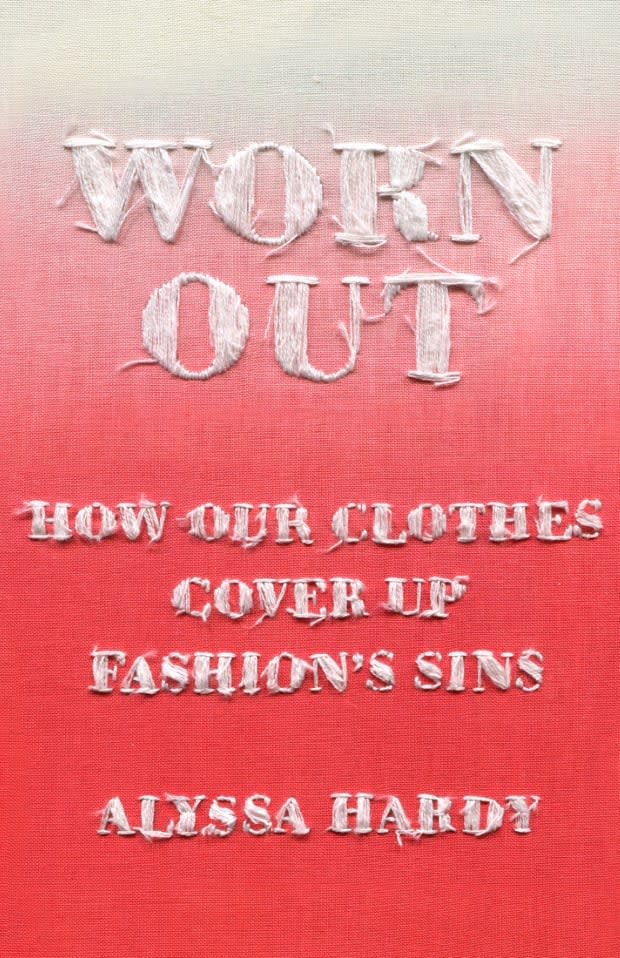

'Worn Out' Tells the Story of Fast Fashion's Fall From Grace

Former "InStyle" and Teen Vogue editor Alyssa Hardy spares no detail in her new book that reveals the dark underbelly of our current clothing binge.

If you're to take but one morsel away from Worn Out, Alyssa Hardy's new book that examines the dark underbelly of the global apparel industry, it's that, despite its flaws, loving fashion is not the problem. It's the way we consume it that can be.

After all, Hardy — whose byline you recognize from her editorial tenure first at Teen Vogue, then InStyle — is a fashion lover, first and foremost. She writes about the business with a glow that only true, unadulterated adoration makes possible. Which is what makes fashion's secretive, horrific labor and marketing practices so difficult for her to swallow.

While Hardy's first official fashion job was at her local mall's Abercrombie Kids, where the manufactured cinnamon scent of Auntie Anne's wafted nearby, she truly got her start at 18, when she moved to New York City for college and spent evenings traipsing around "The Tents" in Bryant Park — before, she says, fashion week became the spectacle it is today.

Much has changed in fashion since then, namely the ways in which we buy clothes. We've gotten more hungry for all that's shiny and new, and that continues to wreak dangerous havoc on the marginalized communities tasked with making more, more, more by the minute. This is where Worn Out comes in: The book reveals all the many ways the fashion industry works to actively cover up and perpetuate climate change and labor justice. Even more importantly, though, "Worn Out" gives a valuable platform to women who have experienced abuse, sexual assault, wage theft and illness within the confines of the factories that make our clothing, and enables them to share their stories in their own words.

"The workers are the only reason this movement is happening," Hardy tells me over Zoom. "They're speaking up, and it's very dangerous for a lot of them to do so. The only reason I know anything about this is because these women have said, 'I don't want to be treated this way,' and have spoken up about it. I hope more people support them and in whatever they're trying to fight for."

Ahead of the book's Tuesday, Sept. 27 release, we talked to Hardy about Worn Out, what she learned from writing this book and more. Read on for the highlights from our discussion.

Photo: Courtesy of The New Press

What first interested you about this intersection of fashion and sustainability?

I was at Teen Vogue for quite a while. I had been writing about a couple fast fashion brands, and because I'm a naturally curious person, I ended up doing more in-depth research into some of them. There was one, specifically, that I had written a story about, praising them, that had pretty serious accusations from the workers that they weren't being paid. And I was like, 'Damn, I just wrote a story telling young people to go shop at this brand.' I realized this was impacting the women who were making the clothing, who were experiencing all sorts of wage theft and abuse in their factories. My initial, really serious interest in this came from a little bit of culpability in sort of ignoring these issues.

From there, how did the opportunity to write and publish Worn Out come about?

At that second, I was like, 'Hey, I come from a working-class family. I want to make sure we're writing about workers.' Everyone at Teen Vogue was like, 'Yeah, sounds great.' It was a perfect place for me to write those kinds of stories. But eventually, I wanted to get more in depth, but I wasn't being given the resources to do that. So I started toying around with this question of, 'How do I get the resources to research this more?' I had talked to another fashion editor friend and she was like, 'Well, I'm writing a memoir and I have a great agent.' So, I spoke with her, and started writing a proposal.

I was really concerned about who was going to edit this book with me. Obviously, there's two different sides of it. I wanted somebody who could understand fashion, but that wasn't super important — it was way more important to me to work with somebody who could understand labor and social justice. The New Press is a very social justice-focused imprint. They have amazing books, obviously, and I knew they were going to treat this and these workers' stories with respect, and check me on the ways I speak about them, too.

You went into writing this book already being knowledgeable about the topic, but I imagine there were still elements of your research that surprised you. I, for one, was shocked to read about the "homeworkers" in Indonesia unknowingly working with carcinogenic materials. What's something new you learned about the fashion industry during this process?

I had a basic knowledge of a lot of these topics. What I knew of homework was from a story I had done a couple years ago. One of the luxury brands had been using embroiderers from Indonesia, and they were only paying them pennies. I had spoken to an activist at the time and they said, 'Some homework, especially in small villages, makes sense. However, the philosophy is that, until we get it regulated, homework is bad.'

Speaking to Ibu Linna, who's in the book, I learned just how much this type of work impacts their communities. It's everything. It's their traditions, and so they need to preserve them. But at the same time, we have these brands coming in and exploiting them on multiple levels — exploiting their wages, exploiting their labor and exploiting their children, putting toxic dyes into their water. And I had no idea that was happening. She was like, 'We need the homework, but we can't have our traditions exploited.'

This month, you were vocal in your criticism of Boohoo tapping Kourney Kardashian as its new sustainability ambassador. The conversation reminded me of a portion of Worn Out in which you discuss how celebrities can obscure the exploitation going on behind the curtain of big-name brands. What can you tell me about that dynamic, and how is it harmful to the industry at large?

I tried to touch on this a little in the book, but I love celebrities. I am fully influenced by so many of them. I get it. I think it's a very powerful thing. But when they use their influence in certain ways and then go, 'It's not my fault.' It's like, 'Well, yeah, it is your fault. You know your influence, you know the money you're making off of this.'

With the Boohoo thing, specifically, I'm sure there are upcycled jackets and tops, and that's great — but what happens when Kourtney Kardashian comes in and says, 'I'm working with this brand to make them sustainable,' when she is, in fact, not doing that? She's making a couple of pieces on top of the millions of other pieces they're making marginally more sustainable.

In my opinion, I don't think consumers need to be experts on sustainability. I mean, they should have knowledge of it, but we can't expect consumers to be experts on the inner workings of every aspect of sustainability. So when you have somebody who's trusted — I don't know how trusted she is, specifically — that way, saying, 'This is sustainable,' it puts that stamp on the entire brand. Meanwhile, they're not. Because, one, consider the amount of clothing they're making, and two, there's labor issues with their workers. If either of those are the case at all, then your brand's not sustainable. I think they do a lot to obscure the messaging, and the brand that's actually doing the work to make upcycled leather jackets is going to get completely overshadowed by these $6 jackets or whatever they cost. And I'm sure Kourtney thinks she's doing the right thing — I mean, I don't know that when this happens, it's always sinister, but the result is.

Photo: Courtesy of The New Press

Elizabeth Cline, whose work you reference in Worn Out, has famously said that the retail industry needs fewer "ethical consumers" who hold themselves responsible for fashion's climate problem and more "consumer advocates" who hold brands — which are the largest pollutants — accountable. How can people start to hold those companies accountable for their contributions to the climate crisis, while still being responsible consumers themselves?

The number-one thing I want everybody to realize — and this is in my opinion, I guess, but I think it's the truth — is that it's the brand's fault. First and foremost, they take most of the blame. They’re the ones making money off exploiting people and exploiting the planet. But I think it's great that individuals want to help and want to fix this problem.

As consumers, I hope that we look outside of just consumption as a way to fix things. It's great to say, 'I'm only shopping sustainably.' Of course, that can go very far. But I think the more important thing is vocal support. There are so many protests around the world from workers who are being exploited by various companies. Right now, for example, workers are talking about how Levi's hasn't signed the Bangladesh Accord, so a lot of them are protesting. These companies, they give a shit when people are like, 'Actually, I know you're exploiting people, and I'm going to talk about it on social media.'

After 2020, H&M redid all of its sexual harassment training in its factories, not because they wanted to — they did it because people were like, 'This is sick that women are saying they're being abused in your factories and you don't care.' People should recognize that their voice is really important. In the U.S., there's bills that can be supported now. You can call your Congressperson and say, 'I want you to support the FABRIC Act,' which is a labor bill. People can use their voice. It doesn't have to just be, 'Oh, I'm going to buy only secondhand.' That's great, but there are other ways.

Speaking of which, both the FABRIC Act and SB 62 were huge wins on that front. What's next for fashion policy on a state or federal level?

I think that the 'Made in America' myth is so deep. People quickly forget that what happened at the El Monte sweatshop was only in the '90s. This is such recent history. Of course, we know there's wage theft throughout every industry in the country. But for some reason, a 'Made in America' label in fashion is a stamp of approval, probably just because we want it to be. There are probably innocent intentions there, for the most part.

We just want to eliminate wage theft. It's gross. It sucks. A lot of brands do it, and they need to be liable for it. They can't just keep saying, 'Well, the factory is doing this and we don't know.' That's too bad. It's your factory. You need to be paying attention to what's happening in your factory. Even if it's the truth that you don't know, you should know.

The other piece of it that's interesting is that labor bills will offer reshoring tax breaks for brands to bring their production here. We know it's extremely expensive to produce in the U.S. That's real. Giving incentives for brands to do it where it can be regulated and done properly could be a way in for so many young designers who just want to be closer to their factories.

That's what I love about the FABRIC Act, specifically. And like I said, anybody can call their Congressperson. You don't have to be in California or New York; this is going to impact factories in Texas, in Washington State, in North Carolina. Anybody can call and say, 'Hey, I want to have good-wage jobs in my community. I want to bring women-led manufacturing jobs to where I live.'

When you think about the future of ethicality, sustainability and fashion, where do you imagine it going?

Regulation is going to be the way we fix this. The brands aren't going to do it on their own. We clearly have issues in terms of how we consume that are pretty much beyond repair. Obviously, awareness is great, but just judging by the way it's going, it doesn't seem to be slowing in any way. And projections say it's only going to grow. So I think the only real way we can change this is by regulation and having brands get on board with these regulations, too, saying, 'This is what's actually practical for business, and this is how we can help other brands.' The brands that are causing the most problems aren't going to do it on their own. Us, as people, should plan on supporting that when it comes up.

Never miss the latest fashion industry news. Sign up for the Fashionista daily newsletter.