A Woman Hid This Secret Code in Her Silk Dress in 1888—and Codebreakers Just Solved It

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

A vintage dress purchased at an antique shop a decade ago contained a hidden code that has baffled people for a decade.

The code was broken by a data analyst at a Canadian university.

The 1880s dress was in tune with telegraph shorthand and meteorological information.

For a decade, codebreakers have tried—and failed—to solve the case of the crumpled paper that was found stuffed in a secret pocket under the bustle and inside the seams of a silk dress from the 1880s. Over the years, the mystery even earned its own moniker: The Silk Dress Cryptogram.

Now, we have some answers—and they come from unlikely sources: the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and a data analyst at the University of Manitoba.

The mystery starts in the 1880s, when someone wearing the dress tucked a coded message inside the secret pocket of what was considered a business-casual get-up. The paper was eventually forgotten, and the dress ultimately abandoned, until Sara Rivers Cofield purchased it to add to her collection in 2013 at an antique shop in Maine.

That’s when the fun starts. Rivers Cofield posted a blog at the time about discovering not only the completely concealed secret pocket, but also what appeared to be a code. “I’m putting it up here in case there’s some decoding prodigy out there looking for a project,” she wrote on her blog.

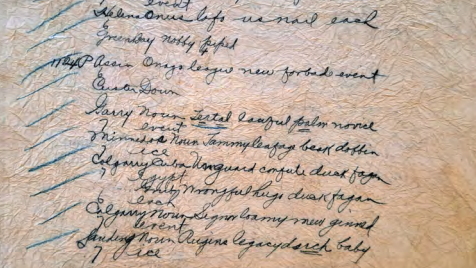

For a decade, the code remained, well, coded. Questions lingered over what, “Bismark omit leafage buck bank,” “Calgary Cuba unguard confute duck fagan,” and, “Spring wilderness lining one reading novice” possibly meant.

There were also numbers between the lines, each marked off with a different color and “time-like notes in the margin” of 10pm, 1113pm and 1124p. “I feel like those clues actually DO point to code of some kind,” Rivers Cofield wrote.

The theories proliferated. Illicit gambling codes? Dress measurements? Spy talk? Nope. After an initial flurry of unfounded guesses, the more experienced codebreakers focused in on the note being a type of telegraphic code, a shorthand created to limit the number of words sent as telegraph companies charged by the word.

Wayne Chan, a data analyst from the University of Manitoba and hobby codebreaker, took up the mantle. Working in the university’s Centre for Earth Observation Science, he was soon scouring through 170 telegraphic codebooks. Nothing.

The Silk Dress Cryptogram rose to become one of the top 50 unsolvable codes in the world, but Chan wasn’t done. He eventually stumbled upon the old “Telegraphic Tales and Telegraphic History” book and read about weather codes used by the U.S. Army Signal Corps, the group that served as the national weather service during the late 1800s. He drew a parallel between the dress and the examples in the book of code employed to send weather observations.

Chan had a thread to pull. He yanked. Soon, he was working with the NOAA’s Central Library in Maryland and finding unsearched weather telegraph code books, including one published in 1892 that proved he was on the right track. Combining resources, Chan cracked the code, publishing his findings in the journal Cryptologia.

As NOAA explains in a post, each line on the crumpled paper indicates weather observations at a given location, coupled with the time of day. That information was telegraphed into a central Signal Service office in Washington, D.C.

The format follows with the unencoded station location, followed by codewords for temperature/pressure, dew point, precipitation/wind direction, cloud observations, and wind velocity/sunset observations. So, “Bismark, omit, leafage, buck, bank” really means the weather in Bismarck, then in the Dakota Territory, had an air temperature of 56 degrees Fahrenheit with a barometric pressure of 30.08 inHG (omit), a dew point of 32 degrees (leafage) on a clear day with no precipitation and wind from the north (buck), all with a clear sunset and a wind velocity of 12 miles per hour (bank).

There you have it.

The code was tricky to break because only government officials creating weather maps used it. Adopted in 1887, the code allowed for six words to provide an entire report for a location.

Digging a little deeper, Chan tied the deciphered code to a specific day, believing the exact day in question was May 27, 1888.

Chan says that even with the code broken, there’s still plenty of questions about the owner. Rivers Cofield found the word “Bennett” written on a label indie the dress, but Chan couldn’t connect that name with a female member of the clerical staff working in the D.C. office of the U.S. Army Signal Service at that time. Of course, there’s no way to know if Bennett even relates to dress ownership in May 1888.

Solving one mystery leads to another. But at least this one doesn’t have a mind-bending code to crack.

You Might Also Like