Why More Men Than Ever Are Getting Hair Tattoos

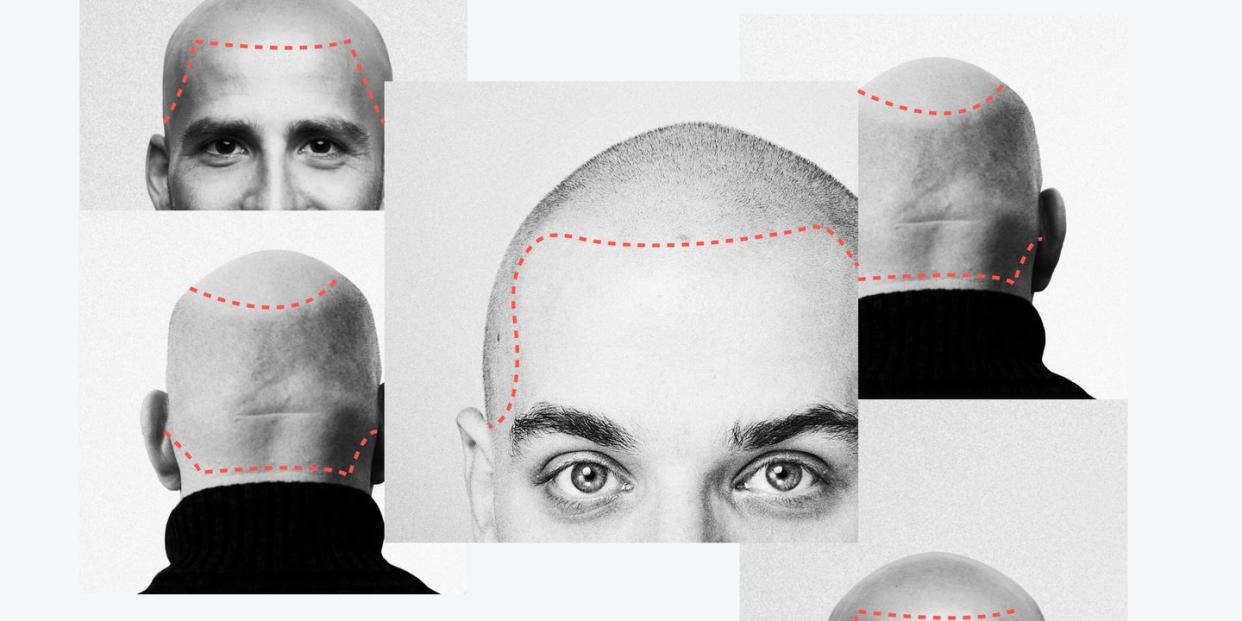

On a cold morning in a quiet trading estate near Accrington, Joseph Lanzante places a bendy ruler on a bald man’s head and, with a white pen, carefully marks where his client’s hairline used to be. It's two weeks before lockdown, and the only PPE in the room is the bin-liner aprons worn by two watching trainees. “You’ve got to get the lines right,” he warns, dipping his bandage-wrapped tattoo gun in a pot of black ink and poking at the tension in the air, “because the rest is just filling in.”

For more than three years, barbers and beauticians from across the country have travelled to the Joseph Lanzante Training School to learn scalp micropigmentation (SMP): the process of tattooing tiny dots on the head to create the illusion of stubble. Today, three men – one bald, one balding and one boldly holding on after three hair transplants – are set to be worked on by the teacher and his students.

Scalp micropigmentation is but one fast-growing branch of the booming male hair loss industry, which is set to be worth well over $45 billion worldwide by 2025. According to the International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery, a non-profit medical association of more than 800 hair restoration doctors, the number of men paying for hair transplants – the most expensive and invasive of the male pattern baldness treatments – rose 60 per cent from 2014 to 2016. Others have flocked to hair loss start-ups like Hims and Keeps, which have imbued hair-growth supplements with a previously lacking sense of cool courtesy of Instagram-savvy ad campaigns (sample strap-line: "handsome – is no longer genetic"). Meanwhile, 3D microfibres, which are combed through thinning strands to create density, continue to rise in popularity. Then there's the surprising re-emergence of male wigs.

Which all might have you wondering: why now? Is SMP really the answer to male pattern baldness? And why do we need one in the first place?

“Let me tell you, don’t go to a therapist – go to a barber. They’re cheaper.”

Lanzante is leading me around his long white-walled studio, past black leather barber chairs and bird’s-eye portraits of dotted scalps. “On Saturday my first three customers had split up with their wives," he continues. "One guy wore a baseball cap his whole life. I should get paid extra.” As a veteran barber and balding man, the 61-year-old has an intimate understanding of how confidence-sapping hair loss can be – and how potentially lucrative its cure.

Lanzante is always on the look-out for a new business venture. He claims to have spearheaded no-reservation salons and beard grooming services in the UK, the financial success of which left him walking around like a “dog with two dicks”. Five years ago, while on a research trip to America, he discovered that hairdressers across New York were practicing scalp pigmentation. He knew he needed to get some SMP training for himself. The problem was, the only teachers available were beauticians, who were mainly experienced in microblading eyebrows and lips to look fuller. They didn’t understand male hairlines or fading techniques. Spotting a unique opportunity, he launched his own course and service in 2017. “Nobody in the [British] barbering world or on Facebook knew about micropigmentation until I put it out there,” he says.

A full scalp procedure plays out like this: the SMP artist will mix black ink and water to create one of 32 different follicle shades. Then they plot out your hair line (“Get that wrong and it’s game over,” says Lanzante) and implant micro-dotted ink patterns into the scalp with an ultra-thin needle, to give the appearance of shaved hair follicles. During two three-hour follow-up sessions, they add density and fix any problems. In total it costs up to £3,000 and should last for around two years before it begins to fade. The procedure is particularly popular amongst those with visible scarring, as well as alopecia sufferers and people undergoing chemotherapy. Lanzante tells me about a recent client with cancer who burst out crying after seeing the results.

It’s an hour into my visit before I realize that Lanzante has gone under the needle himself. “My wife didn’t want me to have this done,” he says, measuring up another client’s forehead. “But I said, ‘I have to if I’m selling it.’ Afterwards, she said it was the best thing I’ve ever done. It just changed the whole look of my face.” He laughs and slaps his client on the shoulder. Colin*, a burly 62-year-old, has a wispy crescent of curly hair that grows thinner as it scales his head. “You might even get laid."

Colin chuckles sheepishly and fidgets into his chair. “My wife is concerned, but I’ve spent a long time considering it,” he says. It's a good thing he has, as Joseph wastes no time in buzzing the remaining hair off Colin’s head and getting to work, rhythmically injecting dots of ink into the shallow layers of his scalp. Does it hurt? Not really, but it’s uncomfortable; a bit like wearing a cheap, shaggy jumper. Do his friends know he’s having the treatment? No, but they’ll find out later when he arrives for their weekly curry night. He’d researched other methods but opted for micropigmentation after his brother had the same procedure. “I’ve seen a few people who’ve had hair transplants done and it just doesn’t look right. It’s too thin.”

While Colin took the less invasive route, a rising number of men are spending up to £30,000 on surgical hair grafts in a bid to battle male pattern baldness, with no guarantee of short or long-term success. A study last year suggested that men are losing their hair at a faster rate than ever before (Chinese state broadcaster CGTN described hair loss among the young as an "epidemic") and interest in transplants has grown alongside advancements in surgical techniques. Candid endorsements from celebrities like Wayne Rooney have normalized what was a fringe treatment—in September 2020, Manchester City announced a partnership with Istanbul's HWT Clinic as the club's "official hair clinic partner"—but few people seeking out treatment are on footballer’s wages.

Inevitably, that's created a market for cheaper, occasionally dangerous alternatives, predominantly in Turkey, where its world-leading hair transplant industry has inspired unregulated practitioners to set up shop in its shadow. Lanzante says he is often tasked with disguising the subsequent scarring. The words ‘head tattoo’ and ‘sensible’ rarely appear in the same sentence, but in an industry beset by malpractice and false promises, micropigmentation could be one of the least extreme options.

But why is it even an option in the first place? The American Hair Loss Association describes going bald as a “devastating disease of the spirit” that affects “nearly every aspect of life”, and the organization’s founder, Spencer Kobren – who also hosts The Bald Truth radio show – believes male hair loss is the last bastion of politically incorrect culture. “For whatever reason, people can still poke fun at guys dealing with hair loss,” he tells me. “About two-thirds of men suffer it by the age of 35. That makes us extremely vulnerable to all of the really terrible things that happen in this industry.”

Over the past year, his radio show has been inundated by calls from men complaining about their botched hair transplants, performed by unlicensed practitioners in Turkey and India. “There's always been the walking wounded of the hair transplant industry, but that has now scaled to proportions that I’ve never seen in my 22 years of experience,” he says. “More young guys from the UK are walking around disfigured by bad surgery, and unfortunately their lives in many cases can be destroyed.” It’s perhaps understandable that black market practitioners would target the UK – last year, a survey of 10,000 British men found that a majority would rather have a small penis than lose their hair. Other studies have found strong links between hair loss and depression, as well as problem drug use and low sex drives.

Ironically, rising rates of stress around the prospect of going bald could at least be partially responsible for any increase in millennial hair loss.

In that regard, Kobren thinks the rise of social media has a prominent part to play. In the sense that we constantly compare ourselves to other people, but also due to the endless, data-driven hair loss ads that are targeted at young men. “My entire mantra is acceptance is really the best cure for hair loss,” he says. “Unfortunately, I deal with the majority of men who are not equipped to deal with hair loss. People say that men shouldn’t be concerned about it, but that’s just not the reality.”

According to Kobren, who is a keen proponent of hairpieces, it’s not just the hair transplant industry that is beset by bad practice. “I'm not gonna be loved for saying this, but the majority of scalp pigmentation work that we see here in LA is really, really bad,” he says. “It’s very prevalent in the US. You can walk by almost any hair salon now and they're offering it, and I could step outside and see at least two or three guys that have noticeably bad SMP.” Kobren believes that ‘tricopigmentation,' a variation of the procedure that uses more temporary inks, is a better option, but he has serious doubts about the technique as a whole. “Can it look good? Yes. Can it be done correctly? Yes. If someone is well-educated and well-informed, they can have a decent experience. But it's rare.”

YouTube can attest to that. There, you’ll find stories of regret from men who put their trust in the wrong artist, and ended up with jagged, blue-tinged botch jobs. One video, ‘I GOT A HAIR TATTOO AND I REGRET IT!’, by American-Palestinian vlogger and actor Yousef Erakat, has racked up nearly six million views. He talks about how his previous experiences of SMP had been positive, until a trip to a salon in New Jersey plunged him into a depression. “It was the most painful five hours of my life,” he tells the camera, light bouncing off his too-dark dome. “When I first got it done it was pitch-black.” It soon became clear that she’d not only used undiluted tattoo ink, but that she had also performed the treatment with a full-sized tattoo needle. His only option was to have the whole procedure lasered off.

For Lanzante, protecting clients’ mental health is paramount. “We have a duty of care, and you’ve got to know when to stop, because customers often don’t,” he tells me. “You have a lot of customers who see things that you can't see. If I was to carry on doing it every month, after a year it would like I've just painted it on. He’d look like a Lego man.” Sometimes, Lanzante admits, he has to pretend that he’s applying new ink to those who won’t take no for an answer. Kobren refers to this kind of obsessive behavior as “hair greed” and warns that “most practitioners aren't as caring.”

Lanzante doesn’t offer facial hair procedures, but other practitioners do. Ravi Sabharwal, of the Harley Street clinic Scalp Provoco, has noticed a rise in men with patchy beards asking for micropigmentation on their cheeks and jawlines, though he warns against getting the whole shebang. “You’d have to be a brave person to get a full beard tattooed on a clean face,” he tells me. “I’m giving the look of a hair follicle, of 0.1-millimetre stubble. We can add density, but we can’t replicate a long, three-dimensional hair. We’re going for the natural look.”

Rene’e Cleovoulon, of the London Dermatology clinic, has also seen an increasing number of men asking for beard treatments. “My clients are usually people who have difficulty growing facial hair or have nothing at all,” she tells me over email. “Facial hair grooming in general has in recent years become very fashionable, so being able to improve it […] is appealing.” Cleovoulon believes that micropigmentation will eventually become an essential part of male grooming. “For some men it can be a fantastic, low maintenance, non-invasive solution to a big problem. It literally gives back confidence.”

The Covid-19 pandemic forced Lanzante to shut down operations for six of the past twelve months, but he's still getting plenty of enquiries for micropigmentation procedures and training. The National Hair & Beauty Federation recently revealed that British barbershops and salons are collectively losing over £16 million a week under lockdown, but Lanzante is hopeful. "People will always want to look good," he reasons.

In the Ebers Papyrus, the first known Egyptian medical journal, written around 1500 BCE, men with hair loss were advised to apply a mixture of scorched hedgehog prickles, fingernail scrapings, honey and alabaster. Like many other ancient societies, Egyptians considered baldness to be a sign of servitude, or immorality. The threat of discrimination also drove people to spread lion, hippopotamus, crocodile, cat and serpent fat across their heads, and things would only get more stomach-churning. Balding Romans would smother themselves in chicken dung, ground-up mice and horse teeth. Greek physician Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine, opted for mixtures of pigeon poo, horseradish and opium.

Even Julius Caesar couldn’t escape ridicule for his bald spot. He would comb his wispy hair forward and ensured that all coins concealed his shame. Roman biographer Suetonius claimed that he took the “scoffs and scornes of back-biters and slaunderes […] exceedingly to heart”, and that “of all the honors voted him by senate and the people, there was none which he received or made use of more gladly than the privilege of wearing a laurel wreath at all times.” But public perception was shifting. Caesar's prolific sexual appetite – which had earned him the nickname ‘the bald adulterer’ amongst aristocrats and peasants alike – helped to rebrand baldness. Teamed with Hippocrates’s earlier observation that eunuchs didn't lose their hair – so hair loss must, in some way, be linked to functioning testicles – baldness and virility soon became synonymous.

It's an association that continues to this day, and it’s not the only positive PR job that’s been attempted over the years. Many 19th century doctors in England publicly attributed baldness to high intelligence, with one 1886 medical record using the New York Stock Exchange as evidence (“a mob of shining pates belonging, as a rule, to rather young men”). The assertion stuck, and a Californian newspaper stated in 1953 that bald men were “a step ahead of the others on the evolutionary road,” arguing that rising educational standards would eventually eradicate hair altogether. Sixty-six years later, a study by Barry University found that bald men were more likely to be perceived of as intelligent, wise and of “high social value” by women.

But it wasn’t all so flattering. Amongst western doctors, one of the most prominent theories was that men’s hats were to blame. “Baldness is a condition brought about almost solely by the tight hatband and the heavy hat,” wrote Dr. JO Cobb, a surgeon with the US public health, in a 1909 issue of the New York Times. “Among semicivilized peoples it is nearly unknown, and especially is this true of the dark races. Old Indians and old negroes seldom are bald, unless they have adopted the white man’s stuff hat.” Some believed baldness was contagious. Others pointed fingers at pollution and short haircuts. In 1954, Dr Hans Elias of the Chicago Medical School blamed thin scalps, in an article that asserted, “the hair-bearing human is the fat head.”

While the experts argued, salesmen got to work.

The 19th century was a boom time for pricey panaceas. In the west, snake oil tonics gave way to herbal treatments, which were then discarded for new-fangled tech in the mid-20th century; devices with names like ‘Thermocap’ and ‘Xervac’, the latter promising to suck the hair out of your stubborn scalp like a hoover.

Then, in 1988, an experimental hair loss drug, called Minoxidil, was approved by the American Food & Drink Association. Rebranded as Rogaine, it was the first intervention in 3,500 years that actually worked. But the true game-changer – one of the seeds from which much of the men’s wellness industry has grown – was still on the horizon.

Finasteride is one of the few drugs proven to reverse hair loss. It is also one of the most controversial, due to the side effects that a small percentage of its users have reported – including low libido, erectile dysfunction and depression (an anxiety, incidentally, that steers people towards cosmetic treatments like SMP). First approved for hair loss in 1997, it was rebranded as Propecia and immediately flew off the shelves (sales in the US eventually peaked at $447 million in 2010). One Nineties commercial for the drug sees two men catching sight of an elegant woman sitting alone at the bar. They both approach her individually, but recoil when they discover that she has a deeply receding hairline. The advert ends with the question: “Dude, who you foolin’? She thinks the same thing about you.”

The bald head as a punchline, a source of shame and anxiety, has been the way male hair loss treatments have been marketed since Ancient Egypt. Recently, though, things have shifted; our evolving perceptions of masculinity, mental health and body confidence have created the need for a kinder, more holistic approach from pharmaceutical companies. Some millennial pink branding was never going to go amiss, either. Step forward Hims, the industry-shaking, Instagram-inspired peddler of pills, potions, pastels and male empowerment.

Focusing on treatments for hair loss (Finasteride and Minoxidil) and erectile dysfunction (Viagra and Tadalafil), as well as general wellness advice, the start-up has hit a market valuation of $1 billion. “We hope to enable a conversation that’s currently closeted,” reads the website. “Men aren’t supposed to care for themselves. We call bullshit. The people who depend on you and care about you want you to. To do the most good, you must be well.” Somewhat inevitably, other male-centric mail-order companies have followed their lead, including Keeps, Roman and British brand Numan.

Numan's founder, Sokratis Papafloratos, who started the online prescription-based pharmacy in 2018, agrees that acceptance is the best approach to dealing with hair loss. “[But] if it is a problem, there are solutions. They are safe, and we’re here to guide you.” He describes body-shaming commercials as counterproductive, and the website regularly hosts articles on mental health and male identity. “Performing the role of the man is absolutely a waste of energy and fills you with unnecessary emotional stresses that then have all sorts of knock on effects on your physiology, your psychology and your whole way of being,” he says. “Using shame, or some of the more traditional male archetypes, is quite tired. I don’t think you can go out with that message anymore, and you shouldn’t.”

The industry that once exploited male vulnerability is now tentatively preaching self-love; that the inside of your head is ultimately more important than the outside. It has also never been more successful, and it's a growth that, ironically, shows no sign of stopping. The change in tone is welcome, but it also clarifies the stark contrast between the products these companies offer. Unlike erectile dysfunction, male pattern baldness is purely an aesthetic issue, albeit one that comes with all manner of psychosocial baggage. ED requires medication, but it's possible – although difficult – to imagine a world that doesn't stigmatize hair loss at all. How far away that is is anyone's guess, but it’s clear that we’re going to need a lot more than a sans-serif sales pitch to get there.

Back at the training school, where Lanzante is trying to steady his students’ nerves with a flurry of one-liners, a middle-aged man in a checkered overcoat, tweed trousers and immaculate brown derbies appears in the doorway.

“You should talk to Graham, this man right here,” Lanzante says, springing up to greet his friend. “All his best mates didn't notice that he’d had micropigmentation for two months. Then I posted the before-and-after on Facebook, they found out and started taking the mickey out of him.”

“Oh, they really took the piss,” says Graham, resting his coat on a fold-out chair. “They do a thing on Oscars night where they dress up in tuxedos and give out awards. 'Twat of the Year' and all that. They gave me 'Best Tattoo'. Said I was hiding in plain sight. They wanted me to give an acceptance speech. They’re crackers.”

He’s here to negotiate a top-up. Lanzante doesn’t think he needs it, but the hair Graham does have grows in patches, and he thinks a darker pigment means he won't need to shave his head as often. “What that means is I’m going to have to do the whole friggin’ lot again,” Lanzante warns, flashing a few fingers to indicate the price. Graham shrugs, says it is what it is, and arranges a date.

Then comes a much-needed break. In the adjoining kitchen, two trainees pick up mugs of milky coffee and rub at their aching wrists. Chloe*, a middle-aged salon-owner with peroxide blonde hair, plans to turn one of her empty rooms into what, pre-pandemic, would have been a lucrative micropigmentation station. She’s been holding the pen too tightly out of nerves and has delved a little too deep into the scalp at points. “Suppose you get used to it,” she sighs.

Colin eventually walks over, scalp glowing red with irritation. The coloring will die down within a few days, but he tells me that he’s managed to avoid looking in the mirror anyway. At this point in his life he understands the value of patience. “I'm a great believer that if you feel good about yourself, you actually look better,” he says. Lanzante nods.

“That’s why this is all becoming so popular,” he tells me, taking a sip of tea and flashing a big, beaming smile. “It’s a confidence thing!” If there’s one thing Lanzante understands, it’s confidence.

* Names have been changed; Joseph Lanzante's training school is currently relocating to Lowerhouse, Burnley

You Might Also Like