Women Fled To Nature During The Pandemic. It Might Have Made Their Mental Health Worse.

Content warning: This article contains discussion of suicide, depression, and other mental health challenges.

Going out to glam events multiple times a week used to be a big part of Amanda Moran’s life when she lived in Miami. But just before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the city in 2020, she escaped to Boulder, Colorado. Rather than move to another big city, she wanted to get closer to nature to explore its healing properties while enrolled in an herbalism program.

There, she traded skyscrapers for tall pines and mountains, and nights out for days on the trails. Instead of spending time in restaurants and clubs, Moran foraged wildflowers to turn into tinctures. At first, she loved it.

“I thought, This is the best place in the world,” says Moran, now 29, who co-founded the botanical-infused beverage company Beauty Booze after her move.

But after only one euphoric year in Boulder, the honeymoon phase began to wane. She felt alone. As a first-generation immigrant from Brazil, she missed her community of Portuguese-speaking friends in Miami, as well as the perks of the big city.

For Moran, being in a more nature-centric environment “definitely wasn’t life-changing in the way that I thought it was going to be long-term.”

Hundreds of thousands of people moved from urban areas to smaller cities and towns during the pandemic.

For many, moving was a way to escape the COVID-19 risks and restrictions of densely populated areas that were negatively impacting their mental health, according to Ariel Landrum, LMFT, a therapist at Guidance Teletherapy Family Counseling Inc.

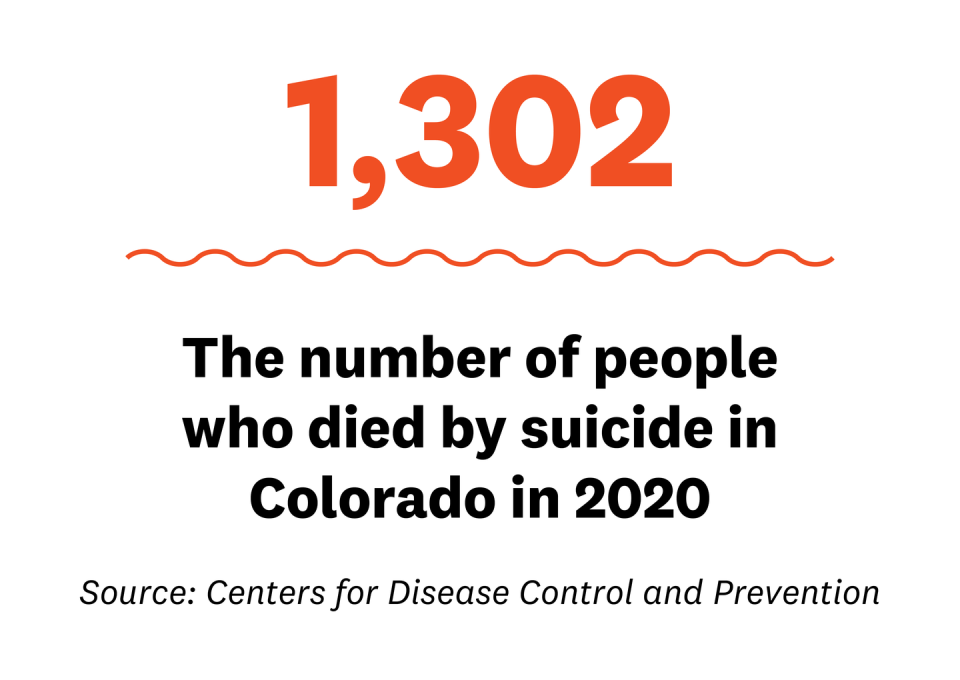

What they might not have realized is that folks living in more remote and rural parts of the country have long struggled with mental health issues. In fact, a cluster of states in the Mountain West that exploded in population during the height of the pandemic is known as “The Suicide Belt.”

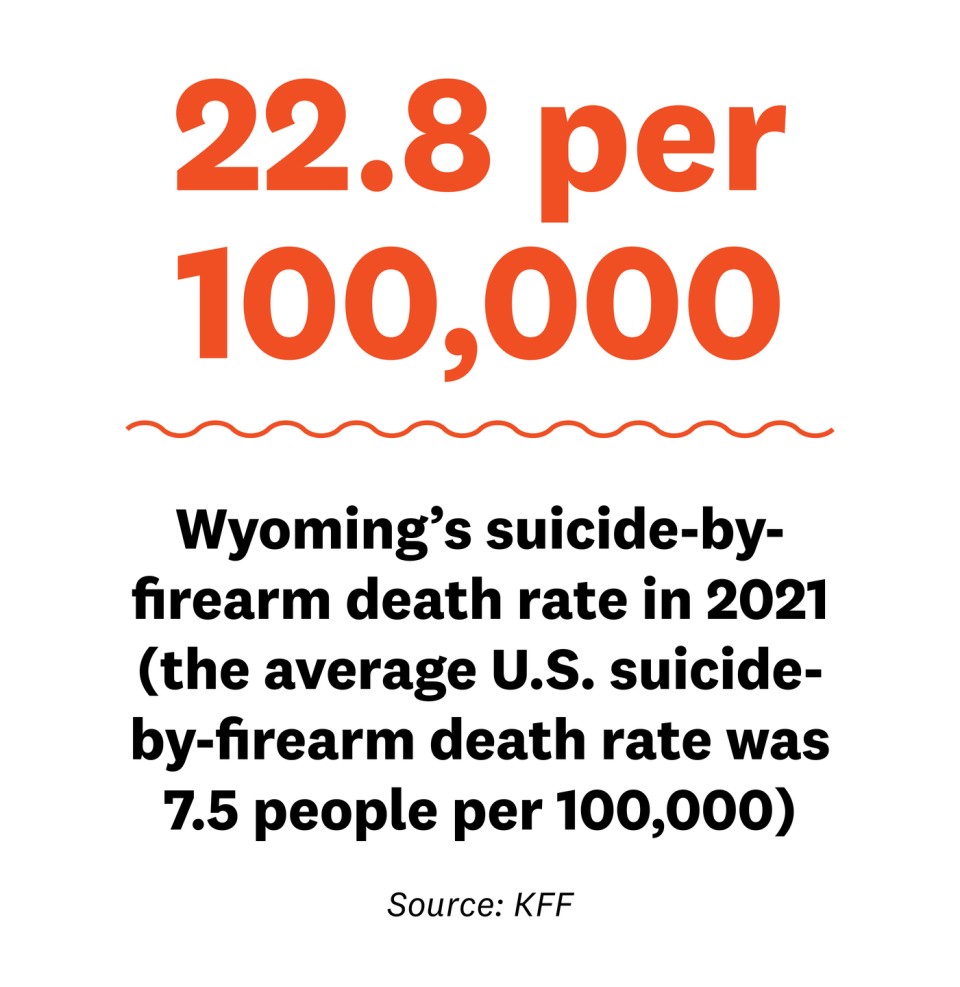

Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, Colorado, Idaho, and New Mexico consistently rank among the top 10 states with higher-than-average suicide rates. In 2020 in Wyoming, for example, the suicide rate hit 30 deaths per 100,000 people, and it surpassed 20 per 100,000 people in the other named states, per statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The difference is stark when compared with the national suicide rate of 14 deaths per 100,000 people.

These five states are also rated by Mental Health America as having a higher prevalence of all mental illnesses. Financial stressors, geographic isolation, easy access to firearms, lack of mental health resources, and the transient nature of resort communities are cited as some of the main contributors, per the University of Colorado’s School of Public Health.

And while there’s a country-wide mental health care shortage, with fewer therapists and psychiatrists working in the profession than ever before, the deficit is greater in rural and low-income areas, per data from the Rural Health Information Hub. “There’s more access to mental health care in the major hubs,” says Cassandra Fallon, LMFT, a therapist who works for Thriveworks in Colorado Springs.

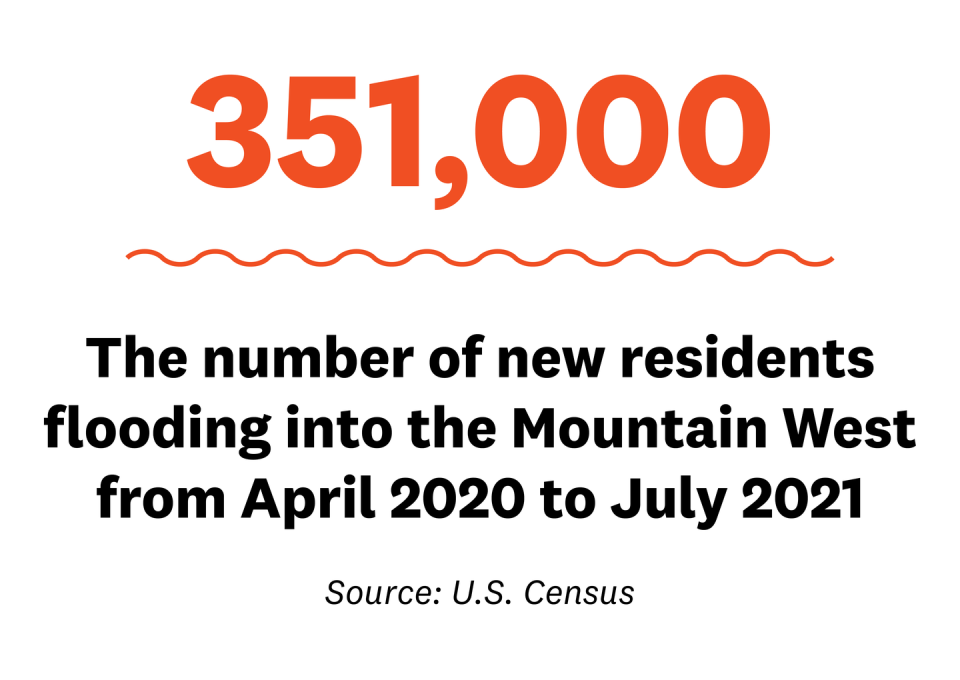

The care gap has only widened in some rural areas over the past three years as work went remote and people fled cities for wide-open spaces. Census data shows that the Mountain West in particular added 351,000 new residents between April 2020 and July 2021, with Idaho’s population increasing by 2.9 percent as the state became the second-fastest-growing, after Florida. This massive population influx has caused other detrimental impacts too: housing shortages, rising prices, and resource scarcity, to name a few.

Despite these issues, the country’s remote destinations are often touted as a boon for mental health.

Eager to develop her adventure-guiding skills, as well as find solace in the outdoors after being immersed in the frenetic energy of a larger community, Summer Vaughn relocated from a midsize college town outside Salt Lake City to a 650-person town outside Glacier National Park in Montana during the pandemic. The small town is quirky, the people are nice, and the views of the mountains are straight out of a painting, she says.

The sunny season was her high point. But Vaughn was hit with an unexpected sense of grief when the cold weather arrived. The seasonal workers she’d spent months building relationships with were suddenly gone, and she felt more alone than she ever had before. She hadn’t struggled with isolation in her college town. Despite her proximity to the park, a hike in the woods wasn’t enough to alleviate her anxiety and depression.

“Every health thing you’ll ever read says that going outside and getting into nature is going to solve your problems,” Vaughn, 22, says. “It does bring me a lot of happiness, but it isn’t a cure-all, and I think a lot of people think it is.”

The tendency to believe that moving to a picture-perfect destination will solve your problems, or make life significantly easier, is a concept recognized among mental health experts as the “Paradise Paradox.” The idea is that beautiful surroundings should neutralize mental anguish, but often, these postcard-worthy areas aren’t the solution and can even contribute to or worsen it in unobvious ways. Experts and folks who’ve lived in these areas for a while, like Alex Garcia, 30, recognize this common misconception among newcomers.

When Garcia was living in Summit County, Colorado, in the middle of the Rockies, rent was so expensive that she spent all her time working to stay afloat. She had a 9-to-5 marketing job and picked up a second gig at an ice cream shop. The extra hours on the clock left her physically and mentally drained, to the point where she couldn’t enjoy the gorgeous surroundings and learned firsthand the meaning of “Paradise Paradox.”

“I lived right on Main Street in Frisco, the most picturesque, beautiful spot,” says Garcia, who grew up in Denver and relocated to the mountains for a job in 2017. “When I moved there, I thought I would walk to get a coffee in the morning before work and sit outside while looking at the mountains.”

It was a dreamy idea. But in reality, she had very little free time. Work took over her life, and she found it difficult to step away at all since she was already struggling to make ends meet. “I rarely left my house because it was so hard to put down some of this work and prioritize myself,” she says.

Financial instability and lack of affordable housing can be extremely detrimental to mental health, says Dana Steidtmann, PhD, who works at the Helen and Arthur E. Johnson Depression Center at the University of Colorado-Anschutz Medical Campus. Nationwide, rent is soaring alongside home prices, thanks to inflation related to increased demand and building material supply-chain issues. The influx of new residents to an area only compounds the issue, and small mountain towns were hit hard during the pandemic. Rent increased 20 to 40 percent in Colorado mountain towns in 2020, according to The Mountain Migration Report, compared to a 12 percent increase nationwide.

It’s difficult to make friends when you have to work, say, multiple service jobs to pay rent, says Steidtmann. Plus, if you can’t afford to live where folks hang out, you’re forced to commute in from the outskirts of town. “Having that network is directly related to well-being,” she says. “And while it’s never easy to develop a social support network, there are things that make it that much harder in rural communities, particularly in mountain towns.”

The stress of trying to make ends meet, and do it alone, takes a toll. “Bodies are not designed to handle chronic stress, which is often a trigger for mental health conditions like depression and anxiety,” says Steidtmann.

The expenses of “living the dream” build up a lot of pressure too. And folks who live in vacation destinations frequently rely on substances to cope. Ski resort employees have a significantly higher risk for alcohol and drug abuse than the general population, per a 2017 Swedish study. And that’s true not only in Sweden. Fallon says vacationers and residents alike in American mountain towns and rural areas often turn to alcohol and drugs for relaxation as well as coping. “Substances give someone the ability to disconnect and ignore their circumstance for a little bit,” she says. Outdoor recreation and substance use have a storied past together on and off the trails and ski runs in small, nature-centric towns, which can of course contribute to declining mental health.

Simply being at higher altitudes may also be risky: Moving from low elevation to high elevation is strongly linked to depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, compared with remaining at low elevation, research shows. Less oxygen leads to a decrease in serotonin, a neurotransmitter that controls your mood and is responsible for happiness. That decrease not only makes you feel crummy but may also reduce the effectiveness of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), or antidepressant drugs.

People who aren’t yet acclimatized to living with less oxygen are the most prone to mood swings when exposed to elevations above 9,800 feet, whether or not they have depression or take SSRIs, according to a 1996 study, “The Effect of Altitude on Cognitive Performance and Mood States.” One line reads, “The initial mood experienced at altitude is euphoria, followed by depression.” The statement is all too familiar to many folks who’ve relocated to the mountains.

The West has been idealized as a place to get away from it all, which sets folks up for disappointment.

The “rugged individualist” mindset of the region doesn’t help either. Pulling yourself up by your bootstraps is an Americanized belief, one that’s only perpetuated by the survivalist nature of rural communities, says Landrum. Think of the kinds of people who are associated with living out West: extreme sport athletes, risk-takers, tough cowboys, strong and stoic ranchers, characters from the show Yellowstone.

To talk about struggles can be even more taboo in these places, and the dream-life exterior can perpetuate mental health issues because folks living there don’t want to seem ungrateful or admit their anguish. People can end up dismissing their own or others’ issues.

Research suggests that individuals living in rural areas are significantly less likely than residents of urban areas to seek professional help for psychological distress, according to a 2020 article, “A Call to Action to Address Rural Mental Health Disparities,” from the Journal of Clinical and Translational Science. It explains that these reasons “include stigma (both public and self-directed) and limited mental health literacy.”

Many of the people populating these towns are visitors on vacation during the busy season, and they’re more likely to appear happy and active, say Landrum and Fallon. But if you live in a vacation destination year-round, you’re not immune to the ups and downs of reality. “There are extremely wealthy people who are vacationing here, and then there are the people who are working, usually in hospitality, to live here,” says Fallon. “There’s no middle.” The income inequality, and the juxtaposition of the two communities, with one catering to the other, can lead people to feel insecure and unmotivated. “People have to make a lot of sacrifices to live here.”

Insular communities can be tough on transplants.

Before committing to moving to a new community, Alex Showerman, 34, spent fall 2021 to spring 2022 in an RV scoping out mountain towns where she’d feel welcome as a queer trans woman. It was important to her as a pro mountain biker and trail builder to move to a town in the West that had easy access to the outdoors, but equally important was her sense of safety.

“It was really cool to drop in and sort of live in these towns for a little while,” Showerman says. “I could see what it would be like to live there and picture myself there.”

Unlike other folks who settled into new homes permanently during the pandemic, Showerman could pack up and drive away when she started to feel unsafe or uncomfortable, as she did in Virgin, Utah. Although it’s one of the world’s best training grounds for freeriders, it’s a conservative town that’s not outwardly welcoming to trans people. Feeling she couldn’t freely be herself was impacting her riding, so she left to meet up with friends in Fruita, Colorado. “I knew if I went there, I would feel a lot safer around my people,” she says.

Lack of community was also a motivation for Mary Mathis, 27, to move away from Santa Fe, New Mexico. She relocated there from Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 2020 for a photo-editing job, but when she was laid off, she felt she had no reason to stay other than the outdoor activities and the fact that the intensifying pandemic made navigating another move even more difficult.

But the trade-off for proximity to nature was loneliness and separation from her loved ones. “Yeah, it’s a freakin’ paradox,” Mathis says. “At the end of the day, you’re texting your friends wishing that you were with them.... You do feel like you’re in paradise, but then you’re like, But I’m here alone.”

Small towns, particularly resort towns, are notorious for being tough on transplants. The resource scarcity can create a competitive atmosphere and lead long-time locals to (justifiably) fear destruction of the area’s natural outdoor assets and inflation of housing prices.

Still, when newcomers are able to integrate into a small community, there can be noticeable upsides. Megan Lewis, LCPC, LHMC, splits her therapy practice between Seattle and, more recently, Whitefish, Montana. Moving away from a city that is a beacon for mental health awareness and social activism to a small mountain town, Lewis was unsure how the community viewed mental health care. But she was excited by their hunger for services and has been met with appreciation for her line of work.

When the town or individuals who live there go through difficult times, there’s a special sense of group healing that she hasn’t experienced in cities. “You’re connected to someone who knows someone, so the conversations are really framed in compassion and empathy,” Lewis says. “When you grieve, you grieve together.”

Prospective transplants should understand the issues they might face before uprooting.

“I think one of the biggest challenges in rural communities, and in mountain towns in particular, is feeling isolated and not having a support network,” Steidtmann says. “If you throw the pandemic into that, it’s that much harder to generate that for yourself.”

And then there are the other environmental and societal factors, such as cultural, religious, and political differences, that can impact mental health. While states in the Mountain West are diversifying and various racial and ethnic minority groups are making up larger percentages of the population, these areas are still predominantly white, per a University of Nevada at Las Vegas study published in October 2020.

“The town may not have cultural food, religious temples, or even celebrate diverse holidays,” says Landrum. “Tension from prejudice and racism is also a contributing factor.”

After that first year in Boulder, Moran realized she couldn’t relate in certain ways to her new community as the only first-generation immigrant in her friend group. She noticed there were few other Latinas in Boulder compared with her recent homes in Boston and Florida. “I never felt this way in Miami,” she says.

And during Showerman’s travels, going into small towns to get groceries or pump gas was stressful. She was never sure if folks were accepting of trans people. As she’d drive into town from camping in the woods with her dog, her heart would start racing. She could feel herself becoming closed off to the idea of socializing while she was there. “I was super nervous that all it would take is just one person to decide that they were going to make a political statement and harass me,” she says. “I didn’t realize how much it was grating on me until months later, when I was living in a very safe, queer-friendly space. I look back and I’m like, wow, I was really scared.”

Now that she’s settled in Snoqualmie, Washington, a ski resort town less than 30 miles from Seattle, she feels immense relief. For her, it’s the just-right mix of nature and proximity to a bigger city plus the open-mindedness that often comes with it.

Experts say awareness of the Paradise Paradox and more resources to battle mental health crises are needed in rural western towns.

More and more efforts are being rolled out to address the current shortage of mental health professionals in rural areas. Loan-forgiveness programs from state and federal health departments incentivize mental health providers to move to rural areas or return to their hometown to practice after completing their training. Timelier programs are launching to help too.

For example, the Blue Cross of Idaho Foundation for Health in November 2021 gave $1.5 million to help Idaho State University serve rural communities. Colorado passed the Behavioral Health Recovery Act of 2021, setting aside $9 million in financial aid for rural and low-income students to obtain credentials in behavioral health programs. Montana has the Montana Rural Physician Incentive Program, and Alaska has a loan-repayment and direct financial incentive plan called the SHARP Program.

Grassroots organizations offering support and awareness of these areas’ issues have also sprouted up. The Tahoe Truckee Suicide Prevention Coalition launched in 2014 after a rash of deaths by suicide in Truckee, California, and Building Hope Summit improves access to care in Summit County, Colorado. The Redside Foundation is another resource Vaughn has turned to because it offers free mental health assistance to adventure guides in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming.

Popularized widely during the pandemic, tele-health has made it far easier to find help as well. People living in remote areas don’t have to make the long drive into town to receive tele-health care, and it’s ideal for those who prefer to be treated in the safety and privacy of their own home. A provider also isn’t likely to be the therapist for the whole town. But it’s an option only if you have insurance or money to pay out of pocket. Vaughn adds that she hasn’t looked for a therapist because she can’t afford one right now.

Mathis found a tele-therapist to help ease some of her mental health troubles in Santa Fe. “I was having terrible anxiety, terrible depression, and just feeling really, really bad,” she says. Coupling therapy with medication for anxiety and depression, plus spending time rock climbing and running in the high desert, “would make me feel free and happy and light,” Mathis says.

But tele-health can only go so far. If you need to be hospitalized, for example, you might get transported to the closest metro area hours away, says Fallon. Then how do you get home?

“Tele-health is great at giving a little more access,” she says. “But it’s by no means the most intense treatment service that we can provide, so there still needs to be more.”

Luckily, the societal conversation around mental health in rural regions is shifting.

Steidtmann says she has noticed a change from the “good vibes only” mentality that’s associated with outdoor culture to one that is more “all vibes welcome.”

“Data suggests that younger generations are a lot more willing and even eager to talk openly about mental health compared to older generations,” Steidtmann says. “But I think for a time, if that’s the ethos your social group is living by, you might not feel very comfortable disclosing that you’re struggling or seeking help.”

Outside of therapy and prescribed medication, simple self-care acts, such as taking walks, checking in with a mental health accountability buddy, meditating, moving your body, journaling, and sticking to a routine can be powerful tools for mental health, experts say.

Battling isolation means looking for opportunities for connections, says Landrum. She suggests visiting an Indigenous center when you’re integrating into a new community; it can help you better understand and honor the area’s history and land.

As for socializing, Landrum suggests restarting a hobby or taking a class in town, which could increase opportunities for friendship. Joining a local cause, like an Earth Day event or the thrift store volunteer team, can also help a newcomer organically spend time around other people in the community and open themselves up to connection.

Regular check-ins with family and friends, like through Zoom coffee chats or online games, can also help decrease loneliness and lead to future plans together. Also, old-school though it may be, introducing yourself to neighbors immediately is always a good idea, Landrum says. She suggests bringing over some cookies or finding another way to start a conversation. And, if it’s possible for you to adopt, a pet can be a great source of comfort.

Getting familiar with a new home and way of life takes time. When people visit or move to higher altitudes, they often have to adjust to breathing with less oxygen. Landrum uses this physical example to illustrate how you must also adjust mentally to living in a new place, especially one with a much lower population.

Ahead of her second winter in Montana, Vaughn felt better prepared mentally for the sudden slowdown. Not wanting to spiral again into a depressive or anxious state, she declared her second winter one of healing and rediscovery.

The season’s slower pace gave her the time to return to passions and hobbies outside of her guiding profession. She started writing again. She took up linocut printing and crocheting. And she got out of her apartment for community events like the silly Barstool Ski Races.

At least for now, she plans to stay in Montana, though she wishes there were resources that could have prepared her beforehand for the advantages and disadvantages of mountain-town living. “Working and living in a mountain community does have a lot of downsides once you get past that initial wonderment of it,” she says. “There are things you don’t know until you live here. But it can be super rewarding too.”

Moran echoes those feelings. “Boulder was the first place I fell in love with instantly, and it provided me with amazing experiences,” she says. But she has since moved out of Boulder proper and into a neighboring suburb and is planning to leave Colorado in the next few years. Her next ideal home will be somewhere she can blend her Brazilian roots and community with her newfound love of the outdoors.

Being immersed in “nature was everything I was hoping for and more, but the issue was that it wasn’t enough to feel like I was completely happy in Boulder,” Moran says. “The lack of connection was too big to be covered up by the beauty.”

If you or someone you know is struggling, please reach out to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or text TALK to 741741 at the Crisis Text Line.

You Might Also Like