Instagram's Favorite Cartoonist Wants to Be Famous After She's Dead

You can always go back home, Liana Finck recently discovered, but you can’t necessarily trust the new owners. The Brooklyn-based cartoonist stopped by her childhood home in Orange County, New York this summer, on her way to the Catskills with her boyfriend, and found the walls inside newly painted brown. She thought about saying something: The walls looked better white. “I don’t know,” she says. “I had so many feelings.”

The house was also smaller than she’d remembered, which led Finck to wonder about other childhood memories. What else had she gotten wrong? Finck has made a career of this kind of pointed autobiography. She is best known for her single panel, pen and ink Instagram cartoons, in which she almost reflexively discloses her worst habits (and documents others’ most obnoxious qualities). In her memoir, Passing for Human, she investigates why she’s spent most of her life feeling different from others. But the house made her wonder: Has she been an unreliable narrator of her own life? Had she misjudged her teenage loneliness, misclassified herself as an outcast? “The neighbors are very nice but [they] are all motorcycle people,” she says. “I wouldn't have friends if I lived there now.”

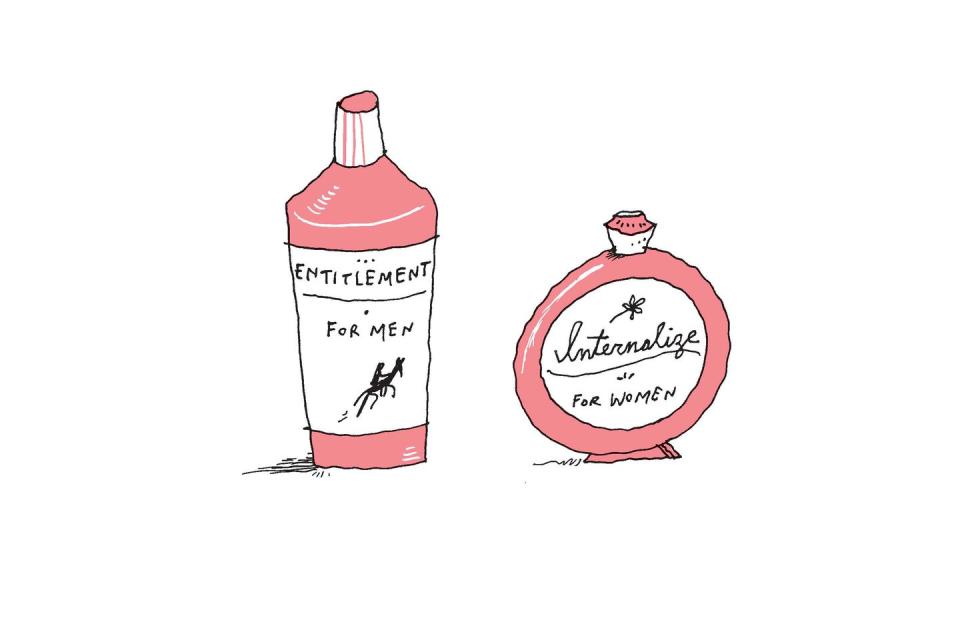

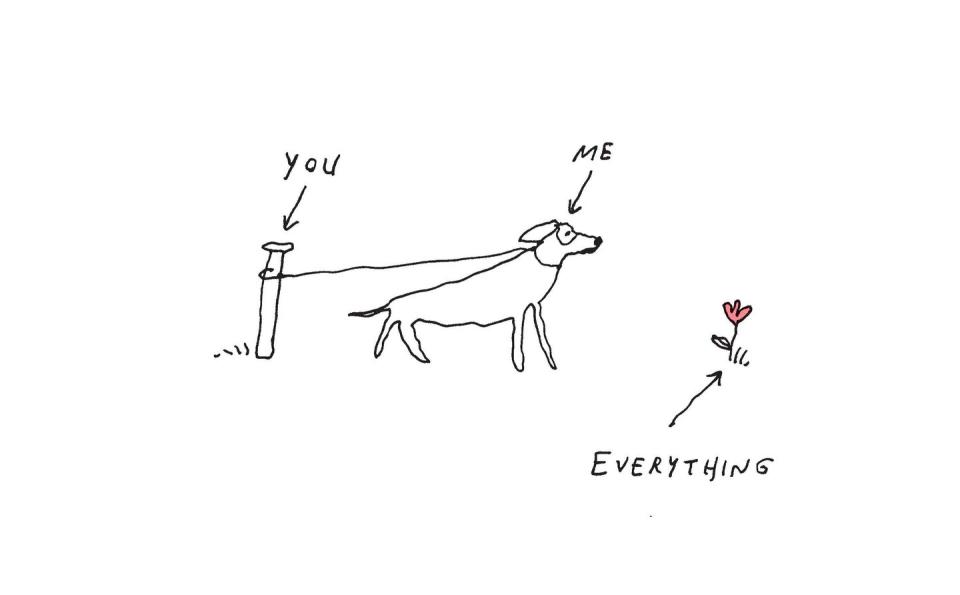

In her new book, Excuse Me: Cartoons, Complaints, and Notes to Self, Finck turns her gaze outward. “It’s me working through things that bother me, things we’re not supposed to say out loud or even admit to ourselves.” Her humor turns on ruthless observation, making light of our inflated expectations and everyday disappointments. A Venn diagram lists male authors under “known by last name,” dogs under “known by first name,” and women authors in between. In a section called “Art & Myth-Making,” a woman hunched over a sheet of paper is asked what she’s making. “Enemies,” she says, with an idiotic grin.

ELLE.com spoke to Finck ahead of her book release, to discuss her humor, the stakes of making fun of Park Slope parents, and the source of her newfound confidence.

You get a lot of rude comments on Instagram. Has that changed what you post?

Yes, it has. I avoid things that get angry feedback. I seem to get the most hatred from people without a sense of humor, who are on my side [but] who misunderstand me, like new parents. I cut down the number of stroller cartoons I draw, because I can't bear to make them angry. [But] I'm a cartoonist, I make fun of people. Park Slope is very self-righteous. You don't want to make fun of someone who's down on their luck; you want to make fun of someone who's self-righteous and pretty lucky, and I hit the jackpot.

Are you worried about the humor of Excuse Me being misunderstood?

I'm worried about it not being funny. I'm not sure it's funny—it's nuggets of emotion.

There’s one cartoon that’s a timeline from ages 4 to 32, and every few years it says “About to come into your own.” Between writing Passing for Human and Excuse Me, do you feel like you've come more into yourself or found your voice?

I do. My voice has gotten louder and deeper.

Physically?

Yes, my actual sound voice. I’ve learned when to smile and project and make steady eye contact when I deal with people, and that's the thing I was missing as a kid. I think it's also what I was missing as an artist: You need a certain feigned confidence. But I still feel lost and terrified every time I start a new project. I have very low self-confidence when I'm doing something new, and I can sink into a depression and not do anything. So I try not to do that all the time. I wish I could move and explore faster, but I'm a pretty slow explorer.

Do you have trouble knowing when you're done with an Instagram cartoon?

Only when I'm stressed out. You can tell; I get fewer likes. I drew a graph last week that said “Age” and “Potential” on the axes, and I had potential going down as you get older. People got it, but they got so angry. It really struck a nerve, and why? I didn’t mean potential is value; I meant potential as the possibilities of things you could become. When you narrow [things] down, you figure yourself out and you lose potential. But I was tired when I made that graph, and people smelled it on me.

How do you feel having published this book? As a freelancer, have you stopped feeling like your work fluctuates?

Maybe. I hope not. I want to keep feeling like change is possible. I wonder if I'll always feel like I'm about to become famous. Because that’s a great way to feel. I think the minute I realize that this is it and my income is not going to get any higher—in fact it'll probably get lower—I'll be sad.

When I say I want to be famous, I want to be famous after I'm dead, not before. But I want [the work] to keep going, which is hard in an ageist society.

You have a background in poetry, and there's this simplicity in your book that’s very effective.

I love rhyme, I love bold structures. I think I'm a simple person in a lot of ways, with childish tastes, and so I love rhyme.

I wonder if people are ever like, "What is this?" or "I thought these were supposed to be cartoons."

Yeah. What is funny? I don't know. I aim to be direct and uncover things. I hope to become funnier; I think I have funny inside of me. But there's too much urgency right now to be funny. It's hard to be both sometimes. There should be room in cartoons to be direct, and not necessarily funny.

I think I'm saying that we shouldn't keep so much in. In a way, it's very Trump-like, to let it all out. And I'm sorry about that. But he wouldn't be sorry about that, so there's the difference.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

You Might Also Like