I Won't Let My Child's Epilepsy Diagnosis Define Him

Provided by Stephanie Elliot

"That's not normal."

I looked at my mom and then at my ten-year-old son, who was sitting at the kitchen counter, doing homework.

My mom said it again. "What he's doing, with his eyes—that's not normal. He shouldn't be doing that."

"Mom, he's fine."

I had been telling myself this, trying to convince myself that my youngest child was fine, that this shift in him wasn't anything to worry about. It was slight, so slight at first we couldn't even pinpoint when it started, this loss of time, this moment or two when he would stop, sometimes mid-sentence, and lift his eyes slightly, as if he were grasping for words, searching his mind for his next thought.

"Mom," I said, "He's just thinking. He's trying to come up with his next words."

But when the school nurse called because Luke told his teacher he had a headache and then he vomited, I knew it was more than a momentary loss for words. It was something to worry about.

An immediate CT scan came up with nothing, but headaches continued and we still noticed Luke staring into space for short periods of time throughout each day. It was so slight you could turn your head and miss these episodes, but they were coming more and more frequently that we were concerned. I mentioned it to his teacher, who hadn't noticed it. "He always participates in class," she assured me. I mentioned it to his pediatrician. She noted it in his file but didn't have cause for concern. We chalked up the headaches to the late spring Arizona heat.

Related: What Not to Do If Your Child is Sick

Luke is our third child. The day he was born—almost two weeks past his due date— I stared in wonder at him and couldn't believe his eyelashes hadn't grown in yet when he'd lived inside me for nine and a half months. These days, when I whisper secrets to him, he listens intently, eyes wide, eyelashes so full and long, the kind that would "green" any girl into jealousy.

I've been sharing a huge secret with him since before he was even able to understand it, since before he could even communicate with me. It is this: I tell Luke that before he came along, I already had the perfect family. I already had a precious firstborn boy, and 18 months later, my princess daughter arrived. Had I been so selfish to want a third child? I didn't need another baby, and yet I wanted one. Him. We chose to have a third child. Luke was our gift. We wanted him, wholly and fully, we wanted him in our lives. Just because.

And now, there's something wrong with our gift of a boy.

Luke is brave. He's not sure what's wrong, and we're not sure what's wrong either. But we're all watching him closely, carefully. When he's counting arm lifts for his brother, he stops mid-count, and loses track, then can't remember what number he's on. He tells a story, then fades away for a few seconds, his eyes roll upward, and we say, "Luke, Luke,"…come back Luke…but he can't hear us, and it scares us, but we try not to show fear. And he tries to act like it doesn't bother him either.

One day, early summer, he and I lounge in the pool, our bodies plopped into the doughnut hole of round dollar-store floats, the sun warming our faces. I count to myself how many times Luke "loses space and time" because that's what we're calling it now.

He disappears from me eight times in one hour. An alarming amount.

These 'quirks' have been happening for almost three months. I'm desperate to figure out what's wrong with my little boy. And so I do what any logical person does these days. I go to Google.

I type in "kids staring into space" and just like that, our lives are changed forever.

I've found my answer.

Absence seizures.

My God. My child has been having seizures this whole time and I've done nothing. For three months, or maybe longer, I have let hell wreak havoc on my son's brain and I've done nothing to prevent this? The guilt, the regret, the fear—the discovery is all so overwhelming.

But then, almost immediately, I am awash in relief. I will get answers.

I spend hours reading about what my son surely must have, and I watch YouTube videos of other children who are doing exactly what my son has been doing.

Absence seizures. Petit mals.

Epilepsy.

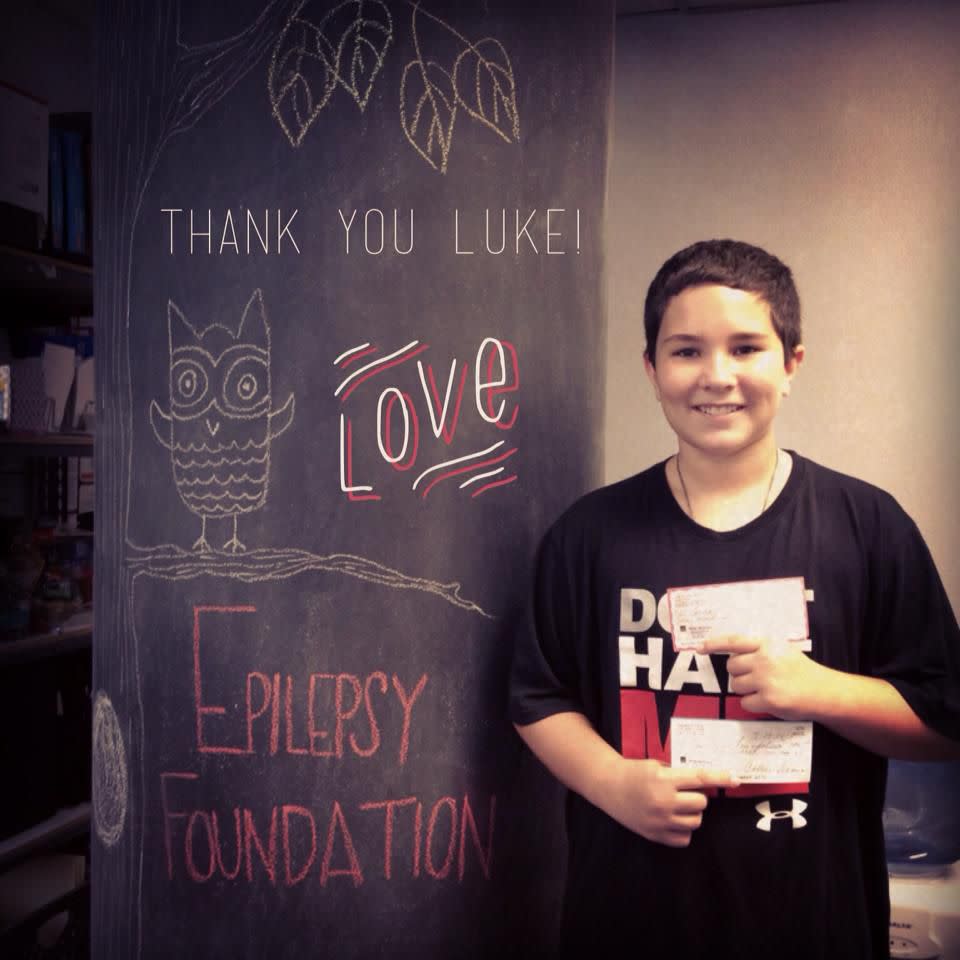

Provided by Stephanie Elliot

You would think having a diagnosis makes things better. It doesn't. There are EEGs where technicians force Luke to hyperventilate in order to make him have seizures. There are medicines that give him horrible side effects, turning his blood cold, giving him terrible migraines, making his arms and fingers tingle, and he vomits for almost five days straight. We are warned that there is a 70 percent chance he could have a grand mal seizure.

We are home with him, thank God, when he has his first full-blown grand mal seizure.

Related: How Epilepsy is Diagnosed

That evening, I knew something wasn't right. Luke looked sullen, sad. I asked him, "Are you in a bad mood because school is starting? Are you upset with your brother or sister?" He didn't want to eat dinner; he couldn't articulate what was wrong. I asked him to lay down with me for a bit, and then he wanted to play Chinese checkers with his dad and me. This was God intervening because never in his 10 years has he gotten both his father and me to play a board game with him.

The three of us sat on the family room floor and played Chinese checkers. Luke looked up, hesitated for a moment, and then fell to the floor. He began to seize. We were prepared and knew what to do…through his convulsions and tongue biting, the thrashing, and eye rolling. And through our fear. Again, thank God. We knew what to do.

Two-and-a-half weeks later, he has another grand mal seizure, this time at the end of the day, in class, at school. Again, thank God, I had prepared everyone on the school staff, and they also knew what to do.

More doctor visits, a 24-hour EEG and a hospital stay, a medication switch, and we are hopefully on the right path now. Still, there is worry. There is regret. This is a genetic disease. Somehow, my husband and I caused this to happen to our son. I feel guilty, as if I gave this to our son—the child we didn't need but so very much wanted. I regret that I can't protect him the way that I so desperately want to.

I watch him so carefully now. There's no locking the bathroom door. He can't take a shower without one of us being in the bathroom with him. I watch for clues that he might not be feeling well. When he's not near me, I yell for him, "Luke, where are you?" My need to protect him is fierce and maternal, like never, ever before. His teacher was there when he had his seizure at school. We talk every day to discuss Luke's well-being. She asked me, "Do you sleep at night? How do you sleep at night?" "That's the easy part," I tell her. "He's right here with me then. That's when I know he's safest." But I know I have to give him freedom, or I'll regret that too.

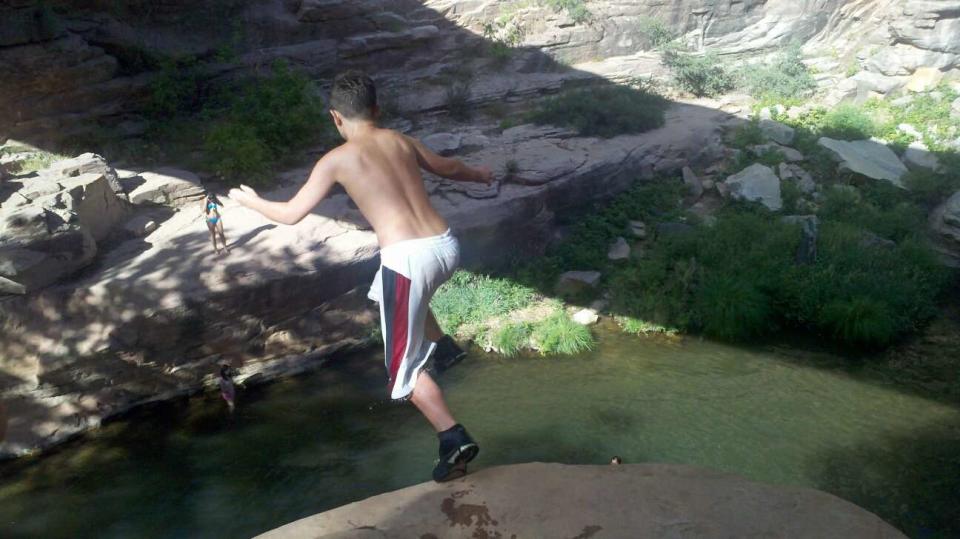

When all of this began, when Luke was first diagnosed and he started medication, our family went to Sedona for the weekend. We needed to get away together, to bond, to connect, to secure our family. We went to Slide Rock—a well-known tourist spot with natural rock formations and waterfalls. People climb up the rocks and jump from high above into the crisp, blue water.

Luke making the jump at Slide Rock. Provided by Stephanie Elliot

We climbed to the top of one rock formation, about thirty feet high, and watched as brave teenagers flung their bodies over the edge. Their screams and laughter could be heard from the bottom after they plunged into the water. All three of my kids looked at their father and me, asking permission with their eyes, not actually using words. They had jumped from a waterfall before, but now things were different. Things were so different now.

I looked at their dad, and then at my children, fear overloading my soul. My son had epilepsy, his future was unknown. But I couldn't waste this. I couldn't regret the rest of Luke's life, could I?

I couldn't.

So I nodded my yes, swallowed my heavy fear and did what I knew was the right thing to do.

I let Luke jump.