.

In the early ‘70s, two paleontologists proposed a theory that sounds like it could have come from the pages of a Marvel comic: punctuated equilibrium. Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge posited that rather than the constant change and instability suggested by Darwin’s evolutionary theory of natural selection, certain shifts occur much more suddenly, while other times no major developments arise for centuries. Gould, in his gargantuan, nearly 1,500-page book The Structure of Evolutionary Theory, presents as foundational to his thesis “the central fact of the fossil record… geologically abrupt origin and subsequent extended stasis for most species.” This sounds like the kind of explanation you can imagine Professor X providing for the X-Men’s mutations (though of course the real explanation is pure narrative economy: it saved time that their powers required no backstories).

I have no idea how valid Gould and Eldredge’s theory is, but I do know that this is how we tend to construct our narratives of cultural history. We want to assign large portions of credit to singular talents who sporadically dot the timeline, while the contributions of the rest are flattened. Obviously, this isn’t a remotely valid approach to art history, but it’s a temptation we find difficult to resist. “Every song is a Beatles song,” we say, and it’s neat and it’s catchy and it’s easy to understand. But the truth is merely this: every Beatles song is a song. It’s a statement so obvious, so tautological, that it’s pointless to even make. Those kinds of truths don’t drive sales and they don’t work as taglines on posters, but reality’s banality is no justification to replace it with a fascinating fake.

The iconoclastic genius view of history reduces the story of human life to a survey course designed by sycophants. There are so many of us; there have been so many of us. Our history is not a clean timeline with occasional disruptions, but rather something much more like the Marvel Universe. Not in its supernatural storytelling, but in the philosophy of its interconnected construction: a piecemeal, slowly accumulating mass, the individual additions nearly indistinguishable. Or maybe they only become noticeable when you realize that the mass has moved, somehow, even though you didn’t discern any movement, the way looming clouds imperceptibly overwhelm a once-clear sky.

You Might Also Like