Why the Director of Murder on Middle Beach Turned the Camera on His Family

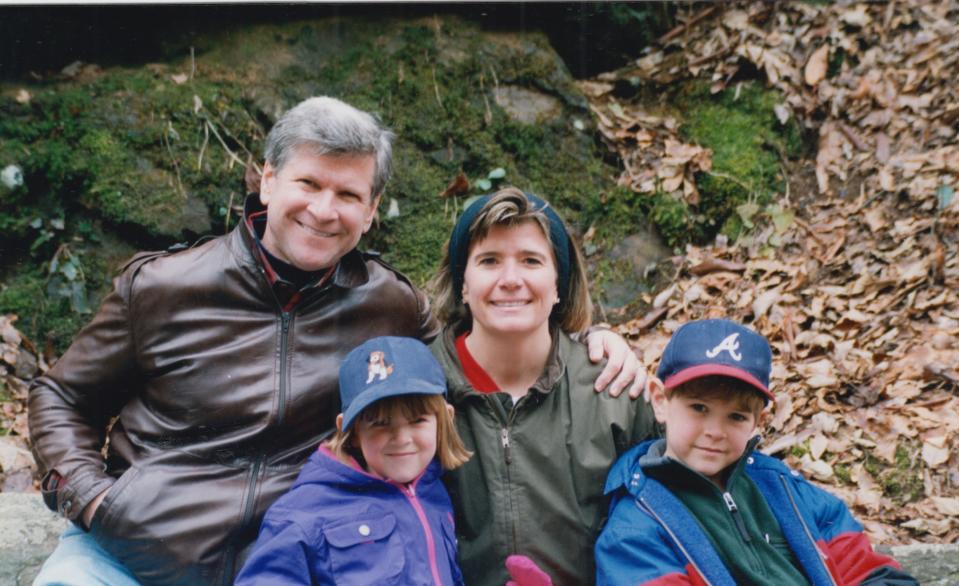

For 10 years, Madison Hamburg has been leading what he calls a “double life.” He hadn’t told most people he knew that his mother Barbara Beach Hamburg was found murdered in the backyard of her Madison, Connecticut home back in 2010. He also hadn’t told most people that he’d spent much of his time since then working on an extensive, revealing documentary about his family in the aftermath of her death.

“There's shame attached to what happened to me. I wanted to avoid pity, but mainly I wanted to avoid assumptions,” Hamburg tells me in a Zoom call from his Brooklyn apartment, a few days before his docuseries, Murder on Middle Beach, premieres on HBO. “Leading up to this release, there's a lot of relief because I feel whole again.”

Hamburg, now 29, started the documentary as a class project while he was a student at Savannah College of Art and Design. It was 2013, and he was newly recovering from an opiate addiction and freshly grieving his mother. “I was a drug addict, and I ran from accepting a world without her,” he says. “I chose to get sober because I was going to die. I decided, if I was going to accept a world without my mom, I was going to make the absolute most of it that I could.”

He quickly amassed more new and preexisting footage than he could handle, and didn’t even complete the assignment. (His professor gave him an A, and insisted Hamburg see the project all the way through one day.)

Originally, Hamburg embarked on this endeavor to preserve his mother's memory and to get to know her as an adult. But by 2016, it dawned on him that his film could be significant in another way: as a tool to reopen what had become a frustrating cold case. Barbara’s murder had come as a seismic shock to their idyllic shoreline town—a mother stabbed and bludgeoned to death, whose body was discovered by her sister and teenage daughter, while her ex-husband was a person of interest—but had languished unsolved for years.

“I started to realize that we were gathering information that the police potentially didn't have,” Hamburg says. “That's when I felt, whether or not I could solve the case, there was a potential to exonerate people, to dispel the distrust. It was also a moment where I felt the investigation would be eventually reactivated by the act of doing this.”

It was also around this time that producers got involved to shepherd the project to its next stage. An uncle of Hamburg’s reconnected with an old friend, the producer Ron Nyswaner, best known for writing the screenplay for Philadelphia. Hamburg was in another production company’s office, about to sign a contract, when Nyswaner rang him. “He called me and said, ‘I'm flying you out to LA. [Director] Jonathan Demme changed my life from one phone call, and I'm going to try to do the same for you,’” Hamburg recalls. Together with producer and longtime collaborator Neda Armian (Rachel Getting Married), they pitched it around, with Hamburg using vacation days from his day job to secretly take meetings. Hamburg remembers his then-boss at the design studio he worked at asking him, “what are you doing on your PTO time where you're coming back from your vacation more tired than when you left?”

Armian recalls the first time she heard Hamburg’s story over the phone. “I rarely do this because I find it annoying when you're on a call, but I kept texting [Ron] things like OMG,” she tells me. “I don't speak like that, I don't text like that.”

“It's a really good story. I say that with the awareness that to call somebody's tragedy a good story is a little callous,” Nyswaner says. “We'll learn something and we'll say ‘Oh my god that's amazing.’ And then we'll go, ‘I'm sorry actually. I now remember we're talking about your mother's death. It's not amazing, it's actually heartbreaking.’”

This gets to an inherent tension of true crime, which is made even more explicit when the filmmaker is as close to the subject as Hamburg is. What is the line between tragedy and entertainment? How complicit is the audience in consuming someone else’s pain? Murder on Middle Beach is premiering at a time when the genre is both more popular than it’s ever been—and more scrutinized. There’s been increased critique of the sorts of victims it focuses on and those it ignores, for its macabre obsession with grim details, for its inherently exploitative nature. Hamburg himself is not a fan. “I think victims get lost,” he says. “I think the fetishization and focus on killers and the crime and brutality of it is really harmful to the families that are left in the wake of these things.”

He’s adamant that his docuseries subverts the traditional trappings of the genre, and in many ways it does. Murder on Middle Beach is infused with humanity, and is a deeply personal, heartfelt journey of a son looking for answers. Hamburg also frequently breaks the fourth wall as he grapples with the ethics of what he’s doing. “While my intentions were good, it could be destructive for my life and my family's life. It has the potential for a lot of destruction,” he says. “Naming that was really important for me.”

The story is told through interviews with his family members, as they build a portrait of who Barbara was: a loving mother, a strained divorcée, a recovering alcoholic who found community and purpose in Alcoholics Anonymous. (Her sober anniversary is Valentine’s Day, Hamburg tells me, and he still goes to meetings every year to pick up her chip.)

But it never completely escapes the true crime label. The story unfolds in captivating layers cloaked in suspense, like when it’s revealed that Barbara was a prominent member of a pyramid scheme known as “gifting tables” that, after her death, was prosecuted in the state of Connecticut. And there is a strong mystery undercurrent, as he unflinchingly asks many of his family members if they killed his mother on camera.

How was Hamburg able to convince his family to take part in this? “At first, I don't think anyone thought that this was going to be on a national stage,” he says. “I think they all wanted me to understand who my mom was and to fill in some gaps that they were protecting me from to have some tonality to her death and hopefully some closure.”

There are two parties in the docuseries who were surreptitiously taped without their knowledge. The first is the Madison, Connecticut police. The other is his father, Jeffrey Hamburg, who barely had a relationship with his son in the years following the divorce. (In addition to being a person of interest, Jeffery was accused of not paying child support and depleting his children’s trust funds.) I ask how he weighed the ethics of doing so in both cases.

“The police were really easy for me,” he says without pause. “It felt like it was my first amendment right to have a record of that conversation if it were ever to be used against me. So that was never an issue for me. Plus, I was originally only doing it for notes because I didn't have a pen and paper at those meetings.” The police had also been resisting contact with him throughout the process. “I don't know why they stonewalled me so much. It was really frustrating as a family member, especially because I was offering them pieces of information,” he says. “That really frustrated me, to not give me the time of day for weeks on end. But I hope that this series is an opportunity ... to develop a different kind of relationship with the board.”

Hamburg wrestled more with taping his father, who was unaware that the documentary was happening. Initially, he didn’t even include the audio of his father’s side of their conversations, bu says he found that to be more ethically dubious. “One of my dad's biggest complaints about the way that the media portrayed the story was that his side of the story was unable to be heard,” Hamburg explains. “He felt like he was being pointed at as a person of interest, and that they got tunnel vision and it ruined his life. And if he didn't have anything to do with my mom's death, that's really traumatic. I wanted my dad to have a voice in the film.”

The last time he spoke to his father was on camera. But he has hosted screenings for the rest of his family in advance, to prepare them before it went out into the world. “It’s been really tough. It's tough to see yourself on camera, it's tough to hear your voice in a recording if you're not used to it,” he says. “They’ve dealt with it really well with a lot of patience and we've had a lot of long conversations.”

“I think my mom, no matter what I did in my life, good or bad, would be proud of me. And I think that my family is sort of channeling that when they are watching,” Hamburg adds. “It's hard for me not to feel selfish and exploitative, opportunistic. Those are all my deepest fears of what this might come across as. But I don’t know. I'm okay with where we're at now.”

Originally Appeared on GQ