My Wild Weekend at the Philip Roth Festival

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

You can’t get a good bagel in Philip Roth’s hometown. At least not in the radius of The Robert Treat Hotel, Newark, where I am staying. I try two days in a row. Google Maps directs me to a bagel shop in Harrison, New Jersey, thirty minutes away. Someone posting on the Reddit thread r/Newark says, “Take a train for an hour.” I end up at Whole Foods, contemplating the bakery case with growing despair. Finally, I give up.

I am in town for Philip Roth Unbound, a three-day festival put on by the New Jersey Performing Arts Center (NJPAC) on the occasion of what would have been Roth’s 90th birthday. Roth, one of the last titans of a certain type of mid-century literature, died in 2018 at age 85. The weekend promises panels and performances, a bus tour, a library tour, a marathon reading, and a play, featuring participation by literary stars and actors and friends of the late author. The roster impresses: Eric Bogosian, Tony Shalhoub, Sam Waterston, Ayad Akhtar, Susan Choi, Ottessa Moshfegh, Gary Shteyngart, Matthew Broderick, Peter Riegert, Lisa Halliday, Morgan Spector, John Turturro, and many more.

I am a Roth fan, a Jewish writer whose Jewishness is complicated by a non-Jewish last name and a childhood in South Carolina. A modern crypto-Jew, I was asked constantly growing up, as a way of getting me to declare myself, “Where do you go to church?” Roth’s writing about Judaism connects. The feeling of not being exactly the right type of Jew. But mostly, I admire his use of language, his sense of humor, his fearlessness.

Going in, I expect to meet others who connect, and whose ardor exceeds my own. Why else slog to Newark in March? I am curious about Roth, but mostly I am curious about the people who like Roth enough to sit through multiple panel discussions about his work. Who they are and what does Roth mean to them? What is his legacy in our fractured culture that doesn't value or even allow for the persona of The Great Writer anymore?

I arrive in Newark on a Friday afternoon in late March. It is the last weekend of winter, still chilly, still grey. The wind rips down the wide streets around Military Park, where the venue is located. Walking to the first event at the Newark Library, there is no one around. I wonder what happened here, then answer my own question: the late twentieth century.

The opening event is “Philip Roth: Reading Myself and Others,” with author Claudia Roth Pierpont (no relation to Roth, though she did write the 2013 biography Roth Unbound that gave the festival its name) and historians Sean Wilentz and Steven Zipperstein. They talk about Roth as a reader, and how his literary diet impacted his work.

I hear the words Auschwitz, Anne Frank, blowjob, Kafka, genius, baseball, Primo Levi, Joseph Conrad, Joshua Cohen. I hear the word masturbation, the phrase “the human comedy,” the phrase (Roth’s) “the insatiable realistic novel.” I am assured that J.D. Salinger was writing about the Jews. I hear an older lady with a skunk-like hairdo shouting toward the dais, “CAN’T HEAR YOU” approximately ten times. I hear a septuagenarian say the word “threesome” into a microphone.

Roth’s aim was to be as good as Joyce or Melville, someone says. He protected his time, his sleep. He hated the film adaptations of his books, but was pleased when the checks cleared. He “listened with his whole face.” He wrote at a standing desk. He was injured for life heaving a bag of potatoes in the army. He read in the evenings. He cared about awards.

In the Q&A portion, an audience member asks a good question: why did Roth hate Bob Dylan? The moderator says, half-joking, “Because Dylan won the Nobel.”

If you’re a writer, Philip Roth can make you feel like a slouch. He published 32 books. He won the National Book Award (twice), the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and on and on. So if you, like me, published one novel almost five years ago and haven’t sold a second yet, slowed down by a baby and a second baby, slowed down by having a job, you might feel that what you lack is ambition. You might find yourself thinking: maybe I should try to be like Joyce or Melville.

At a reception afterward, I throw two small plastic cups of white wine into an empty stomach. I am worried that no one is going to talk to me. I have planned an uninspired opening gambit: “What is your favorite Philip Roth book?” But it turns out this is unnecessary. The crowd, overwhelmingly elderly and Jewish, is dying to talk. Almost instantly, I receive an open-ended invitation to shabbat dinner in Brooklyn.

Everyone’s got a Roth anecdote. Here’s one a guy named Howard told me: Howard came across an inaccuracy in the novel The Plot Against America. Roth had misidentified a real-life conservative synagogue in Newark as reform. Howard saw Roth at an event, and told him. Roth replied, “Don’t tell the Jews.”

For the next event, we trek several blocks to the performing arts center. In the lobby: maelstrom. The crowd is here to see Mathew Broderick and Peter Riegert read Roth pieces. Two different people point out former New Jersey governor Jon Corzine, and several tell me to visit the statue of Abraham Lincoln by John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum, the sculptor behind Mt. Rushmore, in front of the Essex County Veterans Courthouse. Lincoln is seated, they all say (in fact it’s called “Seated Lincoln”), and it has a different feel from the Lincoln Memorial.

A small bookstore is set up outside the auditorium selling Roth titles and titles about Roth. Notably absent is the biography by Blake Bailey, which was published by Norton in the spring of 2021 and taken out of print almost immediately when multiple sexual assault allegations broke against Bailey. This controversy has stuck to Roth, maybe because of its relative nearness to his death, or maybe because much was made about how he hand-picked Bailey for the job.

Roth has long been called a misogynist, due to both the way he writes women and his personal life. His ex-wife Claire Bloom detailed the specifics of his alleged cruelty in her 1996 memoir, Leaving the Doll’s House. Roth had hoped, in selecting Bailey, who has written biographies of other complicated literary men like John Cheever, that he would be portrayed sympathetically, and that the work wouldn’t focus on the more sordid details of his life.

But if you were unaware of the subtle omission of the biography, the weekend would not tell you much about the unsavory elements of Roth’s reputation. Except for some throwaway remarks from a few panelists, about how the misogyny in the work is embarrassing for Roth and reveals his frailty, it doesn't come up at all.

We file in and take our seats. The actors’ performances are good, but language has already stopped registering normally for me. I feel tumbled by it like a rock in the ocean. I am unmoored by the sincerity of this event, and by the fact that its attendees are mostly older Jews. I think about the declining relevance of literature in America and the blighted small cities of the Northeast. I think about the loss of the way of life many of these people grew up with.

Meanwhile, Peter Reigert reads a passage from Sabbath’s Theater, one of the smuttiest books ever written.

By day two of Philip Roth Unbound, I am becoming unbound. After failing to locate a bagel, I attend a panel discussion called “Letting the Repellent In: Philip Roth and the Art of Outrage.” The panelists are entertaining (Gary Shteyngart), insightful (Ayad Akhtar), smart (Susan Choi), and provocative (Ottessa Moshfegh). Shteyngart tells a Roth anecdote: when he was just starting out, he was at an event at Russian Samovar in Manhattan. He walked past the bar with a woman, and there was Roth, drinking vodka. Shteyngart asked him for advice and Roth said, “Don’t eat butter. You’ll never get it up at my age if you eat butter.”

At this panel, I hear the words impulses, darkness, control, suicidal, botched circumcision, John Updike, Dwight Garner, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, Vivian Gornick (“who despises Roth brilliantly”), Franzen, Gaddis, The Twenty-Seventh City, The Corrections. I hear the sentence (Conrad’s), “The way is to the destructive element submit yourself.”

I attempt to submit myself to the destructive element. When we have a break, I go visit the house my mother grew up in, just outside of Newark. She lived with her mother and grandparents in working class Irvington, one town over. This was the late fifties, early sixties.

My grandfather was estranged from my grandmother and lived in a boarding house in Newark proper. He was a salesman who sold, among other items, pictures of Jesus door-to-door to poor Black people. My mother tells me there were different tiers of Jesus pictures, and the most expensive had a built-in light. When you plugged it in, Jesus appeared to bleed from the head.

I find the house, a dilapidated blue and yellow row house, in a neighborhood that is now Hispanic. Before they lived there, my great-grandmother’s family owned a pharmacy in England. So, this—along with the apostate grandfather with his Jesus pictures—is the source, the first stop of my American Jewishness. And yet I feel nothing. No sweep of history. No connection to it. I head back to Rothapolooza, as some people have been calling it, with no greater insights.

In the next session, actor Morgan Spector reads Roth’s 1959 short story “Defender of the Faith.” Waiting for him to begin, I hear someone say, “Trump is going to be arrested on Tuesday,” and I realize I haven’t read the news in two days. My only contact with the outside world has been to check in with my husband and children, who shout chaotically at me over FaceTime.

“Defender of the Faith” is long. It takes an hour and a half to read aloud. Former governor Jon Corzine is present again. He has been at many of the panels. It has begun to feel like I am at summer camp with former governor Jon Corzine and the three other journalists I keep seeing around. Will we miss each other when this is all over? Will we keep in touch?

The topic of the afternoon panel is The Human Stain, a novel published in 2000 about a Black man passing as a white Jewish man. Meghan Daum, Jean Hanff Korelitz, Lauren Michele Jackson, and Hanna Rosin discuss. Could it be published today, in light of the fact that Roth wasn't Black? The panelists think so. It’s that good. The panel becomes about writing across identity.

Korelitz in particular talks about the perception among her cohort of novelists that this is now verboten in the US. She and her friends are afraid for the state of fiction. They worry about cancellation. She uses as an example her friend Jeanine Cummins, author of the 2020 border-crossing thriller American Dirt, which became a lightning rod (and subsequently a bestseller) when critics pointed out stereotypes in the book in conjunction with the fact that Cummins is not Mexican.

Daum commiserates. She and Korelitz tell anecdotes about their friends suffering under the new draconian wokeness. They compare notes about sensitivity readers. One of Korelitz’s flagged a West Indian character in her book as a Magical Negro, and this offended Korelitz, though she did end up changing it.

Their worries might be generational. These women are Gen X and I am a millennial. Sack up, I keep thinking. Write better.

Only Jackson, a fellow millennial, connects the issue back to the lack of representation within publishing. Publishers would not need sensitivity readers if they had editors from a variety of backgrounds. The Q&A goes off the rails immediately. The audience seems outraged for a variety of reasons. One guy is mad that in the movie adaptation of The Human Stain, Nicole Kidman was too good looking. Another is mad that few people of color seem to have come to the event. A lot of them are mad at the notion that writers should only write about people of their own experience.

$14.95

amazon.com

I speak to Jackson in the hall afterward, to see if it felt intense. She laughs it off and calls it “par for the course.”

Then I run into an old writer friend who was recently canceled. He was publicly accused of something he says he did not do. We have a drink in the bar next door. I make a grave error in ordering what I think is going to be a dark and stormy. Instead, it arrives in a twelve-inch tiki glass. I have to chip away at it, like Roth at the desk.

Everything seems Rothian since I’ve been at this festival, but my friend’s predicament is particularly on the nose. The public shunning. The man misunderstood. What do I do, he asks? Never write again?

Lay low, I instruct him. Go to Europe for a while. Stay off Twitter.

The final panel of the night is where I begin to find Philip Roth boring. A group of his friends talk about Roth the man. The sun sets behind them as the writer Lisa Halliday relates a quip he made in the hospital toward the end of his life. The punchline is something like, “Nurse, you’re being quite forward with me.” I find it all a little paltry—barely worth relating. He had his witticisms. He had his friends. But mostly, he had the work.

No one should do so many days of this. On the other hand, I need seven more days of this. Only then would I become abject, deprogrammed, malleable. Only then would I be ready to fully join the cult of Philip Roth, line up with the other journalists and former governor Jon Corzine to throw out my back heaving potatoes, be given my standing desk, have my hair shaved into the tonsure of male pattern baldness.

Everyone attending just one or two events seems to be having a great time. The weekend is well-done. The arts center is nice. The actors have sonorous voices. And then there are those of us attending every session. This madness is something I have chosen.

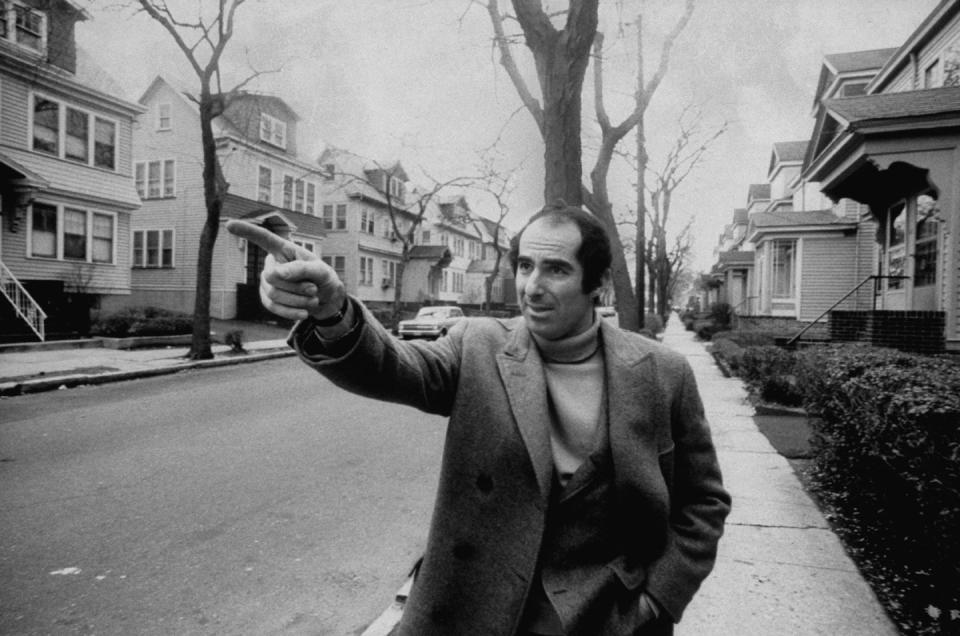

I break down on Sunday morning and eat a bagel from Starbucks before boarding the bus for the Philip Roth tour of Newark. A woman from the Newark Landmarks Committee narrates. I hear the words Lenape Indians, Weequahic High, Frederick Law Olmstead, demolition by neglect. We stop at the famed Lincoln statue. Sure enough, he’s seated. We go to Roth’s childhood home on Summit Avenue. It’s yellow and red with a faux-stone façade on the first floor, and looks much like the house where my mother grew up. Again, I feel nothing. This, perhaps, is why we need novelists and Roth in particular. To make us feel something about the lives within the rowhouses.

After the tour, I call home to see how my family spent the morning. My husband tells me that he took the kids to the mall. They got to the Build-A-Bear store right as the metal screen was coming up. The first people in! My daughter already owns a bear, but used a gift certificate to buy it a pair of jean shorts. What freedom! I bet no one talked about Philip Roth.

On my way to take the audio tour of the Philip Roth Personal Library, I listen to the Silver Jews as a joke to myself. “I heard they were taming the shrew,” sings David Berman. “I heard the shrew was you.” Rothian!

The library has Roth’s Eames recliner (it’s in great shape), a typewriter, and the standing desk. Scan a QR code and Morgan Spector takes you on an audio tour. I hear once again about the potato injury. I hear about his relationship with other writers.

There are just two events left: a reading of The Plot Against America in nine abridged chapters and a play based on Sabbath’s Theater starring John Turturro. I settle in for the former and hear the moderator say the performance will comprise three ninety-minute sessions with two intermissions. “Bruh,” I mutter under my breath. I am exhausted. I miss my kids. I read this book a few weeks ago in preparation for the weekend. It is often excellent, sometimes preposterous, but I cannot possibly sit through 270 minutes of it.

I understand why Roth, in his quest for greatness, was single-minded. Did he succeed at getting as good Joyce or Melville? He got close enough that the ambition itself doesn’t seem ridiculous. To accomplish this, he had to give his life over to literature.

Still, it’s not the only way.

In the first session on Saturday morning, Shteyngart summed up Roth’s work: “There’s all this beauty that’s been handed to me. Why does there have to be this other stuff?” In the NJPAC theater, the first two readers are great. Michael Benjamin Washington is engrossing. Eric Bogosian has a funny, deadpan delivery. But, ever the slacker, I duck out early to go home to the beauty that’s been handed to me. Roth had his ambitions and I have mine.

You Might Also Like