'The world doesn’t care': Homeless deaths spiked during pandemic, not from COVID. From drugs.

LOS ANGELES – It happened nine times.

Sometimes it would be after spotting someone shooting up heroin and suddenly losing consciousness. In others, it would be after shouts in the dead of night that someone was dying of an overdose.

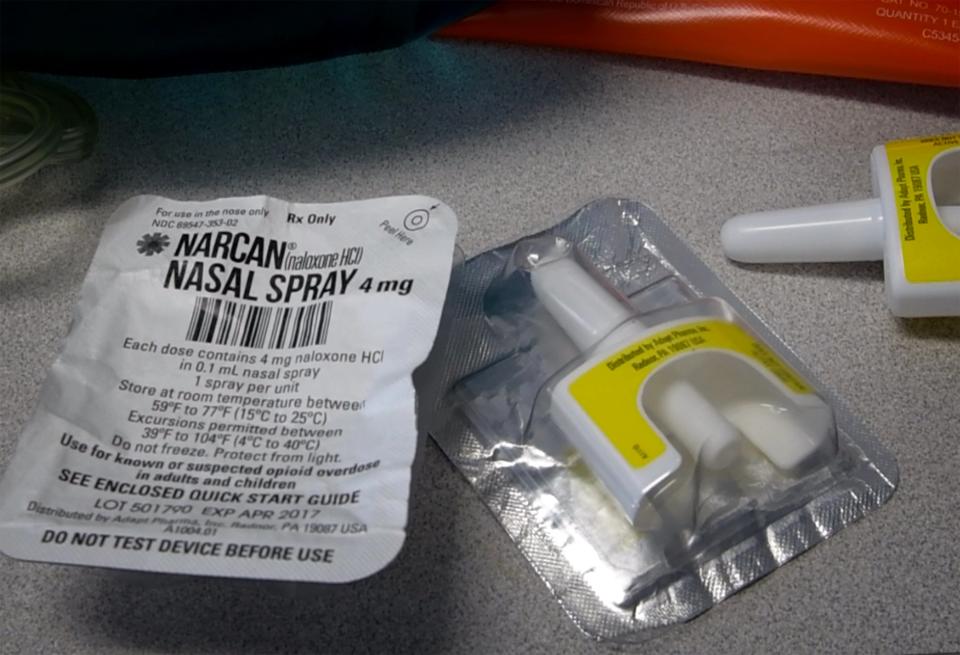

Each time, Fredrick Mitchel, 58, pulled out Narcan, the medicine that can undo an opioid overdose, and tried to save a life.

“I’ve watched the breath of life return to people,” said Mitchel, who has struggled with drug use himself. “People don’t realize what is happening and sometimes it feels like the world doesn’t care. It’s traumatic.”

Mitchel is still haunted by the friends and neighbors living on the streets of Skid Row whom he couldn't save, those who died during the COVID-19 pandemic – not from the deadly virus but from drug overdoses. Many drugs probably were laced with fentanyl, the potent opioid that fueled a record number of overdoses in the U.S. last year, according to federal data released earlier this month.

In Los Angeles County, nearly 2,000 homeless people died during the first year of the pandemic in 2020, an increase of 56% from 2019. Of those, 715 were from drug overdoses.

LA was not alone. Those experiencing homelessness have been dying in greater numbers across the nation throughout the pandemic, reaching new highs in several U.S. cities, according to a USA TODAY review of data in 10 U.S. cities and counties with some of the highest numbers of homeless people. And drugs, not the virus, are largely to blame, the data shows.

“This hasn’t gotten better. It’s only getting worse,” said Bobby Watts, CEO of the National Health Care for the Homeless Council. “To see people living on the streets, living in these conditions, then to see them dying like this when we live in such a wealthy country – it wounds the soul of our nation.”

TRAGIC RECORDS: More than 107,000 Americans died from overdoses last year. This drug is behind most deaths.

Drug overdoses play outsized role in homeless deaths across U.S.

Throughout the country, homeless deaths spiked during the first two years of the pandemic. But in some areas, not a single death was attributed to the virus itself.

San Francisco saw more than twice as many homeless people die in the first year of the pandemic compared with the four years before. About 54% of these deaths were from drug overdoses – a proportion that hadn't been seen in previous years. Not a single death was from COVID-19.

A similar spike erupted in Portland and the Seattle area.

In 2021, the second year of the pandemic, at least 71 homeless deaths in the Seattle area were from overdoses, a number public health officials said had never been so high.

A record 126 homeless people died in Multnomah County, Oregon’s most populous county, which includes Portland. Methamphetamines were a factor in nearly half of the deaths, a record since officials began tracking homeless deaths a decade ago. No deaths were attributed to COVID-19.

Christopher Madson-Yamasaki was among those deaths.

The 26-year-old’s mother, Hope Yamasaki, said her son had struggled to find help before he was found dead in February 2020 in a tent.

Yamasaki said her son, who was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder – a chronic condition in which someone experiences symptoms of schizophrenia and disorders such as depression – spent years in and out of programs.

“I can’t even count. We went back and forth to inpatient,” Yamasaki said. “He was kicked out of rehab because of mental health problems and kicked out of mental health programs because of drugs.”

Other U.S. cities similarly saw spikes in deaths among homeless people:

• San Diego saw 434 deaths in 2021, an increase from 344 the year before. A midyear report showed a 149% increase in deaths from fentanyl.

• Indianapolis saw 166 people die in 2021, the most in at least six years.

• The Denver area saw deaths spike during the pandemic with 269 reported in 2021, nearly half from overdoses.

• Washington, D.C., saw 180 homeless people die in 2020, a 54% increase from the 117 who died in 2019. Up to 80 people died of intoxication.

• The Las Vegas area saw deaths spike to 186 in 2020, about 30% of which were from substance abuse.

A tale of two cities: Los Angeles and New York

Data that tracks both the number of people experiencing homeless and those who die is difficult to verify. Many U.S. cities don’t make such data public, and the ones that do note the counts are probably severely lower than reality, especially in cities such as LA where much of the homeless population lives outdoors and not in shelters.

But publicly available data shows New York’s homeless population is the highest in the country, at about 70,000 people. Los Angeles follows with more than 66,000. Despite that, the number of deaths in both cities at the start of the pandemic were vastly different.

Los Angeles saw 1,988 homeless people die from April 2020 to the end of March 2021. In a similar period – July 2020 to the end of June 2021 – 640 people died in New York, about a third of what LA saw.

But in both cities, drug overdoses increased by about 80% and were listed as the leading cause of death.

Experts note the differences in mortality probably is the result of two key factors: Los Angeles has a much older homeless population and many live outdoors, which makes it harder to access services and health care.

In fact, at least 252 homeless people in Los Angeles County were found dead on sidewalks and another 56 in tents, 101 on streets and alleyways, 95 in county parks and 25 on railroad tracks or train platforms in that time period, according to an analysis of data obtained by USA TODAY from the Los Angeles County Coroner.

BUG INFESTATIONS, TENT-LINED STREETS: California's homelessness crisis is at a tipping point. Will a $12B plan put a dent in it?

HOMELESSNESS IN LA: Homelessness is biggest problem facing Los Angeles, residents say, and it's projected to get worse

“It’s an apples-to-oranges comparison,” said Gary Blasi, a professor emeritus at UCLA law school who specializes in homelessness and evictions. “You are 12 times more likely to be housed in a shelter in New York. And simply being inside allows so much, from a clean shower and good night’s sleep to a small sense of stability and relief from that hopelessness.”

Experts say Narcan, safe-injection sites needed to halt overdoses

Life shut down during the first stretches of the pandemic in the spring of 2020. Homeless outreach teams weren’t patrolling the streets as often, which made it much harder to acquire hygiene necessities, food and lifesaving tools such as Narcan.

Businesses and public facilities, including libraries, were closed, which blocked access to computers and bathrooms. Health care facilities and substance-use services were focused on and wary of COVID-19, which meant homeless people had less access to treatment.

“When you look at it, saying COVID wasn’t to blame for deaths is an oversimplification,” said Ciara DeVozza, who helps lead outreach in the Skid Row community for The People Concern, one of the largest homeless relief organizations in the Los Angeles area. “There was a lack of services and help for some of the most vulnerable.”

DeVozza’s team regularly walks the Skid Row area, stopping by tents lining the streets and offering help. Her team also hands out packs of Narcan, teaching those living on the streets how to use the lifesaving drug in case they or a neighbor experiences an overdose.

Before the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said not enough was being done to make the drug readily available. Los Angeles County Health Services has been working to distribute more than 100,000 doses of naloxone, a drug commonly known as Narcan, and says it has helped reverse more than 5,000 overdoses.

DeVozza and other experts say greater access also is needed to medications treating opioid addiction and more cities need to launch safe-injection sites such as those in New York City, facilities that allow drug use and provide clean needles and other materials.

HOMELESS TARGETED: As national housing crisis spirals, cities criminalize homeless people, ban tents, close parks

But some homeless care facilities in the Los Angeles area and across the country are resistant to these tactics, saying it allows increased drug use. Michele Steeb, who worked for 13 years at a women’s crisis center, and Thomas Wolf, a recovering heroin addict who was homeless, wrote an opinion column in USA TODAY last year decrying the idea of allowing safe-injection sites in California, saying it would benefit drug dealers and wouldn’t help the substance abuse epidemic.

Experts have pushed back on that argument. Blasi said homeless people are far less likely to overcome drug addiction or mental health conditions while living outdoors, so housing has to be the top priority. Overdose prevention saves lives for those still on the streets, he said.

CALIFORNIA CROSS-ROADS:Is California, one of the bluest states in the US, at a turning point over crime, homelessness?

"This may sound trite, but there's very little evidence that any program can successfully treat either severe mental illness or addiction while people are on the street," Blasi said. "It's just impossible to deal with on the street. So frankly, I don't think there's much that can be done until a person is housed."

'I couldn't understand how I reached that point'

Mitchel said he hung out with the wrong crowds growing up, falling into crime and heavy drug use. He bounced around from Tennessee to Ohio before finding his way to California. But it wasn’t long before the arrests piled up, and he landed in prison for five years.

He tried rehabilitation programs, began working for a ride-share company and started college. But he could never fully cut his drug ties, which ate away at his life and pushed him onto Skid Row, a neighborhood in downtown Los Angeles that houses a large share of the area’s homeless population.

Once there, he felt there was no way out, he says, and the feelings of depression and hopelessness fostered more drug use. Mitchel overdosed on heroin in 2021.

“I couldn’t understand how I reached that point,” Mitchel said. People don't understand that many homeless who use drugs "aren’t doing it because they want to get high. You’re in a crisis. You’re depressed. You’re in pain. They don’t always realize this choice could be life or death because it feels like an escape. And in the moment, it feels worth it.”

Mitchel got multiple packs of Narcan from The People Concern while living on Skid Row. Without it, he says, at least nine people would probably be dead. Ten if he includes himself.

He says he is recovering from his addiction and moving into a place of his own next month. Mitchel hopes to share his story and help others struggling with drug addictions and homelessness.

"This is just the beginning of a new life," he said. "This is a new chapter."

Contributing: The Associated Press

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Drug overdoses led to sharp increase in US homeless deaths, not COVID