Why Protecting Black Cemeteries Is Integral to Preserving American History

While growing up in the 1970s, Margott Williams heard stories from her mother about her family members buried in Houston’s Olivewood Cemetery, but it wasn’t until her grandmother died in 1999 that she attempted to visit it on her own. “I never imagined in a million years that Olivewood would be so overgrown to the point that we couldn’t even get in,” says Williams. “I decided in that moment that this cemetery needs to be taken care of.”

She reached out to the county historical commission to inquire about preserving the site, but was told to start cleaning up the cemetery on her own. Though this may seem like an odd suggestion coming from a historical commission, the lack of preservation support for Black cemeteries and burial grounds is not uncommon.

Unlike predominantly white cemeteries across America, which were designed as garden spaces to honor both the dead and the living, Black cemeteries—much like Black communities—were relegated to the most undesirable neighborhoods or parcels of land.

Brent Leggs, executive director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund and senior vice president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, says, “Many Black cemeteries were located in less desirable locations which made them difficult to access, and along with the migration of Black communities from the rural south and other rural locations, that led to abandonment and neglect.”

Black burial sites have been—and continue to be—neglected by local officials or desecrated by development, leaving descendants unable to locate or visit their ancestors’ resting places. Because historic Black cemeteries are not well protected by law, local communities continue to rely on their own volunteer efforts to honor these hallowed grounds.

After years of toiling alone in the cemetery with occasional help from volunteers, Williams connected with fellow Olivewood descendant, Charles Cook. In 2004, they founded the nonprofit Descendants of Olivewood to preserve the legacy of the cemetery. In 2008, they were granted guardianship of the cemetery.

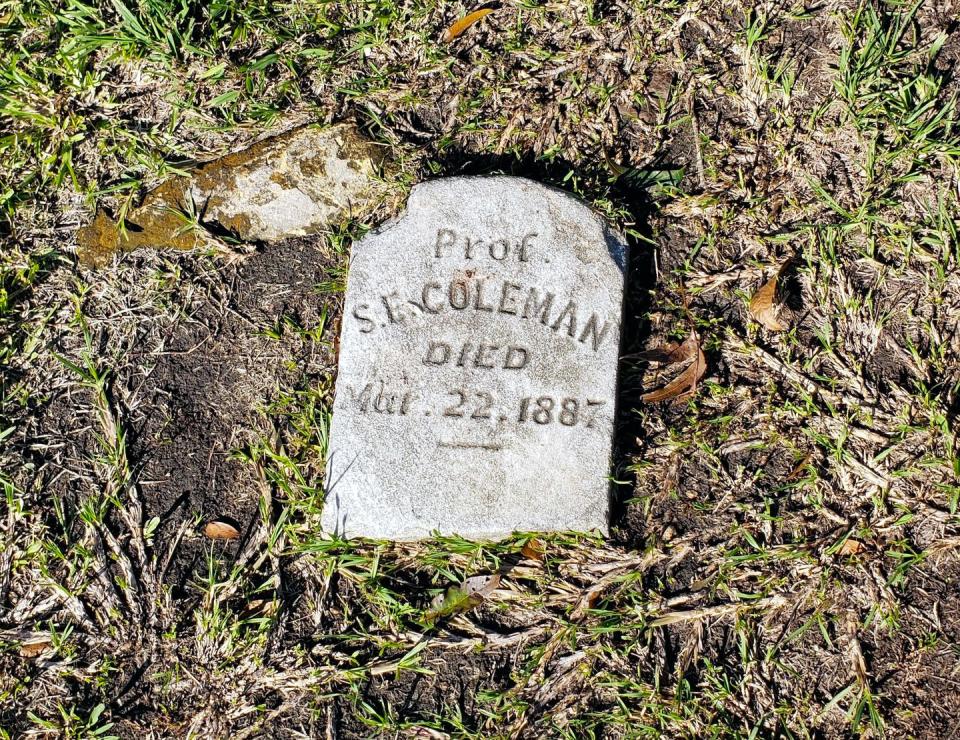

Olivewood Cemetery is the oldest Black burial ground in Houston. It was incorporated in 1875, just a decade after enslaved people were emancipated in Texas on June 19, 1865. There are over 4,000 people buried there, including figures integral to shaping the city of Houston such as Houston’s first Black alderman and cofounder of Emancipation Park, Richard Brock, and Dr. Charles B. Johnson, creator of Houston’s bicentennial song Houston is a Grand Old Town. Alongside these notable names are mothers, fathers, grandparents, siblings and children that help tell the story of America. Without the work of people like Williams and Cook, they could have ended up completely forgotten.

“So many African Americans pass our history orally, and cemeteries are one of the only ways we can walk in the footsteps of our ancestors,” says Williams. “Headstones tell the story of how towns, cities and nations were built.” She recounts seeing the burial plot of a husband and wife whose memorial read that they were brought to the United States from Africa during slavery, the headstone of a man who was a famed Buffalo soldier, and a mother and child who died during childbirth with the headstone dedication: “Think of what a wife should be. She was that.” The cemetery is also filled with expressions of West African tradition: upright metal pipes that border graves, reverse writing on some markers, and seashell designs on stones.

Though the cemetery has largely been restored, Olivewood is now under a different threat. For more than 10 years, flooding and erosion have plagued Olivewood, unearthing remains and destroying burial plots entirely. The flooding and erosion is due to both natural and unnatural causes: its location near White Oak Bayou which routinely floods during hurricane season, and commercial development runoff in the neighborhood that surrounds the cemetery. In the summer of 2021, Descendants of Olivewood received a $50,000 grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund to work with civil engineers to create a master drainage plan to prevent further damage and hopefully offset the effect of climate change. The drainage plan was recently completed, and once the design memo and cost estimates are approved, work can begin.

“Black cemeteries are sacred spaces of cultural memory where a nation can honor and remember lives once lived,” says Leggs. “At this moment, historic preservation is ascending as an essential methodology for repairing past injustices and shaping equitable futures, including prioritizing the rescue and recovery of these sometimes hidden but often significant historic cemeteries.”

Volunteer-turned-board member, Paul Jennings, received the link to the grant from his wife after expressing a desire to “step up” during the racial awakening of June 2020. He chose to focus his energy on Olivewood because of Juneteenth, the now federal holiday commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans that originated in Galveston, Texas. “We have about 500 people buried in Olivewood who were alive on June 19, 1865,” says Jennings. “In 2020 there was a lot of discussion about making Juneteenth a federal holiday, and at Olivewood we have a place where people can visit the graves of those who were alive back then. We have to protect that.”

Although this work at Olivewood and so many other African American burial grounds—including Friends of the East End Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia and Anderson Cemetery in West Virginia—has fallen on the shoulders of volunteers over the years, that may change. Newly proposed legislation, the African American Burial Grounds Network Act, intends to create a network of Black cemeteries and a formal database of historic Black burial sites—including grant funding for research and restoration—under the purview of the National Park Service. Support from the park service could increase visitation at these sites and tell the full story of America.

“When we start to look at a national collection of Black cemeteries, the amount of stories imbued in these landscapes tells a story of Black America and how we have helped to birth our democracy through unimaginable sacrifice,” says Leggs. “It's also about remembering and uplifting the achievements of Black Americans and reminding us of our social responsibility and our potential as citizens of this nation.”

In the meantime, the local advocacy work continues. Descendants of Olivewood plans to resume volunteer sessions on the first and third Saturdays, and they eagerly await the return of their annual Juneteenth celebration complete with guided tours of the cemetery. There are larger goals as well, including creating a database of the burials at the site, so family members can locate the souls buried there. Jennings and Williams also hope to raise at least $2 million to $3 million in funding through donations and partnerships to restore the damaged monuments within the cemetery and develop the landscaping. They envision it as a park and museum that can one day honor their local history and serve as an example of preservation work for future generations.

For both Jennings and Williams, looking to the past is the main way to prevent being misguided in the future. “As African Americans, it’s so important for us as individuals to know where we came from,” says Williams. “If you don’t know where you come from, you won’t know where you’re going.”

You Might Also Like