Why Pandemic-born Multibrand Platforms Move Away From ‘Sustainability’ Label

The latest players in the sustainability space may be moving away from labels — the very kind that get companies in hot water for greenwashing.

Industrie Africa, which launched its e-commerce platform amid the pandemic as a global destination for luxury fashion from Africa, is one company that’s thinking of things differently.

More from WWD

The platform prioritizes an agile marketplace with no markdowns, seasonless and made-to-order fashion. Some 30 percent of its customer base is from Africa, with 70 percent female customers around 25 to 35 years old. The U.S., U.K. and Europe are Industrie Africa’s other key markets.

Despite rejecting the label of being a “sustainable luxury platform,” Nisha Kanabar, the founder of Industrie Africa, believes creating the ultimate sustainable shopping destination is, she said, “really about offering an informed, integrated and awareness-driven experience because sustainability is transparency in a nutshell if you’re a retailer. [As a business,] you make sure you’re speaking about things in the right way and showcasing things through a certain lens and embodying your values.”

Still, some labels are somewhat hard to shed in the age of greenwashing. To inform customers, green leaf sustainability badges appear on a little more than half of the designer pages, although African designers, broadly, have long-ingrained regenerative practices, zero-waste design and slow production. Creatives like South African designer Thebe Magugu, Zimbabwe-based hand-craft jeweler Patrick Mavros and Studio 189 display such badges on Industrie Africa’s website.

Badges are broken down by “environmental” (brands that reduce water, use low-impact dyes, natural fibers), “ethical” (brands that pay fair wages and have ethical workplaces), “artisanal” (brands that support local talent and craft) and “recycled” criteria (brands that design with circularity in mind and employ repurposed material).

In the quest to be the “ultimate service storefront,” Kanabar has made the platform a place for storytelling with Imprint (a blog) and the Connect educational platform. Tapping into her publishing roots (including a stint at Vogue India), Kanabar wants to grow Connect to be a go-to platform for the industry with a dedicated source of knowledge for “next-generation aspirational fashion professionals.”

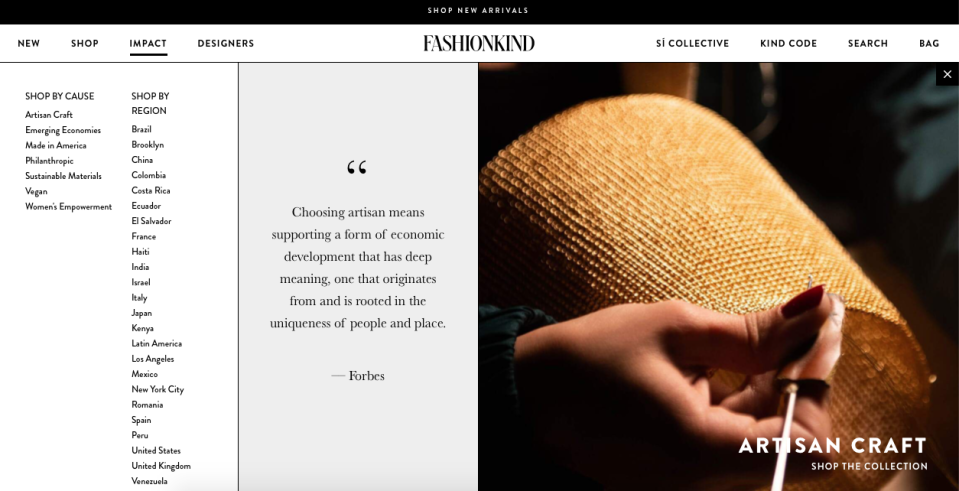

Similarly, Fashionkind, cofounded by actress Sophia Bush and Nina Farran (which launched officially in 2014) is ditching the “sustainability” thing going forward.

“We’re moving away from the word ‘sustainability’ in favor of ‘impact,’ because we like to take a more holistic view,” Bush said. “It’s not just about the environment. The concept of impact is also more tangible and connects directly to how we vet our brands. We look for brands that have integrated positive impact into their business model (philanthropy and purchasing carbon offsets aren’t enough).”

Like many others, Fashionkind wants to transform the luxury experience, becoming the one-stop destination and driver of “change in the industry by bringing back the true soul of luxury in human connection and the thrill of discovery.”

Fashionkind vets potential designers according to what it calls the “Kind Code.”

“First, we look at a series of design criteria, after which we evaluate impact, looking at people, places, processes, materials and initiatives,” Farran explained. “For us, transparency is about knowing the story and intention behind your product, which we consider to be the ultimate luxury.”

Early on, the company pivoted into drop ship and made-to-order fulfillment models, moving further and further away from “traditional retail” to cut down on its environmental footprint.

Despite technology being an advantage of sustainable luxury platforms today, the obsession with “curation” and “customer service” is not so distant from the department store model — yet today, there’s a marked difference according to the cofounders.

“Our customers can also shop by cause (Artisan Craft, Emerging Economies, Made in the USA, Philanthropic, Sustainable Materials, Women’s Empowerment, Vegan) and by region (Colombia, India, Venezuela, New York City, Italy, and 19+ more),” Farran said. “Personalized customer service is a core area of investment for us, which cuts down considerably on returns and helps us foster deeper connections, build personal relationships and create community.”

Sustainability platforms are evolving when it comes to how they measure impact.

Last year, Fashionkind launched an initiative with Si Collective, onboarding 21 designers from Latin America whose orders were canceled unexpectedly by retailers at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and were left with excess inventory and no place to turn. “The partnership was a tremendous success. Our business saw its best year yet, and our designers were able to continue to provide stable income for their artisans while preserving their traditional craft. It was a powerful example of what can happen when impact and business collide,” Bush said.

As with Fashionkind, The House of LR&C, (which stands for love, respect and care), launched in December 2020, prefers “impact” to sustainability.

The retail concept founded by husband and wife duo, Seattle Seahawks quarterback Russell Wilson and singer Ciara, and former Lululemon chief executive officer Christine Day. Brands like in-house streetwear label Human Nation (made with 100 percent organic cotton and polyester) anchor the e-tailer.

Pending B Corp certification, Therese Hayes, chief sustainability and business development officer for The House of LR&C, said, “We focused our efforts on those areas where we would have the greatest impact — the concept and creation stage. We created what we call ‘the Goods Mandate’ to guide our design and production teams in selecting materials that have improved social and environmental impacts that lines up with the preferred materials defined by the Textile Exchange.”

While the company does not disclose material mix and has yet to achieve goals on clean energy and partnerships, The House of LR&C employs 100 percent recycled or compostable packaging and donates 3 percent of net revenue to support underserved communities through the Why Not You Foundation. A take-back program is currently in the works.

“All brands in the House of LR&C must meet a threshold level of products that meet better and best criteria. We also focus on the consumer use phase as it is responsible for a large percentage of the life cycle impact by creating quality products that will last and be passed along through our Community Closet initiative,” Hayes said. “We invite our consumers to participate in our sustainability efforts by incorporating technologies that repel liquid, odor and stains, so our products can be washed less often.”

Even while start-ups can imbue better practices from the start, the platforms are finding themselves discovering what age-old retailers already know — there’s never an end destination for sustainability.

“Our philosophy is to keep it simple and consider sustainability at every stage, from design to recycling,” Hayes said. “We focus on areas where we can make a real difference, and are sure to communicate our vision and efforts truthfully and in plain language. Sustainability is an ongoing journey, we are committed for the longterm and excited by the knowledge that we will never ‘arrive.’”

Sign up for WWD's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.