Why Does the Tragedy of the Titanic Still Grip Us?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

This article first appeared in the April 1992 issue of Town & Country.

On the clear and frigid night of April 14, 1912, the sound of seven bells marked 11:30 as R.M.S Titanic, the world’s newest, largest and most luxurious ocean liner, cut her way through the cold North Atlantic at 22 ½ knots on her highly publicized maiden voyage from Southampton to New York. Earlier in the evening, a communication had come up into the Marconi shack from S.S. Mesaba up ahead: “Saw heavy pack ice and a great number large icebergs. Also field ice.” But the wireless operator was so busy that he shoved the message under a paperweight, and there it sat.

Although most of the American passengers traveling in First Class had left the Louis XV lounge on A Deck and retired to the warmth of their stateroom, a few gentlemen dressed in formal dinner attire lingered over snifters of brandy and cigars, chatting, reading or playing the last hands of auction bridge in the majestic Georgian smoking room. The room itself was emblematic of this voyage and this ship: “opulent” is the only word to describe it, just as “elite” is the word that best captures the status of the voyagers. Dealing cards at one table near the white marble fireplace was Major Archibald Butt, President Taft’s military aide, returning now from an assignment to the Vatican. To his left was Harry Widener, son of Philadelphia streetcar magnate George D. Widener. Across the table, the prominent Washington sportsman Clarence Moore, now the proud owner of 50 pairs of English foxhounds he had just bought for the Loudoun Hunt back home, had finished telling a story. Next to Moore sat Pennsylvania mining baron and Main Liner William (Billy) E. Carter, who was traveling with his wife, two children, maid, manservant and chauffeur. Stretching, he wondered aloud how long it would take it unload their new 25-horsepower Renault motorcar he had bought in Europe and had had stowed in the ship’s hold. Once back in Philadelphia, he would be a busy man, a man in a hurry. For now, there was nothing to do but chat idly and pass the time.

Over in the corner, Colonel Archibald Gracie, a wealthy military historian who had attended West Point, listened carefully while Charles M. Hays, president of the Canadian Grand Trunk Railroad, discoursed on the future of ocean travel. “The White Star, the Cunard and the Hamburg-Amerika lines,” Hays conjectured, “are now devoting their attention to a struggle for supremacy in obtaining the most luxurious appointments for their ships. But the time will soon come when the greatest and most appealing of all disasters at sea will be the result.” Gracie nodded politely but kept his counsel. After all, this Hays fellow was a railroad man.

Outside, the sea was flat calm and the air bitterly cold. There was no wind and overhead a blaze of stars shone on a scene of peace and serenity rare in the Broth Atlantic. It was almost 11:40. Nigh in the crow’s-nest, lookout Frederick Fleet suddenly caught sight of a dark shadow in the distance. Wiping his frosted eyes he stared again, and this time the object appeared much larger and more towering. Immediately he struck three bells, rang the first officer on the bridge and announced loudly, “Iceberg right ahead.” Then he stood watching as the ship’s bow began to swing slowly to port and the great berg scraped by on the starboard side raining shards of ice all over the deck.

To the lookout, it seemed only a close shave, but in reality, Titanic was being dealt a mortal blow. An underwater spur on the berg was tearing a jagged 300-foot gash in the huge liner’s belly.

Almost immediately, Captain Smith came rushing out of his quarters behind the bridge and asked the first officer, “What have we struck?”

“An iceberg, sir. I hard-a-starboarded and reversed the engines, and I was going to hard-a-port round it, but she was too close. I could not do any more. I have closed the watertight doors.”

Below deck at the card table Clarence Moore felt a faint jar and one of the room’s stained-glass panels tinkled. “What was that” he asked casually.

“Probably just a big wave … or maybe a whale,” replied Archie Burt. But he might have been joking.

Also noticing the tremor, a smoking-room steward quietly put down his silver tray, hurried through the aft revolving door, past the resplendent Palm Court and out onto the deck just in time to see splinters breaking off the mountain of ice as it slid by and faded into the darkness astern. Returning inside to the four curious card players, the steward leaned over and said, “Looks like we bumped into an iceberg.”

This time it was William Carter who looked up, a stark expression on his face. “I’d guess, gentlemen, that we’ve had it,” he pronounced gravely, folding his cards.

“Oh, nonsense, Billy,” Butt said, laughing. He took a puff on his cigar. “As they’ve been saying, God Himself could not sink this ship.”

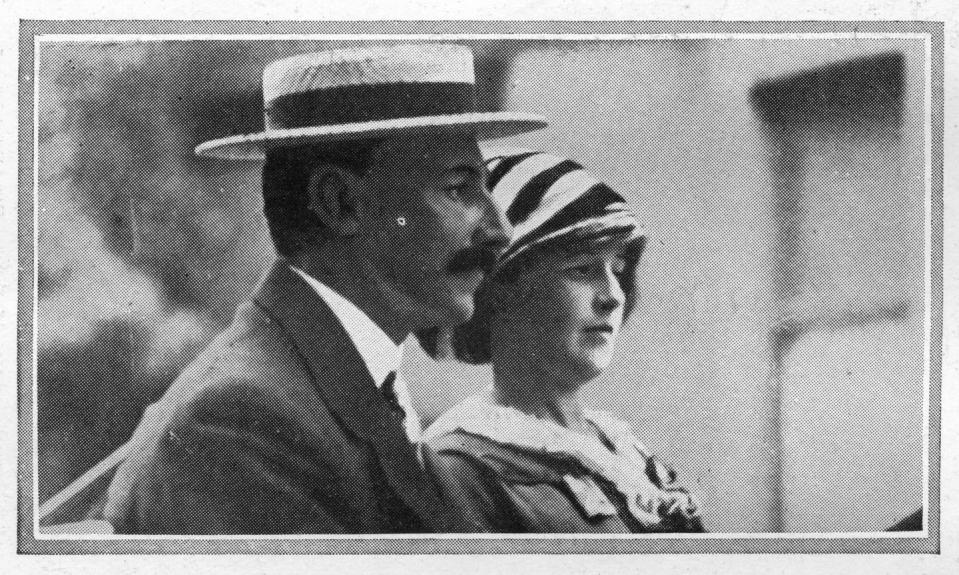

Down in their deluxe parlor suite on C Deck, Colonel John Jacob Astor IV, one of the wealthiest men in America, and his new young bride Madeline were getting ready for bed when Mrs. Astor noticed a rumbling and commented that it might be a mishap in the kitchen. Then, curiously, a framed picture on the bed table tipped over, breaking the glass, but neither she nor the colonel gave it much thought. Wintering with friends in Egypt had been a delight; Madeleine was now pregnant; their main reason for leaving the States had been to allow the scandal of his nasty divorce and subsequent remarriage to settle down, and they had every reason to believe that they beautiful Mrs. Astor would finally be accepted in New York society.

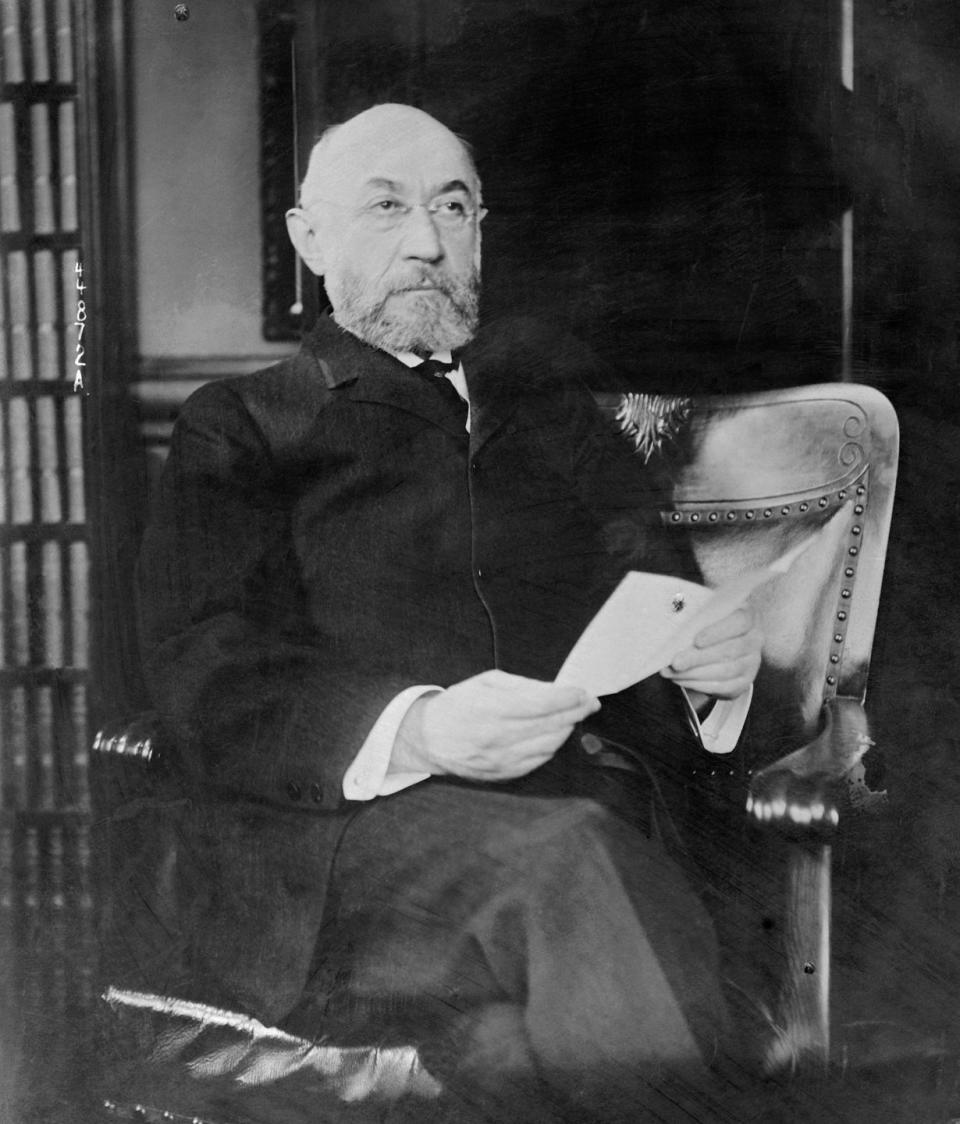

Directly across the ship in C 55, old Isidor Straus, who had made a fortune in commerce and banking before building up the great Macy’s department store and heading off to Congress, was reading Archibald Gracie’s new book about a later campaign of the Civil War, The Truth About Chickamauga. Farther down the corridor, Henry B. Harris, probably New York’s most important theater mogul, was playing double canfield with his wife in their sitting room. In C 80-82, Eleanor Widener, Harry’s mother, had just tucked two strands of 11-millimeter pearls worth $1 million in her jewel case since it was too late for the manservant to return them to the purser’s safe. And still farther back, in C 104, Major Arthur Godfrey Peuchen, a prosperous chemicals manufacturer, was certain a heavy wave had struck the ship as he rummaged through $200,000 in bonds and $100,000 in preferred stock he kept in a tin box. To Mrs. Walter B. Stephenson, the bump was more like the first mild jolt she remembered in the San Francisco earthquake—though certainly not as bad.

One deck above, in a three-room complex with private promenade priced at £512 (about $25,600 in today’s currency), Philadelphia banking millionairess Charlotte Cardeza, traveling with her maid, valet, 14 trunks, 4 suitcases and 3 crates of minor luggage, noticed the shudder and asked her son Thomas to step outside and take a look. In Suite B 84, America’s mining and smelting king, Benjamin Guggenheim, was sleeping soundly, but his manservant next-door rang the night steward to inquire if something was amiss. Still another prominent Philadelphian, young Jack Thayer, was just buttoning his silk pajamas when he heard a commotion in the corridor, threw on an overcoat and called to his famous father, second vice-president on the Pennsylvania Railroad, who was in the adjoining cabin, that he was “going out to see the fun.”

Further down the starboard side, Emily Ryerson, wife of steel tycoon Arthur L. Ryerson Jr., mistress of family homes in Chicago, Haverford, Pennsylvania, and Cooperstown, New York, and mother of a beloved son whose recent accidental death in an automobile accident in the States had forced her and her husband to book passage on the first available liner, was trying to get warm under the satin comforter when the iceberg slid noiselessly past the suite’s windows. A few moments later, she noticed that the engines had stopped. Not wanting to waken her grief-stricken husband, she slipped quietly out of bed and called the steward. “Is there any trouble, Bishop?” she asked. “There is talk of an iceberg, Ma’am, and they’ve stopped so as not to run into it.” Hearing the mumble of conversation from next-door, Margaret (Molly) Brown, eccentric and partly estranged wife of Denver mining man, J.J. Brown, came out still dressed in the black velvet dress and black-and-white silk lapels that she’d worn at dinner. “What’s going on around here?” she demanded.

On the lower decks, Second- and Third-Class passengers, some crammed four to a cabin not much larger than the Astors’ bathroom, had more reason to be alarmed than the grandees up top. One passenger in steerage jumped out of his bunk to find out what was causing the commotion outside his cabin. When he looked down, he saw water seeping under the door.

Meanwhile, in the Jacobean First-Class dining saloon, now abandoned save for four off-duty stewards, the silver already set for breakfast the next morning began to rattle ominously, while in the galley, where the bakers were preparing thousands of rolls for the following day, a large pan toppled off the top of an oven, scattering rolls about the floor. A First-Class steward, now off-duty and wandering about down E Deck, was surprised to be confronted by an irate passenger who threw down a hunk of ice and shouted, “Will you believe it now?”

Up in A 36, the man who built the Titanic, Thomas Andrews, managing director of Harland and Wolff Shipyard, was still laboring over blueprints of the liner when a message arrived that he was needed on the bridge immediately. It was midnight, just 20 minutes after the collision, as the ship’s stunned builder and its captain gathered in the chart room where Andrews, pencil in hand, quietly and slowly explained that the unimaginable had indeed occurred: the “unsinkable” liner could float with any 2 of her 16 watertight compartments flooded; she could even float with any 3 of her first 5 compartments gone; she could even float with all of her first 4 compartments out; but there was no way she could survive with all first 5 compartments flooded. And they were indeed flooded.

“So, what are you saying, Andrews?” Captain Smith asked, still holding out hope for a miracle.

“What I’m saying, Sir, is that she’s going to founder. It’s a mathematical certainty.”

The veteran captain stood motionless, staring intently at the diagram. Then he looked up at Andrews, his eyes glazed. “How long do we have?”

“One, maybe two hours—not much more.”

At 12:05, the captain ordered the lifeboats to be uncovered, the passengers mustered and the usual distress signal plus the new and more urgent signal sent from the wireless room. “CDQ—SOS from MGY,” the wireless operator taped out into the cold Atlantic night. (It was, in fact, an ocean liner’s first use of the SOS signal.) “We have struck iceberg. Sinking fast. Come to our assistance.” Back on the bridge the officers were forced to face the most horrible of truths: there were 2,207 passengers and crew on board. The most the 16 lifeboats and four collapsibles could carry was 1,178.

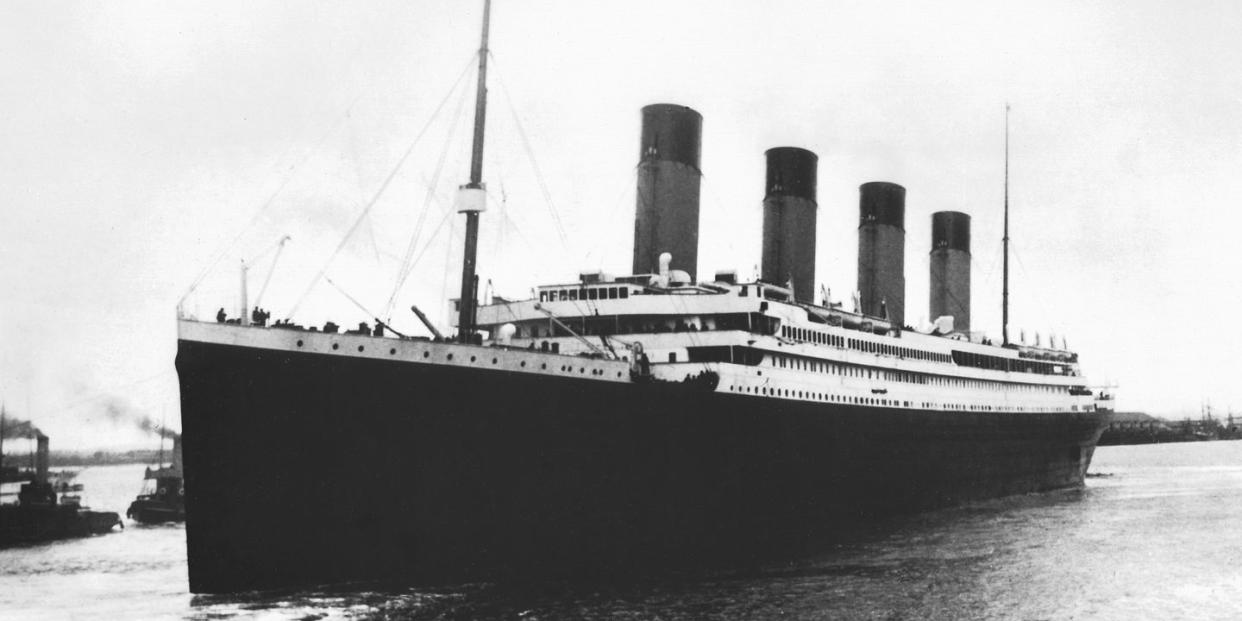

While many of the passengers remained uncertain of the extent of the damage, the seasoned mariners and engineers among them soon realized that Titanic was going down. Hundreds of lives would be lost, and the world’s most splendid liner, indeed the most perfect ship ever conceived by man, would not complete her maiden voyage. Nobody who ever saw Titanic failed to be overwhelmed by her stupendous size, her beauty and poise, her regal appointments and her vast power. Following the steady trend to produce ever larger, swifter and more luxurious liners that would appeal primarily to a growing affluent class of passenger (mostly wealthy Americans), the White Star Line had succeeded in creating two ships, Titanic and Olympic, that boasted the ultimate not only in comfort and amenities but in shipbuilding technology. The Olympic already had made headlines worldwide after her maiden voyage, but Titanic, because she was slightly larger than her sister ship and much more elaborate, promised even more splendor, more glory, more drama. There would be drama this night indeed.

To the moneyed American elite in 1912, nothing was more exciting and prestigious than this maiden voyage. Titanic, after all, had been proclaimed the greatest ship ever to cross the Atlantic. The passengers had booked their cabins months in advance, and the list of prominent names was a Who’s Who of the American aristocracy. Astors, Strauses, Guggenheims, Wideners, Thayers, Roeblings, Ryersons, Browns, Dodges, Carters, Harpers, Cardezas—all had boarded with their valets and maids, their chauffeurs and secretaries and dogs; some with 20 trunks of Paris frocks and evening dresses, Savile Row dinner suits and piqué waistcoats, and mink-lined great-coats; others with priceless jewels, personalized bed linens, gold garters and silk hats. (Just about the only blue bloods missing were J. Pierpont Morgan, George V. Vanderbilt and Henry Clay Frick, each of whom had to cancel at the last minute for one reason or another.) Unlike the less fortunate in the ship’s two lower classes, these exponents of the Gilded Age were accustomed to and expected the best in accommodations, service, cuisine and overall creature comforts; and every aspect of Titanic had been designed to satisfy all their demands—except, that is, for an adequate number of lifeboats.

The truth was that Titanic, like a number of other larger vessels of the time, was sailing under British Board of Trade safety regulations that were sorely out of date. There was, for example, the 1894 decree that simply required any ship over 10,000 tons to carry 16 lifeboats of a stated total capacity, plus rafts or floats. Titanic was all of 46,328 tons, legally certified to transport more than 3,500 people. Yet she was required to carry lifeboats for no more than one-third that number.

As the passengers mustered on deck in the bitter Atlantic cold, they had no way of knowing all this. According to most eyewitness accounts, there was virtually no panic, no rushing or pushing, no hysterical screaming as the distress rockets flashed overhead. At one point, Captain Smith shouted, “Women and children first!” through his megaphone, and two officers carried out his orders while allowing the occasional male to board in order to man the lifeboats.

“It was all very calm, almost quiet,” recalls 88-year-old Winnie Von Tongerloo, sitting comfortably in her home in Warren, Michigan. “The people were dressed ever way imaginable. Some in pajamas, some in beautiful fur coats. There were a few gentlemen still in formal attire. But it was so cold, and I was so frightened by the life jacket—terrified I might have to jump into that black water.” Von Tongerloo was 8 years old at the time.

At her home in Santa Barbara, the late Ruth Becker Blanchard remembered a steward opening the door to her cabin and directing her mother to bring the children up to the Boat Deck. Did they have time to dress? Her mother asked the steward. “No, Madam, you have time for nothing!”

Just four days before, Mrs. Isidor Straus had written a letter aboard Titanic that is now owned by her great-grandson Ken Straus: “But what a ship! It’s so huge and so magnificently appointed.” As the ship began to list Ida almost entered lifeboat number 8, but then changed her mind and rejoined her husband. “I will not be separated from my husband,” she said softly. “As we have lived, so we will die. Together.” After wrapping Mrs. Straus’ fur coat around their maid Ellen Bird and seeing her into the lifeboat, the old couple sat for a bit in the deck chairs, watching the other passengers. Then, around 12:50, they retired to their stateroom.

The ship was listing badly now, sinking slowly by the bow, and loading the boats became more difficult and dangerous. One by one, the ladies were handed by the gentlemen into number 4. Eleanor Widener, wearing her two stands of precious pearls, hesitated as her husband George placed on her finger his emerald ring. Across the deck, John Jacob Astor asked a crew member if he could join his wife since she was “in delicate condition.” Refused, he kissed Madeleine good-bye and stepped back, joining George Widener, his son Harry and John Thayer. Just then August Weikman, the ship’s barber, approached the colonel and asked if he minded shaking hands.

“With pleasure,” responded Astor, stepping up and pumping the barber’s hand. In his pocked that night were $4,250, and a gold watch, which were returned to the family after Astor’s body was found among those recovered a few days after the accident. Today the watch belongs to Brooke Astor, widow of Astor’s son Vincent, and Mrs. Widener’s emerald ring is on the finger of her grandson Fitz Eugene Dixon Jr., as he sits thinking about her, his grandfather and that awful night 80 years ago.

At 1:25 A.M., Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall and Quartermaster George Rowe observed another vessel no more than five or six miles away, and they tried repeatedly to signal with the Morse lamp, only to watch as the ship vanished into the night.

As the boats filled with their wives and sweethearts pulled off into the night, the men aboard Titanic reacted in their own ways. Benjamin Guggenheim and his valet went down to the B Deck, removed their heavy clothing and uncomfortable life belts, and returned in full evening dress. “We’ve dressed up in our best,” Guggenheim told a steward. “And we are prepared to go down like gentlemen.”

Farther up the deck, bandmaster Wallace Hartley tapped out the beat of ragtime, but as the water continued to inexorable climb, he directed the orchestra to play “Nearer, My God, to Thee,” the hymn he’d once said he would select for his funeral.

It was 2 A.M. Archie Butt and Clarence Moore headed back to their regular card table in the smoking room, where they were joined by Arthur Ryerson and the painter Francis Millet for a final hand together.

At 2:05, Captain Smith released the hardworking wireless operators in the Marconi shack from their duty. “It’s every man for himself,” he told several crew members, and returned to the wheelhouse. Underlined in red on the White Star notice posted on one wall were the phrases “safety outweighing every other consideration” and “over-confidence, a most fruitful source of accident.” The captain was alone when the bridge plunged into the sea.

When the last collapsible boat (boat D) was readied for launch, young Edwinna MacKenzie chose not to enter, declaring, “This is such a glamorous way to die.” Decades later at her home in Hermosa Beach, California, she would recall how another passenger had thrust an unidentified baby into her arms. “Save the child; save yourself,” he told her. She got into the raft.

At 2:15, her lights still burning brightly, Titanic’s stern rose higher and higher against the starlit sky, and the first massive black-and-bluff-colored smokestack broke away. There began a long, thunderous roar as her innards burst their holds and hurtled toward the sunken bow: 29 boilers, 100 barrels of flour, Mrs. Cardeza’s 14 drunks and Mrs. Widener’s Paris trousseau, 5 grand pianos, a bejeweled copy of The Rubayat of Omar Khayyam, Billy Carter’s new Renault, potted palms and trellises, tons of coal, 15,000 bottles of ale and stout. And the bicycle an 84-year-old survivor, Louise Pope, still thinks about …

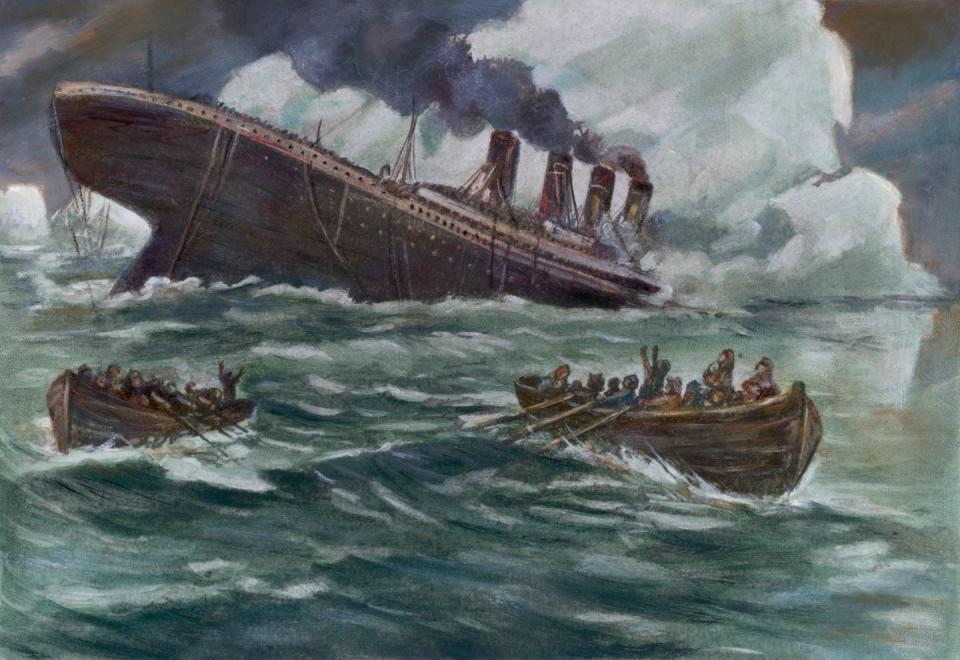

For almost half a minute, Titanic assumed a near-perpendicular silhouette against the horizon: then, settling back with her lights now out, the regal ship that God Himself could not sink began slowly, smoothly and ever so steadily her two-and-a-half-mile dive to the bottom.

In all, 1, 517 passengers and crew perished, while 690 survived to bear witness to the horror of a sea strewn with masses of wreckage and hundreds of struggling men, women and children freezing to death in the 28-degree water. “The agonizing cries of death from over a thousand throats,” was the way Archibald Gracie remembered it. “The wails and groans of the suffering, the shrieks of the terror-stricken, the awful gaspings for breath of those in the last throes of drowning—none of us will ever forget to our dying day.”

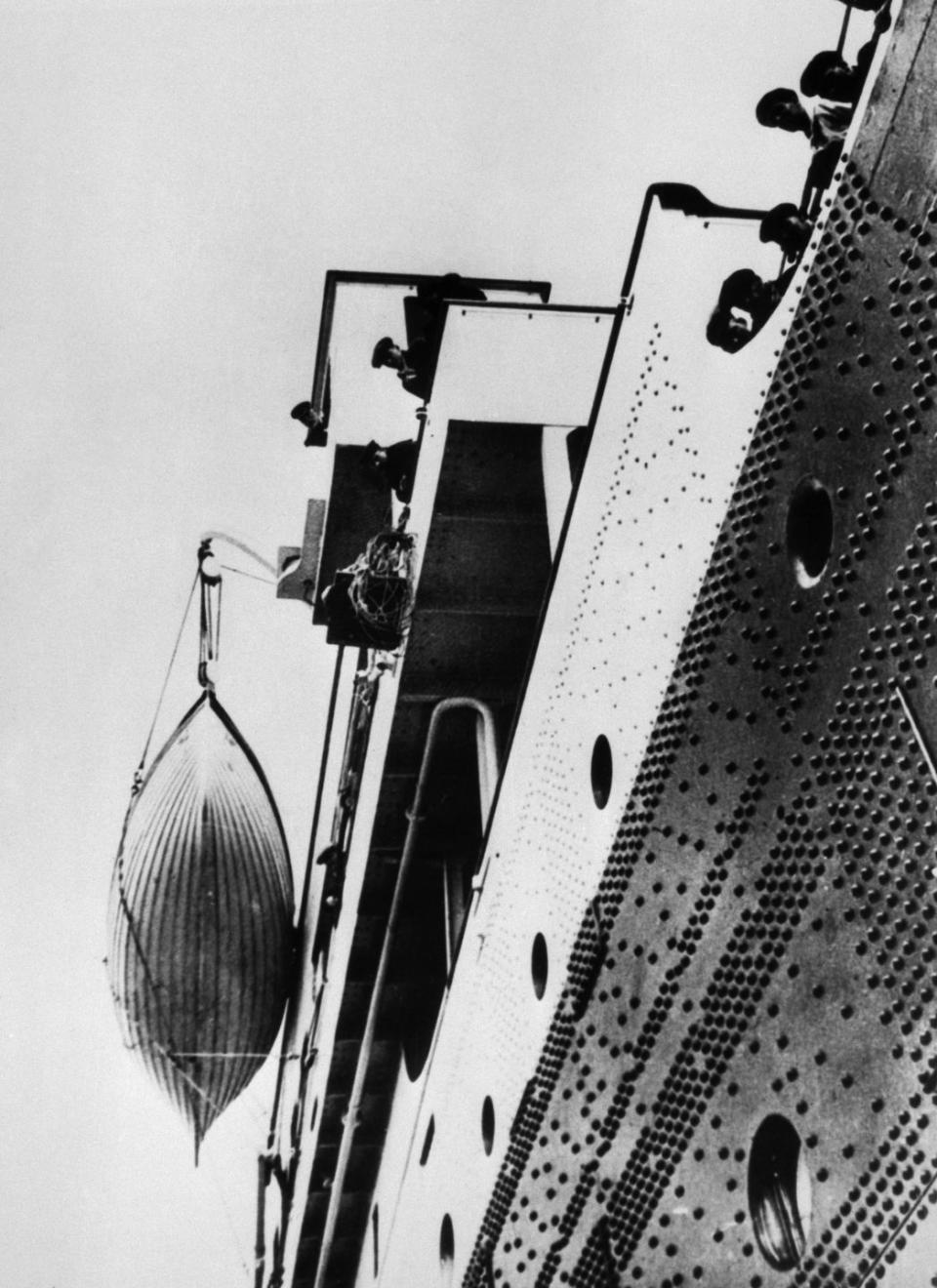

At 4:10, the ship Carpathia, having raced through the ice field on hearing the SOS, finally appeared in the mist and began the task of taking on board survivors: the young and the old, the rich and p0or, the famous and the unknown, the clothed and the half-frozen. Slowly, they were hoisted aboard in slings or chairs, or helped to climb rope ladders; some children were hauled up in canvas bags; and warm clothing and food were distributed. For a long while, women searched desperately for their husbands, and children cried out for their fathers or both parents. Then, when the ship turned, plotting a course for New York, most gave up hope.

According to one apocryphal story, a woman attendant tried to force hot coffee on a woman survivor curled up in a blanket, reminder her that “this was God’s will.” “No coffee,” murmured the woman, “and no God. God went down with the Titanic.”

For eight decades, this worst of all peacetime maritime disasters on the North Atlantic has fascinated, intrigued and horrified. Books have been devoted to the saga, major films and TV specials have been produced and veritable cults have been established. In 1963, a young jeweler in Indian Orchard, Massachusetts, named Ed Kamuda founded the Titanic Enthusiasts of America, later renamed the Titanic Historical Society (T.H.S.), an organization created to “perpetuate and investigate the memory and history of the Titanic, Olympic and Britannic.”

Today, the society not only includes almost 5,000 members worldwide but publishes quarterly The Titanic Commutator. Housed behind Kamuda’s jewelry shop in Indian Orchard are the T.H.S. archives and library at the official Titanic museum, while not far away, at the Marine Museum at Fall River, is another collection (including Mrs. Astor’s life jacket and deck chair); the two comprise the largest collection of pre-discovery Titanic artifacts in the world.

For years, concerted efforts to locate Titanic proved futile. Then, as the world watched on TV in 1985, Dr. Robert Ballard and teams of American and French scientists revealed the first glimpses of the lost liner, in two pieces, sitting upright in her ocean grave. Some enthusiasts were ecstatic over the discovery; others were appalled.

Although emotions remain radically mixed, discovery of Titanic (which, so far, has provided little of monumental value or significance) has served only to heighten public interest and debate as the various artifacts retrieved are cleaned in Paris for display and recovered evidence either sheds new light on the disaster or adds more mystery to the mass of apocryphal information and guesswork that still surrounds it. Serious collectors around the world flock to auction houses and private sales for any object even remotely connected with the legacy, paying premium prices for Titanic letters, postcards, menus, pieces of carpeting, survivor souvenirs and other memorabilia.

Someone like T.H.S. historian Don Lynch, the author Titanic: An Illustrated History (to be published by Hyperion Press in September), whose encyclopedic knowledge of Titanic’s passengers is daunting, devotes virtually his entire existence to researching those who were on board and their descendants. Ship illustrator Ken Marschall, whose paintings and illustrations of Titanic have graced numerous books and the cover of Time, now knows the configuration of every porthole, the various types of wood on board, every light fixture and panel of stained glass. His personal collection of artifacts includes ships’ wireless forms dated April 15, 1912, and Titanic china never put on board. And when George Behe is not operating his family’s exterminating business in Michigan, he is combing catalogs for priceless original deck plans, among other objects. As for myself, I am one (among thousands) whose involvement with Titanic is as inexplicably passionate today as when I sat around a campfire as a child mesmerized by a song about the ship — no doubt the best explanation of why my most exciting memories have always revolved around crossings in Queen Mary, Ile de France, Michelangelo, S.S. France and, indeed, my beloved Queen Elizabeth 2.

By last count, there are 18 living survivors of the Titanic, including one who debarked at Cherbourg and one who debarked at Queenstown; in all, there are eight in the U.S. The oldest is 103 and the others are in their 80s and 90s. The T.H.S. has managed to communicate with them all; other buffs have established close and lasting relationships. I’ve been privileged to know only five, but to talk with these Edwardian ghosts and hear their firsthand testimony is to relive the legend, to feel part of the link that connects us with the great tragedy of 80 years ago. It does seem to me that none of these survivors speaks fully outright about his or her experience. Perhaps it’s because they were just children at the time. But I sense that there is more, that even after all these years, the memories are too painful. Eva Hart, for instance, tells how her mother sat vigil in her stateroom every night because she had had a premonition of disaster, but her only clear recollection of being in lifeboat 14 is that she was terrified when an officer fired a pistol to reestablish order. Winifred Von Tongerloo (who treasures the small souvenir White Star flag found in her mother’s pocket after the rescue) remembers the smell of fresh paint in the stateroom and the oversized shoes she was given aboard Carpathia, but only when pressed does she mention the mammoth smokestack breaking away at the end, the “happy” music played on Boat Deck as the liner was sinking, the voices of victims in the water, and the canvas bag that lifted her from lifeboat 11.

Louise Pope (who subsequent to Titanic, also survived two world wars, the Great Depression, tuberculosis and breast cancer) has her shoes and blanket from the lifeboat, and she sometimes wonders what happened to her new bicycle that was on board. Otherwise, her memory is blank, even after sessions of intense hypnosis. Although Eileen Schefer crossed only from Southampton to Cherbourg, she recalls vividly the red carpeting on the grand staircase, the waltzes played in the stately Palm Court, the gymnasium and “swimming bath,” the exquisite flowers, silver and glassware in the grandiose First-Class dining saloon, and her mother’s shock on the street in Paris when she saw the bulletin that read, “Blesse a Mort, le Roi des Paquebots.” After having to pay £1,000 at auction 75 years after the sinking, Mrs. Schefer also once again owns the letter she wrote to her governess from aboard Titanic, which was mailed from Queenstown, Ireland, the ship’s last pre-crossing stop.

Of equal interest to me have been the descendants of the victims and survivors, many of whom in America are located in and around Philadelphia. Fitz Eugene Dixon Jr., grandson of George D. Widener, twists his emerald ring as he questions to recent exploration of Titanic: “Why can’t they leave the ship alone? There was just too much sorrow for too many people.”

Mrs. John B. Thayer, daughter-in-law of survivor Jack Thayer, not only has Titanic material collected by her late husband but has an entire room devoted to liners and the sea. Arthur P. Dodge, whose father, grandfather and grandmother survived, has already passed down to his son a rare First-Class menu, and he doesn’t hesitate to disclose how his grandfather, Dr. Washington Dodge was falsely accused of stepping disingenuously into a lifeboat. Spencer V. Silverthorne III remembers his grandfather well, and his family still guards the telegram sent from Carpathia verifying the retailer’s survival. He also recalls how his grandfather always had to be coaxed to talk about the tragedy, suffering, perhaps, from the same strong feeling of guilt that seemed to plague so many male survivors (Jack Thayer, Dr. Washington Dodger and lookout Frederick Fleet committed suicide years later). “He’d tell about rushing on deck from the smoking room to see the iceberg, how his frozen fingers had to be peeled from the oars after he’d been rowing, and how he gave up his coats so a baby could be rapped; but he never really wanted to discuss the Titanic.” And what does the saga symbolize to young Silverthorne himself? “That we learned nothing about overconfidence and losing respect to the forces of nature,” he says. “Did you watch Apollo 13 on TV?”

Framed on the wall of Macy’s heir Ken Straus’ elegant New York apartment is not only his heroic great-grandmother’s letter but also a very jolly one written aboard the Amerika by his grandmother, dated April 17, 1912. In part it ready: “Two days ago the captain knocked on our cabin door at 7 o’clock in the morning to tell us to come on deck to see two big icebergs.” Do you realize what that means!” exclaims Ken. “It means that my grandfather Jesse crossing in the opposite direction, still did not know that his parents had perished on the Titanic two days before and could have been looking at the very berg that sank her!”

Jackie Astor, whose father, Jack, was born to Madeleine Astor after her rescue and who now lives in Florida, shares little of Straus’ interest and enthusiasm when it comes to her famous family’s Titanic history. “My father has not mentioned the Titanic in years, and I assure you he wouldn’t discuss it now. It was all so sad and tragic for his mother and him and the whole family. You know, his parents were truly very much in love, and I think the memory of it all has affected his whole life. Why can’t people just forget the Titanic?”

Exactly who and what were to blame for the disaster? For decades, accusations have been directed at every source imaginable: at Captain Smith for ignoring ice warnings and racing through the sea at 22 ½ knots; at insufficient lookouts; at the first officer for reversing the engines and thereby depriving the ship of adequate power to skirt the iceberg; at the White Star Line’s (undeclared) insistence that the vessel make schedule at all costs; at the abysmal number of lifeboats and a crew inept of handling the boats; at the failure of the “mystery ship” that Boxhall and Rowe noticed in the distance (thought to have been the Californian) to recognize that another vessel might be in grave trouble; and even at the overweening pride and arrogance exuded by officers with a blind faith in technology and a bunch of rich, complacent Americans who honestly believed that if the tickets cost enough a ship could be unsinkable.

Undeniably, serious mistakes were made, the worst being the number of lifeboats and the careless way they were loaded. But it’s likely we’ll never know the whole truth — despite any future expeditions to further explore the wreck.

I believe that this worst of all North Atlantic ship disasters (followed so quickly by the ravages of World War I) marked the end not only of a very fragile social system in both Britain and America but of a deceptive trust and confidence in material progress that once seemed to guarantee an orderly, steady and highly civilized rate of progress. We were so sure of ourselves, so full of our vanity, so convinced on our accomplishments and infallible abilities. In some ways, what happened in April of 1912 was like what happened in October 1987, when America’s invincible market crashed and her economic interest became apparent.

Gone with Titanic was an inimitable cast of heroes and heroines, snobs and fools, rouges, and miscreants, all of whom comprised a laboratory of human nature the likes of which even Hollywood would find difficult to portray. Plutocrats like Astor, Straus and Widener were known as robber barons, yet what fascinates us most about these gold-plated gentlemen is not the millions they pocketed but their sense of courtesy, good manners, style and, indeed, self-sacrifice. Ivan Obolensky, grandson of J.J. Astor by his first wife, makes an important point when he says that “these guys always put back when they took out,” a creed that assumes even greater implications today when comparisons are made with a Donald Trump, Leona Helmsley, Oscar Wyatt or Ivan Boesky.

By the 1930s, liners would nearly double Titanic’s size while still providing luxury and glamour as the Golden Age of ocean travel developed; yet neither Mauretania nor the Normandie nor the majestic Queen Mary would ever see a J.J. Astor making small talk with a barber while waving good-bye to his wife for the last time, or a Thomas Andrews standing proudly and solemnly in the smoking room as the ship sank steadily into the sea, or a Wallace Hartley directing a doomed orchestra to play “Nearer, My God, to Thee,” or a Molly Brown in a lifeboat brandishing a pearl-handled Colt revolver retrieved from her sable muff. This was drama on a grand scale. This was the essence of tragedy.

I am standing on the bridge of Queen Elizabeth 2 in early evening. This is my 38th-crossing in this last of the magnificent transatlantic luxury liners. I’ve been invited here to the bridge by Captain Ronald Warwick for a friendly chat before cocktails and dinner. After two days of battling a force-10 gale, we are now in calm weather, plowing through the water south of Newfoundland at 28 ½ knots, trying to make up time. Outside, the weather is frigid, the black sea smooth as marble and the sky speckled with millions of tiny stars.

As the captain and I talk, I notice that the officer of the watch periodically looks up from his radar and computer boards, grabs a pair of binoculars, and peers out over the bow.

“Do you mind if I ask you a crazy question?” I say to the captain. “Do you ever think about the Titanic on this run?”

He sips his coffee a moment. “Well,” he mutters, almost embarrassed, “I don’t suppose there’s a master on the North Atlantic who doesn’t think about that.” He hesitates, glances over at the first officer, who is again looking intently through the glasses, then gazes out to sea. “I’m sure there’s nothing to it … but, in fact, just this afternoon we got a report from another ship in the vicinity. She thought she saw a large berg.”

You Might Also Like