Why We Should Revisit Bonfire of the Vanities

The 1980s were good to me. My career and family flourished, yet, looking back, I feel some embarrassment. So many of today’s social ills took root in that decade. Not that I was oblivious, but I was wrapped up in my own concerns. I feel similarly mixed emotions when I think about The Bonfire of the Vanities.

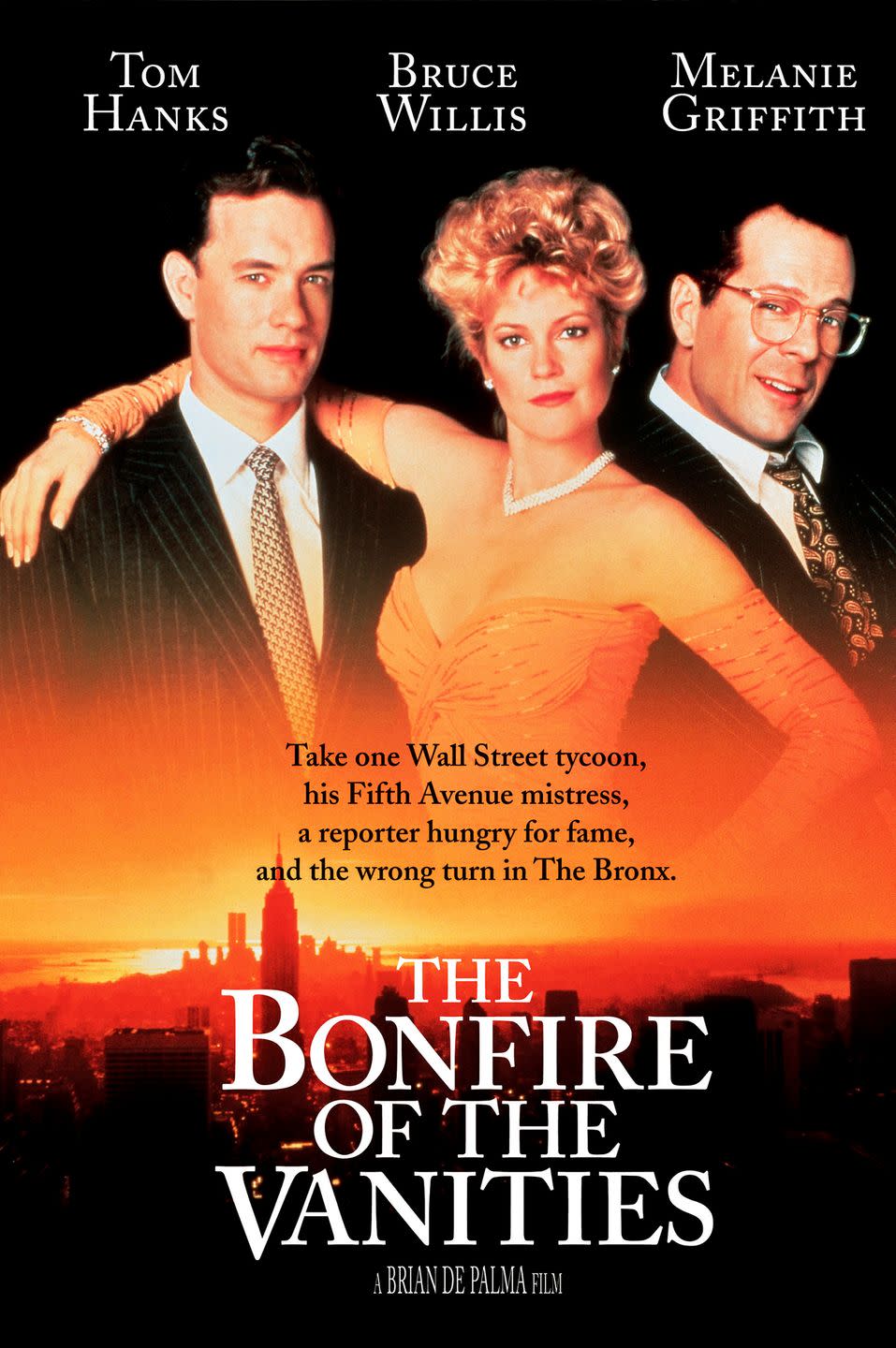

In 1990 Brian De Palma agreed to give me full access to the movie he was making—an adaptation of Bonfire, the 1987 Tom Wolfe novel that had been embraced as a metaphor for everything that was wrong with 1980s New York.

In the book, Wolfe lampooned the city’s racial politics, corrupt judicial system, rampant gentrification, barracuda press corps, and ethnic hostilities. It was high-octane social commentary as entertainment, and Bonfire became an instant sensation.

Warner Bros. hired De Palma to make a film version. But studio executives quickly developed a case of buyer’s remorse. Step by step, the story and characters were homogenized as the budget ballooned. The reviews were savage. Variety called it “…a misfire of inanities.” Good Morning America’s Joel Siegel said, “You’ve got to be a genius to make a movie this bad.” Bonfire became the movie everyone loved to hate.

My book The Devil’s Candy, about the making of the film, was published less than a year after the movie’s ignominious demise. No doubt some of the book’s success was due to Bonfire’s failure. Newsweek put it succinctly: “De Palma’s misfortune is Salamon’s gain.” Ouch. Not nice repayment for De Palma’s generosity in opening his set to me.

Now, 30 years on, the movie deserves to be reconsidered, if not for its quality then for how timely it still feels. Sadly, Bonfire remains all too relevant; only the vocabulary and technology have changed. The “masters of the universe” are now the “one percent.” Twitter has replaced the tabloids. Black Lives Matter leads the charge against racial inequity. The movie may not hold up as a great film, but it was never as bad as its worst reviews. You can watch it now as campy fun, or as a worthy artifact, reminding us that the times have changed but New York’s complicated, messy, grand machinations haven’t.

If anything has changed, it’s Hollywood. In 1990 there were movies and there was network television, with the former being considered decidedly superior.

It wasn’t until The Sopranos came along, in 1999, that long-form series on TV became serious rivals to movies. Bonfire’s many layers would work far better as one of today’s limited series.

Back in 1990 Wolfe was anticipating the future, though he didn’t know it at the time. “It’s too bad movies don’t run nine or 10 hours,” he told me. “The way I constructed the book, almost every chapter was meant to be a vignette about New York as well as something that might advance the story, and to me one was as important as the other.” Amazon Studios bought the rights to make an eight-episode adaptation of the book in 2016, but a series has yet to appear. Indulging its overindulgence, Bonfire has important things to say. Maybe we just didn’t listen closely enough last time.

This story appears in the December/January 2021 issue of Town & Country.

You Might Also Like