What Words Can I Say to Declare That I’m Gay?

Gay. Gay. Gay. I’ve never wanted to say it more.

Florida’s infuriating “Don’t Say Gay” law has given new power to an old word. Just look at the T-shirts and protest signs: “#SayGay” is the new “We’re here. We’re queer.”

The law, which prohibits discussion of sexual orientation and gender identity in a manner that is not “developmentally appropriate,” is deliberately, devilishly vague. But it has made me think about the words I choose to use and not use—about the good words and the bad.

As a children’s author and the father of twins, I excel at censoring myself. The first book I wrote, The Name of This Book Is Secret, I put the word damn in it. A harmless word, I thought. Who could object? It stayed until the Scholastic Book Club demanded I take it out—or else they’d take my book off their very lucrative list. That was 12 titles ago, and I haven’t included a single damn since. Never mind an asshole or even a bitch.

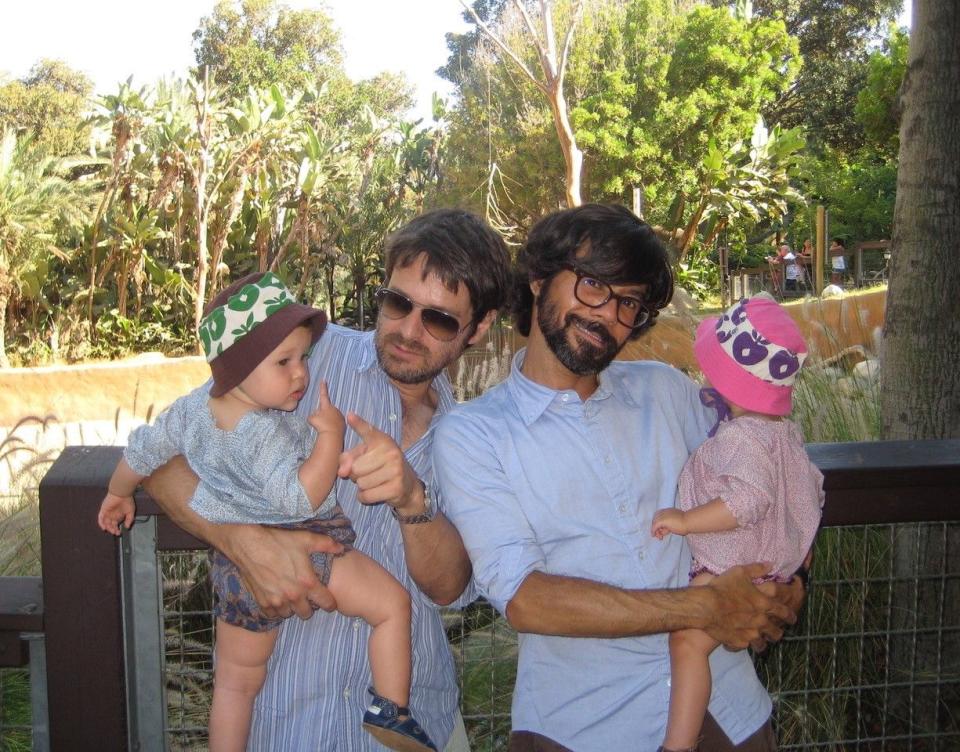

As for our family, I’d originally envisioned a more bohemian lifestyle, with midnight dinners and toddlers who swore like sailors. But that fantasy ended as soon as the twins could talk. As gay dads at a time when gay families were still relatively rare, my husband and I felt the pressure to be model parents. No four-letter words in our house! We lasted longer than I would have thought possible. In third grade, our kids still thought the F-word was fart.

Alas, they grew up. Now that the twins are teens, the household dynamics have flipped. Today, they are the enforcers of correct speech, and we parents the perpetrators of all linguistic offenses. These new offenses are of a different order than the old. When we swear in front of them, the kids shrug. “Oh, fuck!” is perfectly permissible. It’s a failure to remember a recent pronoun change or anything that they perceive as a slight on a marginalized group that will get us indicted by our in-house team of prosecutors.

“You can’t say that!”

Our kids have berated me numerous times, but never as vehemently as when I used a word that rhymes with psych.

“You can’t say that, Daddy—that’s the D-slur. It’s offensive!”

They said only a lesbian could use it. Just like only Black people could use the N-word. No exceptions.

“But I’m gay!” I protested. “And the word was reclaimed. Like queer was reclaimed. Haven’t you heard of Dykes on Bikes? Besides, I practically was a lesbian for a while. Well, except that I never watched football.”

My co-father verified that back in the hoary old ’90s, half my friends had been women-loving women.

“They called each other the D-slur all the time,” I said. “Me, too—I thought of myself as one of them.”

I told my kids about the day I went to see Go Fish, the 1994 indie comedy about a group of young lesbians. Enthralled, I’d turned to the friend sitting next to me: “Finally, a movie about us!” My friend raised an eyebrow: “You realize this cast is all female?”

My kids laughed as I described how my face turned red. They love, categorically, any story that involves a parent being embarrassed. But I still wasn’t allowed to use the D-slur. Unless this was my way of announcing that my pronouns were she/her and that I really was a lesbian? No? Then, sorry, I did not get a pass.

“Well, what about the F-slur—do I at least get to use that?” I asked, referring to a word that rhymes with—oh, hell, I’ll just write it.

Faggot.

If my social media feeds are anything to go by, most gay men live in packs. Twinks and bears, at brunch or tea dance, they stand together, pec to pec, forever grooving to the same secret playlist. No shirts needed.

Sadly, it isn’t that way for all of us. For whatever reason—shyness? bad luck? bad breath?—I’ve never had as many gay guy friends as the algorithms on my phone seem to expect.

On the other hand, I have a number of straight friends who have significantly more gay friends than I do. These friends of mine are, you might say, culturally gay—in much the way I was once culturally lesbian.

At one time or another, I’ve heard most of my gay-ish straight friends utter the word faggot, or at least its shorter sibling, fag. Of course, my friends, being my friends, don’t use these words as pejoratives. To them, fag means fab. Just as to me, dyke has always meant pretty darn cool.

Until recently, I never thought to complain.

I came of age in the 1980s, meaning that in addition to being old, I am comfortable with a certain degree of cynicism and hypocrisy—or as we used to call it, irony. For me, as for any blithely self-regarding Gen Xer, the temptation is to dismiss my children’s Gen Z concerns as loutish, literal, and, sin of sins, unnuanced.

But if I’m being honest, I think the kids are onto something.

It makes me squirm when I hear a straight person call someone a faggot, no matter how many gay friends this person may have. Not long ago, a friend joked about how she needed me and my husband to be her “bodyguard queens”—to protect her at some party she was going to. I didn’t say anything at the time, but her joke didn’t sit well with me. It was a step above the icky, patronizing tone of the woman who asked me in all seriousness to be her gay best friend. But only a step.

Someone who had the right to use the word faggot? My medieval history professor, John Boswell. One day, in my freshman year of college, he arrived for a lecture with his head covered in bandages, his arm in a sling. A small, boyish man, he was clearly in pain, but he remained standing.

“They called me faggot,” he told 300 stunned undergraduates. “Then they left me for dead.”

Soon after, he published his study of early Christian commitment ceremonies—Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe—helping to lay the groundwork for the modern gay marriage movement and, ultimately, my own marriage.

Boswell died of AIDS in 1994—left for dead not by some townie gay bashers but by an entire nation indifferent to the lives of men who have sex with men.

I’ve been called a faggot more than once, in ways that no one would confuse with flattery. But the time I remember best, the guy using the word, well, he was me.

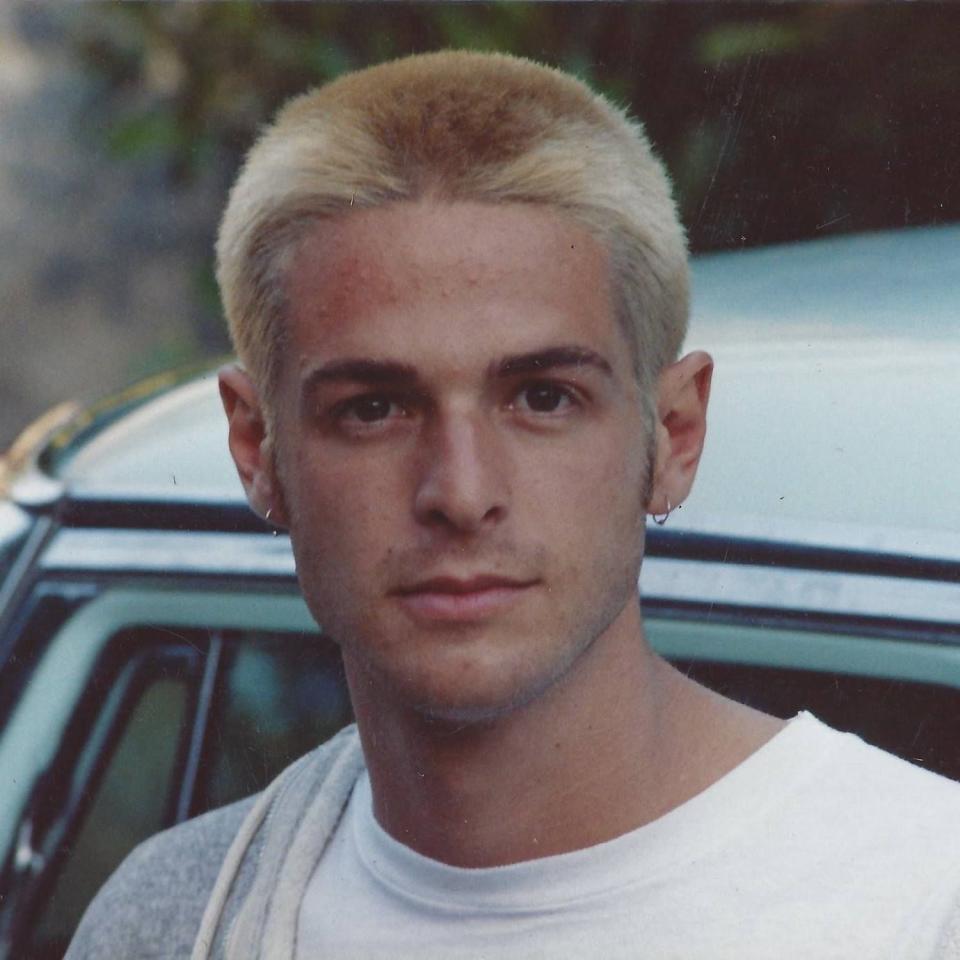

It was 1991. The Republican governor of California, Pete Wilson, had just vetoed a bill that would have protected gays and lesbians from job discrimination, and I was a graduate student at the University of California Irvine. Irvine is in Orange County, the Republican capital of California, and I blamed everyone I saw for what the governor had done.

Determined to stick it out, but also to stick out, I bleached my hair. I wore beaded necklaces and purple shoes. On my school bag, I placed a bright green sticker: “QUEER LIBERATION NOT ASSIMILATION.” And yet my appearance made scarcely a ripple.

Then, late in the fall semester, I visited the university gym with a fellow graduate student. Let’s call him Sam. Though straight, Sam had many gay admirers. He had this elusive, fawn-like quality that made you imagine chasing him through a forest. Or around a couch, as I’d heard another gay graduate student had done, to my chagrin. We’d only just started using the Nautilus machines when a very tough-looking—and very hot-looking—guy glared at Sam.

“Stop staring at me, faggot,” he said. “I’ll fuck you up if you keep checking me out!”

The threat was so unexpected that it took me a moment to figure out who was saying what to whom. Had Sam really been checking out the guy, or had their eyes locked accidentally? Was this angry gym bro projecting his own issues onto my friend? Maybe he had been checking out Sam.

Whatever Gym Bro’s motivation, his threat seemed real enough. Sam looked petrified.

I stepped between them, as if I were auditioning for the part of some new gay superhero.

“Actually, he’s straight,” I said. “I’m the only faggot here.”

I don’t remember Gym Bro’s response—I was so nervous, I was lucky not to throw up—but I confused him sufficiently to diffuse the situation. Nobody got hurt.

Calling myself a faggot in order to protect a straight friend from being gay-bashed—heroic, right? Bad word begets good deed. It makes for a nice story. Here’s the truth: It didn’t feel heroic at the time. I wasn’t taking a big stand for gay visibility, or even acting selflessly to help my friend. The thing making my heart pound—aside from fear—was shame.

Shame that, by the time I spoke up, I was checking out the package in Gym Bro’s shorts, more or less as he’d just accused Sam of doing. Shame that I had for weeks been fantasizing about what I’d find in Sam’s pants too. Shame that I was a homosexual, in other words.

I told Gym Bro that I was the faggot, because in my mind, I was the faggot. It was less an act of bravery than an admission of guilt. And that, not to put too fine a point on it, is very fucked up. I had no reason to feel guilty or ashamed.

Not long after the incident in the gym, I had a meeting with a student in my composition class. She was very sweet, very blonde, and very much not paying attention to what I was saying.

“Sorry, I have to ask,” she said, pointing to my ears, each of which bore a small gold hoop. “Isn’t one of those the gay side?”

“Yeah, but I couldn’t remember which,” I joked. “That’s why I had to pierce both sides.”

Her eyes widened. “But you’re not gay!”

“Yes. I am.”

“No.”

“Yes.”

She told me that she came from a super-small town and had led a super-sheltered life. “Once, in high school, I thought somebody was Asian, but they weren’t,” she said by way of illustration.

Our conversation emboldened me to come out to more of my students. Sometimes an earring, or even a sticker, isn’t enough; you have to say the words aloud. Otherwise, people choose your words for you.

If I could turn back time (hi, Cher!), I wouldn’t tell that guy in the gym that I was a faggot. I would say, “Don’t use that word, Gym Bro. And by the way, I’m gay.”

Nowadays, with school boards banning books by the dozen, it’s hard to keep up with all the things that can’t be read and can’t be said. As it turns out, while I was whining into my rosé about all the wokeness in my house, reactionary forces were gathering, ready to send this country back to a time when racism wasn’t talked about, trans kids suffered in silence, and homophobia had yet to be named. If the “Don’t Say Gay” bill proves anything, it’s that plenty of people still think gay is a bad word.

All the more reason to remember what the real bad words are.

You Might Also Like