I Wish I'd Told My Friends Just How Broke I Was

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

One summer day in 1991, a mother of three walked into McDonald's on her lunch break. She knew she could get a hamburger there for just 39 cents. The six credit cards in her wallet were useless, each one a lifeless plastic symbol of a maxed-out limit. She searched the depths of her purse for stray coins, and then she searched the cracks of her car, but she had done this so many times before that there was nothing left. She did not have 39 cents.

This mother was my mother.

She left McDonald's and went back to work hungry. Then she drove home, to our house, which was more like a luxurious jail in which we were serving a sentence of an unknown stretch, panicking toward bankruptcy.

My parents had bought this dream house—complete with a pool and a dock on the bayou—in July. My dad lost his job that October. Since then, my mom, a teacher, had cooked meals with less meat and more veggies, then fewer veggies and more pasta. She put gas in her car a dollar at a time. When the phone rang, she yelled, "Don't answer it!"

She had met friends in the neighborhood's women's club, but now she didn't have the $3 it cost to go to a meeting. She told them every reason but the real one for not attending. She found an excuse to be busy when they wanted to go out for dinner. Lies led to more isolation, as she and my father tried to hide this crisis even from us, and their friends drifted away in the face of what seemed like rejection. She didn't know anyone else this was happening to, and so she kept it to herself, the shame of it enclosing her as depression.

We kids were soon initiated into the covert operation of being broke. Once cars started disappearing, once the cable turned to fuzz and the lights went out during dinner, even before we moved into what I called The Stinky House, we knew our family was In Trouble. I was never told not to tell anyone, but I feared people would find out. Every detail felt like a shameful event: the times my mom's credit card got declined, the way the laundry piled up in the house because laundry could wait when just living was exhausting. All this added up to a secret life contained in the walls of my home, an aspect of who I was that threatened to reveal itself when I moved about the world. It wouldn't be until high school, with all three of us kids working, that the roller coaster would plane out.

I had lived through all this chaos, and I should have planned to do better for myself. Instead, I took vacations I couldn't afford. I ate at restaurants when I could have learned to cook. If Mint.com could label my transactions truthfully in a pie chart, the labels would be: Laziness, Entitlement, and Ego. I spent a lot of money pretending I could join parties I couldn't afford to join. I was trying to buy my way out of the shame of being broke, which only deepened my debt and made me wonder again what was wrong with me.

Over and over I paid insufficient funds charges, filled my gas tank with the $20 just freed on my credit card by paying the minimum the day before, and lay awake with my heartbeat and my head tumbling, trying to find a way through the next month. I'd wonder how my mom did it with three kids, try to imagine that kind of pressure. I knew better. I just couldn't seem to do better. It was not that I was young and stupid. If there was one thing I was educated in, it was the importance of setting yourself up for the unexpected.

I repeated this pattern until I found myself living back home at 28 with my mom, who was financially stable by then. I borrowed her car and borrowed her money. It was not rock bottom, but it was as close as I'd ever like to come. I was so sick of that desperate clench in my chest, that panic. Finally, I decided to try one last tactic: shameless transparency.

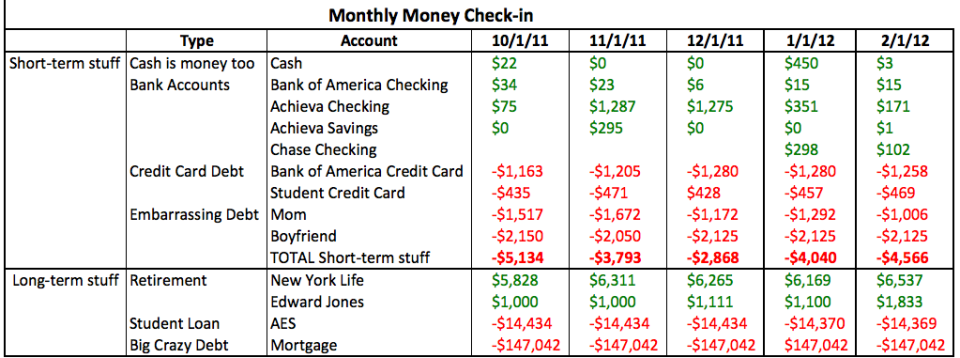

First I had a hard conversation with Excel, because my debt and my crisis had been a cloud I walked around in, and I needed clarity. I didn't have a total of what I owed, so I couldn't have a plan.

Then I enlisted my friends. I told them I was blogging to get out of debt, and sent them the link. I posted a screengrab of my spreadsheet there with all my account balances.

The only person who ended up religiously reading my monthly check-ins and nerdy charts was Jeri, my best friend's mom. But over the years, not wanting to disappoint her, that tiny accountability of her comments, was enough.

Next I started 'fessing up about money in real life, even when I really didn't want to. I was surprised when people nodded their heads, saying, "Been there," or even, "Me too." When my hairdresser, who had been a student, graduated to a fancy salon, I told her congratulations—but also that I couldn't afford her anymore. She put me on the friends and family list and charged me half price. When my new boyfriend and I drove three hours to a music festival only to find out it would not be the $40 we thought, which was already a stretch, but instead $140, I admitted that I just couldn't do it, even though I had that much in my account. We watched people skipping and cheering toward the entrance, and then we got in the car and drove three hours back home.

"Shame needs three things to grow exponentially in our lives: secrecy, silence, and judgment," says scholar and speaker Brené Brown, one of the first researchers to study shame deeply. "Shame cannot survive being spoken. It cannot survive empathy.… Shame depends on me buying into the belief that I'm alone."

Brown defines shame as "the intensely painful feeling that we are unworthy of love and belonging." The catch is that if you feel too shameful about your financial crisis to tell people, you'll never know just how not alone you are. If you have financial problems, let me tell you that you do belong, as the statistics show. In a recent article for The Atlantic, "The Secret Shame of Middle-Class Americans," Neal Gabler reports that 55 percent of households couldn't cover a month of lost income if they had to, and nearly half of all American adults are "financially fragile." He admits that, like most Americans, he could not scrounge together $400 in an emergency. Americans who are in debt are in this together, but when it's only our names we see on the bills, we feel like we're in it alone.

We label financial disaster as a personal failure, discounting the $187 billion spent in this country annually by advertisers to essentially hack our brains and configure them to release our money. As with the obesity epidemic, we blame debt on personal shortcomings without factoring in the forces that have made an industry out of leveraging our most primal cravings against us.

"People think that their decisions and choices are most of the time rational and made consciously, relating to their wishes, interests, and motivations," says Mark Andrews, a creative director, psychologist, and author of Hidden Persuasion, a book about how advertising uses psychology to influence our choices. "[The] fact is that most of our decisions in daily life are made on an unconscious level, which means we are quite vulnerable to persuasion attempts which affect our unconsciousness."

Yes, I messed up, but not in a vacuum. I got lost in a system that is complex and designed to be difficult to navigate, barely armed in a war that I didn't even realize was going on until I started to lose.

Finally, I started to read the fine print closely, and I started to take control of my finances. I started listening when my mom said to me, "Look at how these interest rates jump if you miss a payment." She got better, and so did I. My mom always said, "Your father and I balanced each other out in every way, except we were both bad with money." After I opened up about my mistakes, I was better able to see that my financial issues were the sum of my history, habits, and environment. They were not me.

I found the first step to living a financially secure life is the bravery to admit when you are insecure. Financial crisis is already like walking a tightrope. Secrets only make the rope thinner.

Gabler presented his debt as a social death knell, but statistics say that if you can't face a $400 emergency, neither can half your friends. And if you've all been shopping, dressing, and Instagramming your brunches to impress each other, chances are you could instead support each other and keep each other accountable. Coming out of the debt closet tapped into my friends' resources, ideas, and support. It bonded us. Over time, telling people just how broke I was got me out of the swirling cyclone of debt and fees and humiliation.

I still can't take a vacation or make a large purchase without wondering if I'm tipping myself into my next huge mistake, if I'll be desperate to have that money one day. But if I do find myself without an emergency fund, in debt, barely making it paycheck to paycheck, my friends will hear about it. I will go into Lock Down, a temporary state in which I trade my cocktails for a beer at home, the concerts for the park, and restaurants for my stove. My friend's mom Jeri will read my blog about it, I'll make a plan, and we'll all get through it together.

Paulette Perhach is a writer living in Seattle and the creator of The Writer's Welcome Kit, an online course that helps new writers figure out how to start. Follow her on Twitter and Facebook.

You Might Also Like