Wild Wild Country directors the Way Brothers: 'To tell the full story of Rajneeshpuram would probably take about 20 hours'

Netflix has the power to make Hollywood household names out of small-time filmmakers and actors. The Duffer Brothers were working on shorts and small projects before Stranger Things spawned an international fanbase in 2016. Nobody cared when Claire Foy was cast as Queen Elizabeth II, but fast-forward two years and her Crown pay inequality is global news. One suspects that for Maclain and Chapman Way, who currently don't even have a Wikipedia page, Wild Wild Country is about to change their fortunes, too.

The six-part Netflix documentary is only the third project for the directors (known together as The Way Brothers) but it has gripped viewers the world over thanks to its retelling of the unbelievable forgotten story of Rajneeshpuram, a utopian city built by a cult in a rural part of Oregon in the Eighties.

After directing their 2014 debut The Battered Bastards of Baseball, the brothers were introduced to a cache of 300 hours of archived local news footage of the Rajneeshees, as the cult's 7,500 members were known, and the commune in which they lived, and realised that the three-year-long saga of their occupation of the ranch was narrative gold-dust.

Sex, salmonella, arms and a turf war of multi-million dollar proportions were the building blocks of Wild Wild Country, but the Way Brothers' deft directorial touch has created a beautiful documentary that constantly challenges the viewer. Here's what they had to say about it:

One thing that really kept me watching was the moral ambiguity threaded through Wild Wild Country – as a viewer, you never know quite which side to agree with.

Chapman: I think with the current political climate we have such a kneejerk reaction to immediately decipher who is right and who is wrong. We were really excited about this story because the crimes that occured are documented and well-known but we were interested in pulling back the political layers and the cultural layers and diving into what led this group to commit these crimes. When you go on this journey it’s not a black and white journey, it’s becomes much more of a grey area, and hopefully forces the audience to do some critical thinking to figure out where they stand on these issues.

Can you sum up your feelings towards Sheela as a person?

Chapman: Sheela was one of the few interviews that we did that didn’t want the interview questions ahead of time, she said we could ask her whatever we wanted and she would answer us honestly. So we’re incredibly appreciative of being given that opportunity to talk with her. That said, Sheela has a very clear conviction of her ideologies and her beliefs and what she believes is right and wrong and what she was standing up and fighting for, and that’s what makes the series so interesting.

Depending on who you are and your life’s experience and where you’re from you can interpret this story in an entirely different way from someone else. And for those that know Sheela and are close to her understand that she is doing the best that she could do to protect her community and to protect her master and her family. I think it’s a really complex situation.

Maclain: We were interested in speaking to Sheela because she’s in a unique position where she’s not very well-liked or welcomed in Oregon – I think she would completely agree with that – but she’s been completely excommunicated from the Sannyasin community. She’s kind of like this one-woman island a little bit in the story. She’s telling you her side of events, she doesn’t have many friends or allies backing her up doing it.

So for us, when we were first looking to tell the story of Rajneeshpuram, she was very much on the top of the list of anyone we wanted to speak with, not just because she was such a key decision maker in Rajneeshpuram, but because it didn’t feel like anyone would come to her defence in the telling of the story.

Have you had any criticism that Sheela was presented as the criminal while Bhagwan was allowed to largely remain silent?

Chapman: Just from the women close to us who were involved in the project, they said it was really rewarding to see a complex feminist female character. A lot of times in pop culture it’s usually like a Wonder Woman character or someone who’s very easily identified as the hero in the story. And I think that the women we talk to and are a part of our project were really excited by all the different layers and complexities to Sheela.

Maclain: Sheela’s certainly someone that’s polarising regardless of whether you’re a man or a woman. We have people who totally see her as a freedom fighter and someone who was willing to create her own dynasty and future even if it was for another man. Sheela is certainly a feminist but she found her feminism through a guru – she was going to build a city, not just for him, but for this movement that she really believed in. I think that she was not just a mother to the community but a fighter, too, and a defender.

Bhagwan is so omnipresent but we know so little about him. How did you come to feel about him while making the documentary?

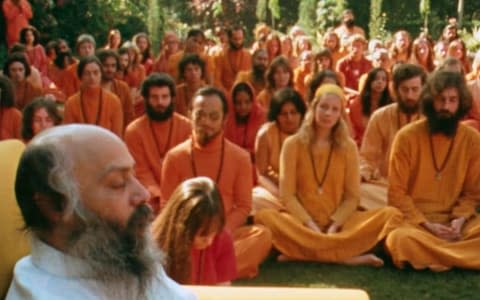

Chapman: We obviously did a lot of research into his life and his teachings and it’s very clear that those who buy his books and practice his teachings view him as a spiritual genius. He has a PhD in philosophy, he wrote over 300 books and for those who are seekers and part of the New Age world do see him as an enlightened man who was here to raise the consciousness of humanity. Everyone has a different perspective on him, my personal takeaway was that he was a mirror, he reflects what you project on to him, and if you see evil or if you see a conman that’s your projection onto him, or if you see someone loving and accepting of you, that’s also something that people put on to him. I saw him as a clear mirror.

Maclain:He’s hard to totally define. He spoke on so many different topics and was often incredibly contradictory of himself and even Sannyasin will tell you that. I think we were less interested in trying to do the Bhagwan biopic or a total analysis of the theology of Rajneeshees and we more became more attracted to the political and socio-divide story of Rajneeshpuram. But someone like Bhagwan, on a basic level, he built something – it was a movement, it was a spiritual movement and a religious movement that dated from the early Seventies, until today, even through his death in 1990 and beyond. There’s not too many people who were of the 20th century who did that.

I also think there’s a legitimate claim by oregonians who felt like their lives were very negatively impacted by the Rajneeshees, by Bhagwan and Sheela’s arrival in their space. They’ll tell you that earnestly, and I believe that they felt that way. That these years from 1981 to 1985 were just as traumatic for them as it was for the people who built the city, if not more. There’s obviously no love lost there, and I think that’s understandable.

One thing that elevates Wild Wild Country from other documentaries is the cinematography of it; it feels more artistic in scope than something like, say, Making a Murderer. How did you achieve this?

Chapman: We knew from the beginning that we weren’t out to make a traditional true crime story. Which is a whodunnit, who’s innocent, who’s guilty, what’s the evidence, we enjoy those stories but we didn’t have an interest in doing that for Wild Wild Country.

Maclaine: We worked with an incredible director of photography, Adam Stone, who is better known for shooting all of Jeff Nichols’ films, like Midnight Special and Take Shelter. We always joke that he was highly overqualified to work on our documentary series but we were lucky enough to work with him anyway.

But I think the conversation with Adam was to make this as immersive as possible. We kind of just wanted to drop the audience in from point one and keep you in that story for as long as possible.

Chapman: I think a lot of documentaries are information-based, it’s trying to add as much information as quickly as possible, but as filmmakers we’re really drawn to atmosphere and mood and tone and sound and how that also influences the story. We wanted to get these elements of the wild country out there and the elements because the landscape is so rugged and unique and you are out in the wild, we wanted you to feel those elements not just be told about them.

How did you sift through the hours of footage, and sort the wheat from the chaff?

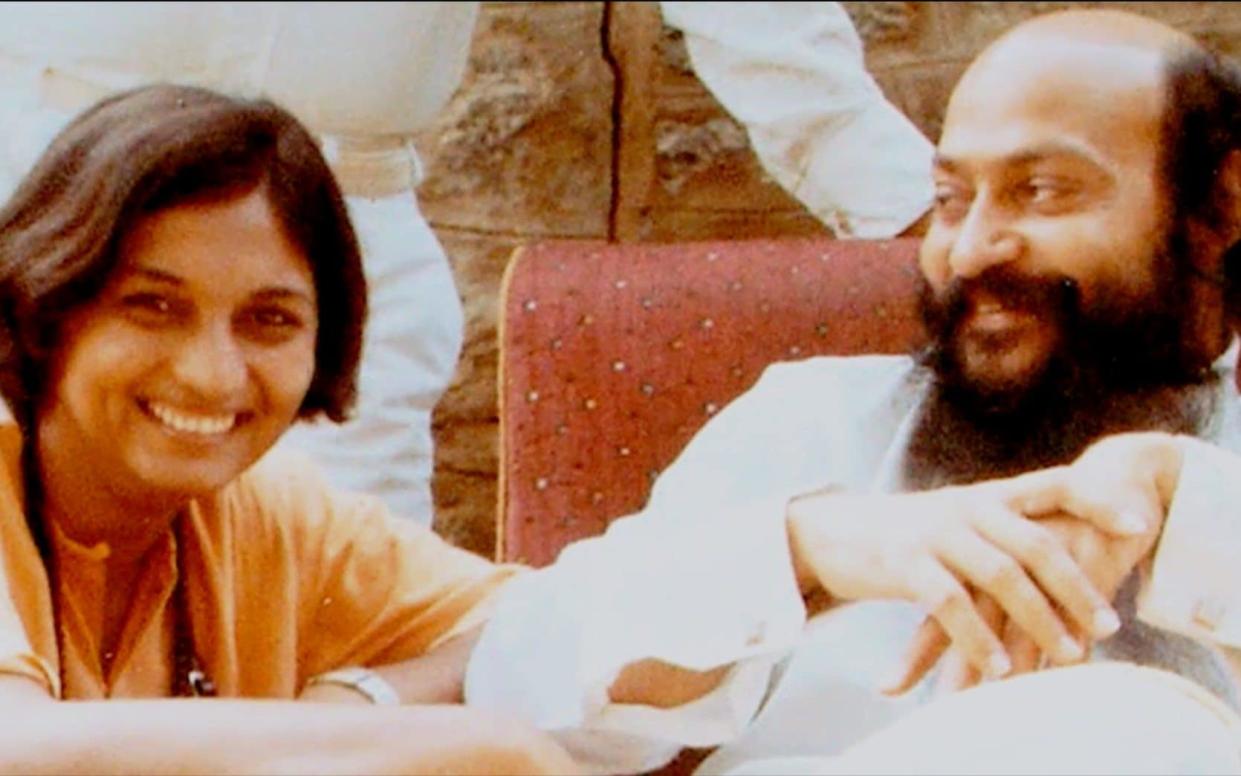

Chapman: While digitizing the footage, the first character who really jumped out at us was this Ma Anand Sheela. The more footage of her the more we saw her speaking more and we just came across this really feisty, provocative foul-mouthed woman who didn’t take crap from anyone and we were immediately drawn to her and we just felt like if we wanted to tell this in a long-form series, how incredible it would be to hear from her perspective and her lens. So we went through the archive and we narrowed down the list of characters and who we really wanted to speak with on both sides.

Was there anyone you wanted to speak with and weren’t able to?

Maclain: The first mayor of Rajneeshpuram, Swami Krishna Deva – they called him KD – his American name was David Knapp, and he worked directly under Sheela and was involved in a lot of the criminal doings that went on. He was the character that turned in evidence and gave a bunch of insider information on the group to the Feds. We contacted him a couple times and got him on the phone but he just made it very clear that this was something he was never going to speak about or talk about that he’d moved on from it and he had zero interest in talking about it.

Were you tempted to put the more scurrilous stuff in?

Chapman: We’ve obviously done a lot of research. A lot of that information came from Wayne McCormack who was a local journalist in Eastern Oregon at the time and covered a lot of this. And most of it had to do with the pre-beginnings of the group, when they were in India in the late Sixties and Seventies and there were instances of drug smuggling. We didn’t think it was something that was indicative of the entire movement or the entire group and we didn’t have anyone talking about it on camera, to be honest.

Maclain:We had a few interview requests for Wayne but he’s a busy guy. I think at some point talking about the criminality of the Rajneeshees we get into conspiracies to assassinate political appointees, there’s an attempted murder of Bhagwan’s murder on the ranch, we talk about the wire-tapping, Sunny herself talks about the time she got poisoned, we talk about the salmonella attack were 750 people get poisoned, so a little of it felt like the drug smuggling was small potatoes in comparison to people’s lives being on a hit-list. We tried to do as good of a job about the stuff that mattered without boring our audience.

The 30 best documentaries on Netflix

We were telling a story of Rajneeshpuram, and to tell the entire story of Rajneeshpuram would probably take like 20 hours. But we’re really excited, people have been coming out with new information and people have been coming forward with new information, and we’re really hoping that people continue to move the story forward and uncover more and more.

How did we not know this happened before?

I think there’s a few components. The first one was that no-one died. No matter how horrific the story ended up turning out to be, there were no deaths. And I think in America we’re much more familiar with Jonestown, we’re much more familiar with Waco, there’s just this huge death toll that occurred.

The second reason is that we went through a lot of the archive footage, it was really just reported on as this bizarre quirky story - there was just this Rolls Royce guru who had this compound. No-one was really diving into the issues the way that Wild Wild Country did. And I think when it ended it was just dismissed as this story that happened.

The third component was that the guru changed his name from Bhagwan to Osho and the organisation did this incredible job of rebranding him and the movement and kind of changed a lot of their biographies and the background of the movement and the Young Life community doesn’t like really talking about this story or about the past history of the ranch. I think it’s a combination of all those that it remained forgotten for so long.

Wild Wild Country is on Netflix now