Why the Rib Sandwich is a Delicious Barbecue Oddity

This summer, while traveling through Tennessee for the latest edition of The South’s Top 50 Barbecue Joints, I got reacquainted with a menu item that I’ve always thought to be a bit of a barbecue oddity: the rib sandwich.

We’re not talking sliced prime rib on a brioche bun or deboned pork pressed into a patty, and certainly nothing with a “Mc” in its name. In many parts of the South, a rib sandwich is exactly what it sounds like: a small slab of pork ribs placed bones and all between two slices of plain white bread and slathered with tangy sauce.

St. Louis and Memphis seem to be the twin capitals of rib sandwiches, for the sloppy delights appear on barbecue menus all around each city. At C&K Barbecue in St. Louis, there are two sandwich options: rib tips or the city’s eponymous St. Louis style ribs, and both are piled on white bread and soaked down with the restaurant’s sweet and spicy red sauce.

You can get a rib tip sandwich at SmokiO’s, too, or, if you are so inclined, order a combo rib tip and pig snoot sandwich—a creation unique to St. Louis. Adrian Miller, author of Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine and the forthcoming Black Smoke: African American Adventures in Barbecue, has been trying to confirm reports that some St. Louis joints top their rib sandwiches with potato salad, which sounds delicious to me. So far he’s come up dry, but if anyone out there knows where one can find that variant please give me a shout.

Rib sandwiches are even more prevalent in Memphis, with A&R Barbecue, Payne’s, Jim Neely’s Interstate Barbecue and the Tops chain among the many spots where they can be found, and many are topped with the city’s signature yellow coleslaw. At other Memphis joints, like Cozy Corner, there isn’t an explicit rib sandwich on the menu, but each order of two, four, or six bones of ribs come with slices of white bread on the side, so you certainly make your own.

Perhaps my favorite rib sandwich of all can be found an hour east out of Memphis at Helen’s Bar BQ in Brownsville. Instead of white bread, this one comes on a hamburger bun, and as you gnaw around the bones you get a big hit of wood smoke and a dose of fiery heat from Helen’s secret-recipe hot sauce.

There is no tidy way to eat a rib sandwich, so don’t even try. If you pick the whole thing up and take a bite, you’re likely to chip a tooth or send half of the ribs shooting out the back. It’s better to just get in there with your fingers. Tear off a corner of the top slice of bread and use it to slip a little meat off the bone, fold it into a tasty little morsel, and pop it in your mouth. The bottom slice can be used at the end to mop up all the remaining sauce and scraps of meat.

I have long suspected that the rib sandwich originated as a collusion between stain treatment manufacturers and the National Association of Dry Cleaners, but I’ve not been able to substantiate that.

Instead, it may have originated as a practical joke. The first written reference I’ve found appeared in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1896. It relates a prank played against one Dr. Thompson, a physician at the St. Louis Dispensary, who found in his lunch pail a tempting looking sandwich and took a bite. “There was a sound as of crunching bone,” the Post-Dispatchreported, “a yell of pain, followed by anathemas hurled at the head of the idiot who had so little sense as to make a spare-rib sandwich and not label it with a warning to look out for the bone.”

Before long, though, people were knowingly eating pork ribs in sandwiches. By the 1920s, spare ribs had become a popular item at the many barbecue stands that were popping up on street corners and roadsides all over the country, especially in the Midwest. Very quickly, it seems, proprietors to start serving them between slices of bread.

In 1928, Kansas’s Emporia Gazette celebrated “a new American contribution to international cuisine—the barbecue rib sandwich.” Noting that it had evolved at the roadside stands that served, “the flivver tourist,” the newspaper described the sandwich as follows:

A handsbreadth of pork ribs thinly overlayed with fat, roasted over a hot fire until the outside is just sufficiently scared to retain the juices of the meat without hardening or drying its rich texture, generously peppered, touched with mustard, smothered with catsup or A1 sauce, served crackling hot between two slices of rapidly toasted fresh bread, and washed down with a flagon of near-beer.

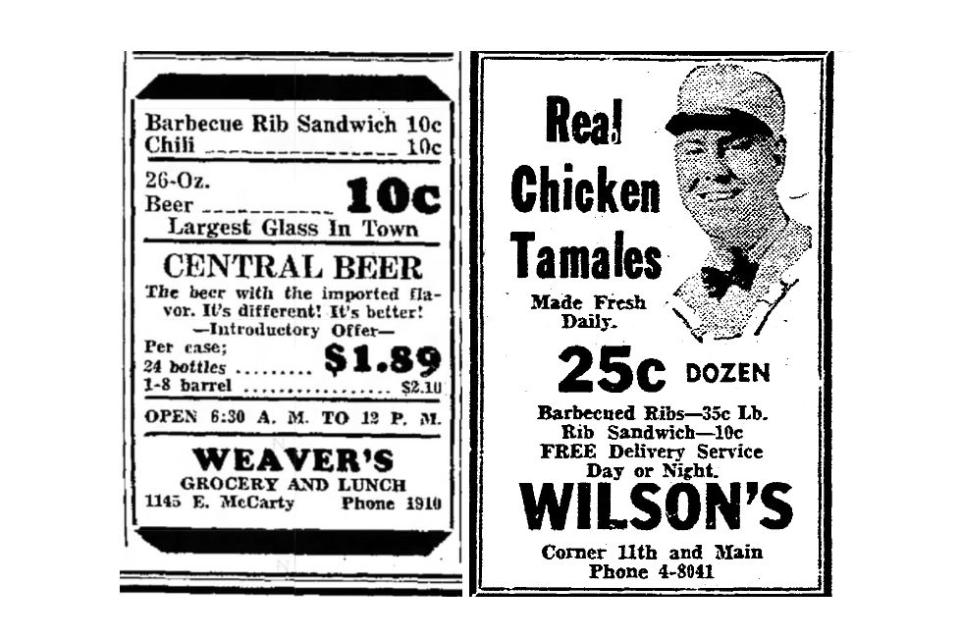

By the 1930s, rib sandwiches were being advertised at barbecue stands, cafes, and even department store lunch counters all over the Midwest, and they were making their way southward into Arkansas, Texas, and Kentucky, too.

The days, a rib sandwich is much more of a Southern thing than a Midwestern one. Almost all of the places I’ve encountered them have been small, African-American-owned restaurants. (A notable exception is Bandana’s, a St. Louis-based chain that serves 3 bone-in ribs on garlic bread.)

About as far east as I’ve found a rib sandwich is Mary’s Old Fashioned Barbecue in Nashville, where they spear the top slice of bread in place with a couple of toothpicks. Two the west, you can order rib sandwiches at Simms in Little Rock and at Meshack’s Bar-Be-Que Shack just outside of Dallas in Garland. Further south, J. C. Reid of the Houston Chroniclehas tracked down a rib sandwich at Burns Original BBQ Unlike its Tennessee counterparts, the Houston version has only a modest drizzling of sauce on the sandwich itself and more in a little cup on the side for dipping.

I prefer my rib sandwiches already drenched in sauce, though, for it only heightens the stubborn character of this Southern barbecue classic: a sandwich that defies you to eat it like a sandwich and a monument to sloppy inefficiency.