Women: Go Ahead and Strike, but Know That Many of Your Sisters Can't

What is the work of being female? The question has gained new relevancy in the last month, as the rapid-fire nightmare reel of the Trump administration's first weeks has given credence and popularity to a left-wing notion that long seemed like a pipe dream: the general strike.

A rash of planned strikes has cropped up in the last month or so. An organization calling itself Strike4Democracy announced a plan for "a series of mass strikes" beginning as soon as February 17. In the Guardian, a collective of activists including Angela Davis called for "an international strike against male violence and in defense of reproductive rights." Meanwhile, the organizers of the massively successful Women's March on Washington tweeted an enigmatic call for "General Strike: A Day Without A Woman." As the initial chaos of overlapping events smooths out, the strike against male violence and the Women's March strike seem to have settled on the same day: International Women's Day, March 8.

It's happening. #ADayWithoutAWoman pic.twitter.com/V2gVzueeEh

- Winnie Wong (@WaywardWinifred) February 15, 2017

But what does it mean for women to go on strike in 2017? In an earlier era of highly segregated career paths, a "women's strike" had a specific, tangible effect: It made invisible work visible. No women meant no food on the table, no mysteriously emptied trashcans, no one to change diapers or type letters. No women meant no sex. (Yes, going Lysistrata is a real thing-and it occasionally works.) Forcing men to handle "women's work" was the only way to get those men to admit that it existed.

In an earlier era, no women meant no food on the table, no mysteriously emptied trashcans, no one to change diapers or type letters.

Today women have better access to education and high-paying jobs than ever. But because of these changes it's harder than ever to define women's precise relationship to "work," or to pinpoint a specific problem that female workers can address through striking. Sure, we can walk out of our jobs-but we won't all be walking out of the same jobs, for the same reasons, and some of us can walk out much more safely than others. Before women can strike effectively, we need to redefine what female labor consists of, and what our refusal to perform it will really mean.

General strikes-a refusal to work, shop, or otherwise participate in capitalist systems, undertaken by workers across industries-have always been something of a preoccupation in socialist and anarchist circles. As Friedrich Engels put it, "[One] fine morning all the workers in every industry in a country, or perhaps in every country, will cease work, and thereby compel the ruling class either to submit in about four weeks, or to launch an attack on the workers so that the latter will have the right to defend themselves, and may use the opportunity to overthrow the old society." Of course, the vision of a four-week global revolution always strained credibility, and Engels was writing to condemn such a strike as unnecessary. Still, Marxist thinkers like Rosa Luxemburg continued to embrace the idea that spontaneous mass strikes, like those that kick-started the Russian Revolution, would not only force the hand of the ruling class, but would also radicalize the working class.

All of which sounds suspiciously like dorm-room talk from the sort of hip, young Brooklyn fellow who un-ironically calls people "comrade"-or would, in any other year. This year, not only are people desperate enough to consider formerly unthinkable options, many of us recall the euphoric rush of being surrounded by thousands or millions of other activists at the Women's Marches in January. The simple, profound realization many marchers reported-Wow, there are a lot of us-is where general strikes begin. And the International Women's Day and Women's March strikes are exciting precisely because they harness revolutionary activity to this new surge of intersectional feminist resistance.

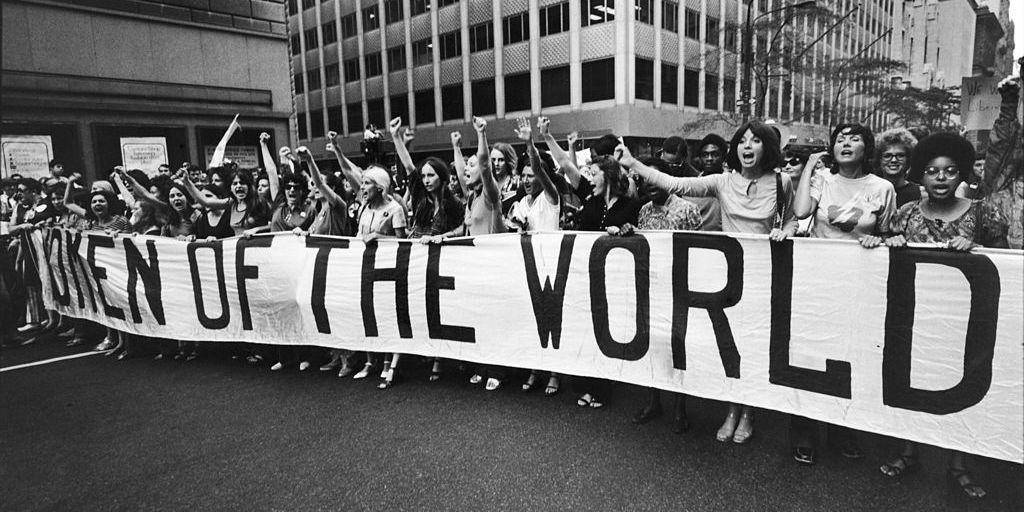

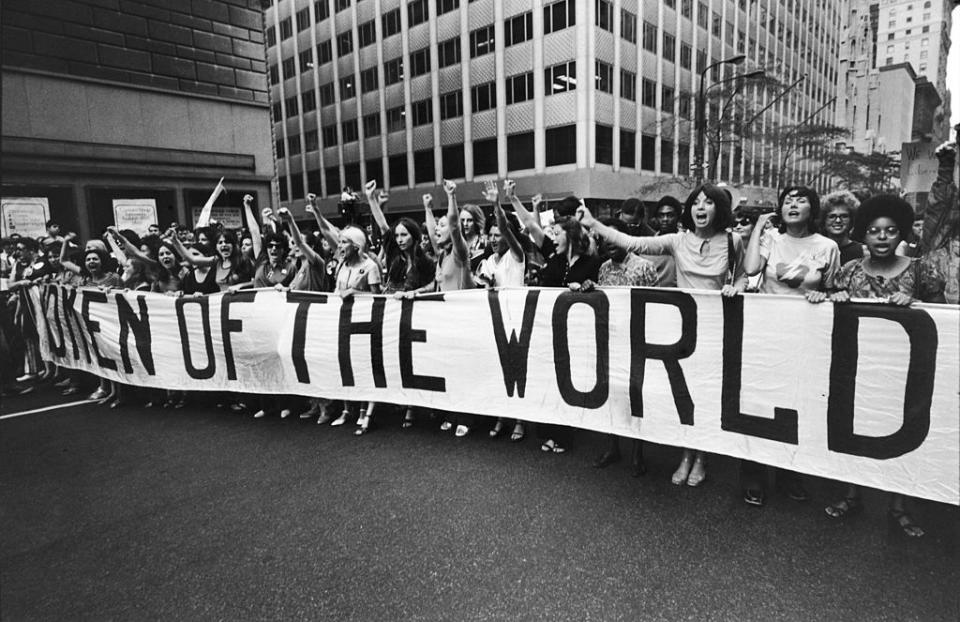

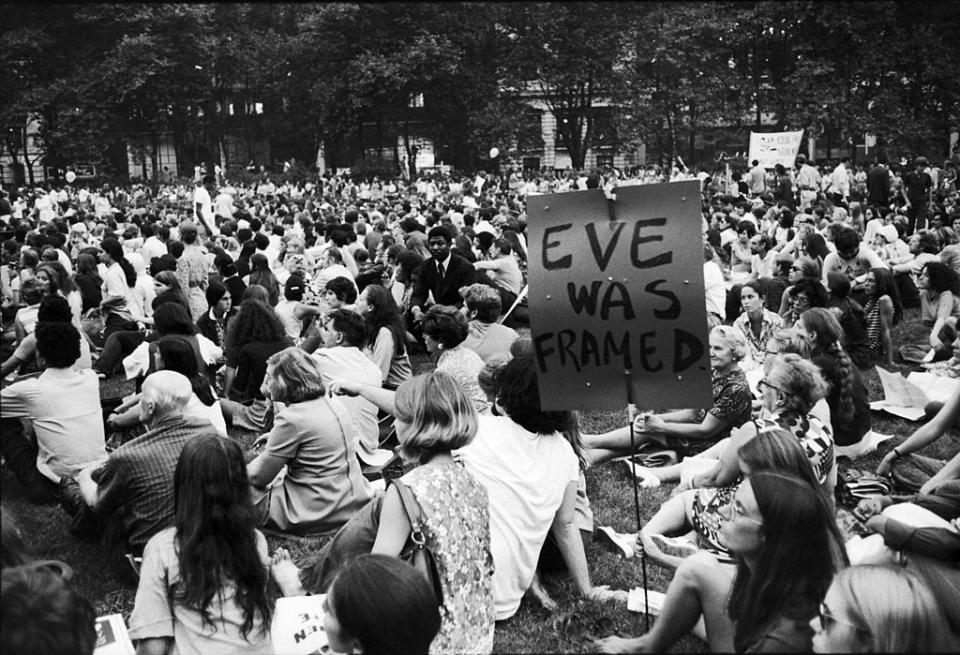

This, too, has a history. Before the Women's March, the largest feminist demonstration in U.S. history was the Women's Strike for Equality, staged in 1970 by the National Organization for Women. The strike's demands are still radical-and still, frustratingly, out of reach-in 2017: "Free abortion on demand, equal opportunity in employment and education, and the establishment of 24/7 childcare centers." Those child care centers were supposed to be free, too, by the way.

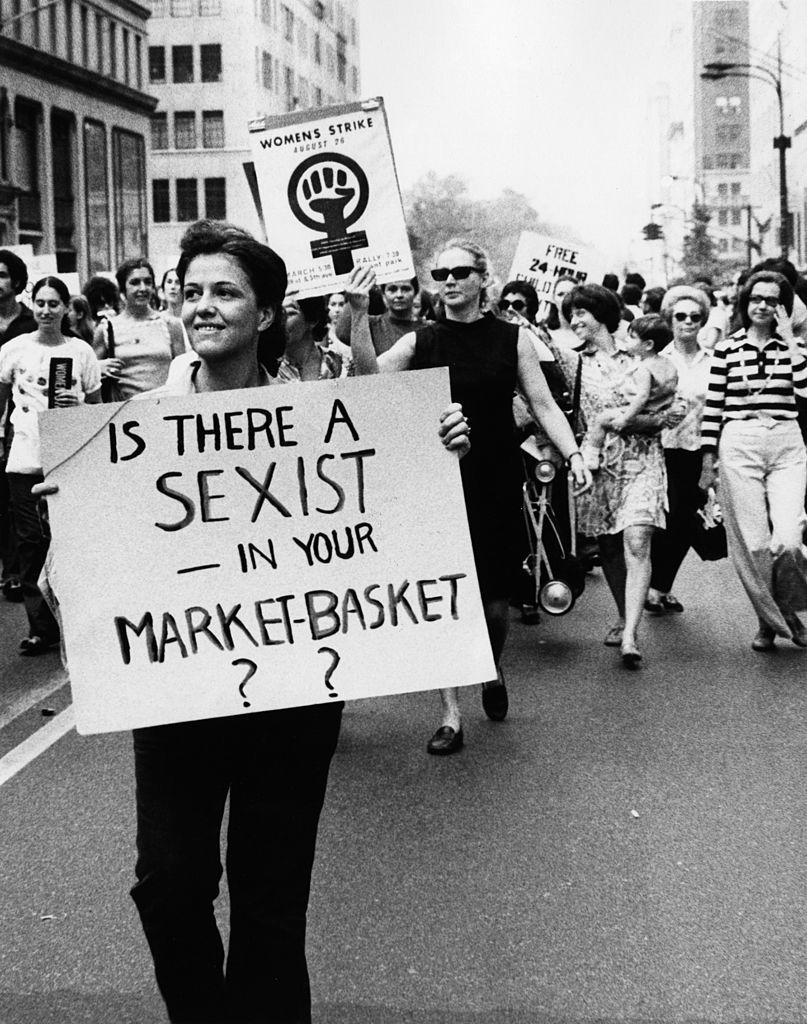

Younger feminists, accustomed to thinking of Friedan as the dull, uptight Margaret Dumont of second-wave feminism, would be shocked by her rhetoric in the call to strike: "I propose that the women who are doing menial chores in the offices as secretaries put the covers on their typewriters and close their notebooks, and the telephone operators unplug their switchboards, the waitresses stop waiting, cleaning women stop cleaning and everyone who is doing a job for which a man would be paid more stop," Friedan said. "And when it begins to get dark, instead of cooking dinner or making love, we will assemble and we will carry candles alight in every city to converge the visible power of women at city hall."

In 1970, this kind of thing was a joke. New York City police, expecting the strike demonstration to peter out quickly, allotted it one small lane on Fifth Avenue. It overflowed the street, the city, and the day of the strike itself. Ninety other cities participated. In one demonstration, women occupied the Statue of Liberty to protest "the hypocrisy that woman represents liberty"; reports from the time include snatches of chants and slogans that show, if nothing else, how very little the second wave worried about seeming "likable." (Sample: "There'll be men upon their knees to us and begging for their lives / And some we'll spare and some we'll not, for justice is our knife / There'll be judo, there'll be self-defense and rifles for each wife / For it's liberation time." Sung to the tune of "Battle Hymn of the Republic," natch.)

Protest signs like "Don't Cook Dinner-Starve a Rat Today" made sense because, at the time, "women's work" meant something specific.

Yet the Women's Strike was successful in part because, despite naming several different "female" jobs in its call to action, it protested a problem common to female workers across industry lines. Protest signs like "Don't Cook Dinner-Starve a Rat Today," or Friedan's specific calls to waitresses and cleaning women, made sense because, at the time, "women's work" meant something specific: undervalued, often unpaid domestic and care work, or low-ranking support jobs whose effects no one noticed. This reality also enabled the Marxist feminist Silvia Federici to call for wages for housework, and events like Long Friday, a legendary Icelandic women's strike that was so effective that schools and child care centers closed down and men, unable to hand off their children to their wives, were forced to take them into work. "We heard children playing in the background while the newsreaders read the news on the radio," one woman recalls. "It was a great thing to listen to, knowing that the men had to take care of everything."

Women's strikes have typically succeeded when they have some clear idea of what women's work is, some obvious problem that will become clear through women's strategic withdrawal-for example, a French strike in which women left work early (to symbolize the time of day they stopped getting paid, as compared to men with the same job). Without a specific, labor-related point, after all, a "strike" is just a particularly righteous personal day.

In 2017, there are still some fields that are predominantly "women's work." Nurses and elementary-school teachers are mostly female, for example. Domestic and child care work is still largely assigned to women, and still draws bad wages when it draws wages at all. The Guardian statement specifically calls for a "a feminism for the 99%," and calls upon women to "[abstain] from domestic, care and sex work"-yet, because those positions are still brutally undervalued, and frequently exploitative, striking is likely to be much riskier for those women than for women in the middle or upper classes. A woman with a comfortable office job may be able to "strike" simply by taking paid time off and feel confident that her job will be there when the strike is over. But for women in lower-wage positions with few or no protections, leaving for even a day might mean going without necessary wages, or incurring the wrath of an abusive boss, or even losing her job entirely. (Another useful note from history: The 1970 Women's Strike made sure to schedule its march for 5 P.M. because many women would not be able to get a day off.) True, part of the point of a strike is for middle- and upper-class women to stand in solidarity with working-class and poor ones, protecting them from reprisal by joining in the action-but it's still worth noting that protest itself can be a luxury.

The 1970 Women's Strike made sure to schedule its march for 5 P.M. because many women would not be able to get a day off.

As for those middle-class women: For the very reason that women have slowly been allowed access to higher-ranking jobs, the feminization of work is now far harder for them to identify or rebel against in specific terms. A "women's strike" now might mean that a company has to function without its human resources managers or PR department (both female-dominated jobs) but still have most of the sales and IT staff. Or it might mean that a female CEO has to do without her nanny and her secretary, putting her in the position of being the potentially vindictive boss. As feminism has progressed, women have more access to power-but that also means their relationship to power has become more complex, and that feminist sisterhood has more potential pitfalls and loopholes than ever.

Similarly, the feminist discussion of women's unpaid labor is still happening, but nowadays, it tends to focus on blurrier concepts like "emotional labor"-the diffuse, ongoing work of providing emotional support and maintenance, whether or not one feels like it. It's undeniably true that men aren't asked to perform emotional labor at the rate women are, and that it is draining. But if we (rightfully) include emotional labor on the list of "care work" that we're on strike from, then what does an emotional labor strike look like? It's easy to take off work and stop shopping, but do you also spend the whole day forgetting birthdays and refusing to smile?

These questions aren't meant to undermine the women's strikes, which are (again) exciting for their promise to unify feminist theory and revolutionary practice. To its credit, the Guardian statement lists many contemporary strikes the organizers aim to emulate, in places like Poland, Ireland, and South Korea. It's also worth noting that the Women's March itself was initially criticized for the fuzziness and non-specificity of its goals, and it still became the most successful protest in U.S. history. It may be that, just as all the old revolutionaries promised us, we will discover our power through the very act of striking; we'll see what "women's work" looks like when women stop doing it.

We are at a moment of unexpected possibility. If we're able to seriously discuss a general strike, then any number of previously unthinkable options are within reach. These movements are being formed out of resistance to unacceptable conditions, and yet it might also behoove us to get more creative, and more specific, when we envision the world we want. We may be able to ask for more than we think.

You Might Also Like