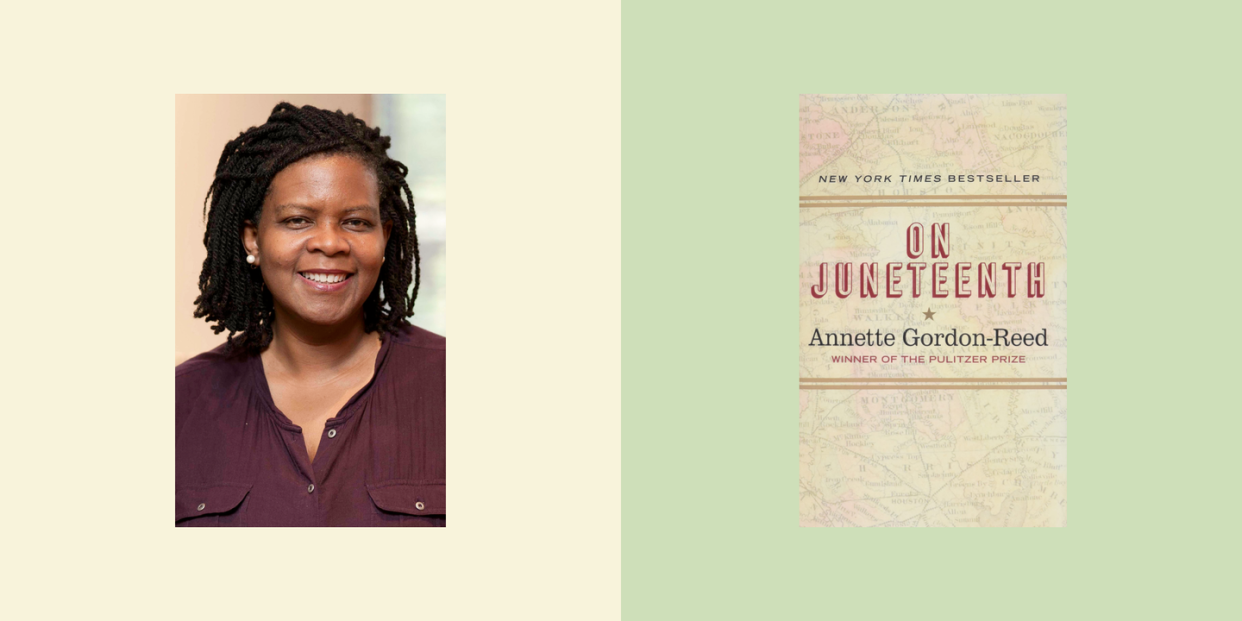

Why Celebrating Juneteenth Is Important, According to Annette Gordon-Reed

Intro

Your new book, On Juneteenth, is such a wonderful mélange of the personal and the historical. First of all, it seems like you love Texas, where you grew up, despite its very troubled record in terms of slavery, white supremacy, racism.

From my earliest days, it was drummed into me that we Texans inhabited a unique place that we were always supposed to claim, and of which we were always supposed to be proud. It is hard to meet a person from Texas who does not, at some point in the conversation, let you know, either with a drawl or without, that he or she is from the state.

But, the state has not historically been at all progressive in terms of racial politics.

It was a slave-based economy, and Anglo-Texans had been fighting for their “way of life” since the 1820s. They were confident that their alliance with other Southern states during the Civil War would solidify their position and enable them to remain a “slave society.” But two years after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation and two and a half months after Lincoln was assassinated, Major General Gordon Granger brought the news on June 19, 1865, that that effort had not succeeded.

And yet…

And yet abstract notions of places—of Texas—for me, at least, don’t capture why places are worthy of love. Texas is where my first family and connections were. It’s where I lived with my father, mother, and brothers. It’s where I rode back and forth between Conroe and Livingston to visit my grandparents, aunts, and cousins. It’s where my father drove me thirty-five miles to Huntsville, at my mother’s behest, for piano lessons with Mrs. Tull, who had been a professional classical pianist. In other words, Texas is where my mother’s boundless dreams for me took flight. About the difficulties of Texas: Love does not require taking an uncritical stance toward the object of one’s affection. In truth, it often requires the opposite.

And in the book, you write that where you grew up “shaped my thinking and actions in important ways.” Reading was a big piece of that, right? For example, you were a “Bluebird…”

In those days, people didn't care as much about children's self-esteem. So they divided us into groups: the good readers, the okay readers, and the not good readers. The good readers were Bluebirds. We had our own little circle and the books we read were a bit more advanced.

You were attending an all-white school because your parents thought that’s where you would be offered the best opportunities.

Yes, I was essentially integrating the school. I made it easy for them in the sense that my mother had prepared me. I was a very good student and loved reading and learning and so forth. The teachers were wonderful but they didn't have to take any extra effort with me at all, because I took to it very, very quickly and easily. I definitely wasn’t a problem child.

What is the first book you remember really having an impact on you?

A children’s book about Egypt and the pyramids awakened my interest in history. And then in the third grade I read a children’s biography of Thomas Jefferson, that he’d written the Declaration of Independence but was also a slaveholder. And then there were all these series that we had—on Martha and George Washington, on George Washington Carver, and, Frederick Douglass. Books like that really fascinated me.

So you were a historian even way back then! Yet in the book you write that slavery wasn’t something that was fully taught in school.

I remember one time a history teacher who was talking about George Washington said to the class, "Wouldn't it be great to live in those times?” And I said, "No, because if I lived in that time, I would be a slave." Teachers mostly didn’t want to acknowledge slavery, but there was also a discomfort about the topic among Black students, because you never knew what people were going to say, how we were going to be portrayed.

What’s an example?

There was a book narrated by a fictional enslaved boy who was supposed to be a companion to Thomas Jefferson. He was depicted as wanting to play all the time. He was mad at Jefferson, because young Tom Jefferson would want to be reading or doing some experiment, while the enslaved boy wanted to go fishing. And I knew even in fourth grade that there was a message in that. It wasn’t Isn't it terrible that this Black kid is not being taught to read, is not learning but instead he is made to seem trifling and ridiculous while Jefferson is smart, inventive, curious. As the only Black person in that class, I got the message.

What was the first book you read in which you saw yourself?

It was the first time I read James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son and No Name in the Street. I loved his voice. I can hear his voice. He was a gay Black man, and I'm a straight Black woman, but his sensibility spoke to me very, very clearly when I was an early teen. And his commentary is still so pertinent to many of the things we’re talking about now.

This past year has been an awakening for some, and also a grave disappointment—a reminder of how far we have to go. What’s your read on it, post the murder of George Floyd?

I think it was amazing to see protests and demonstrations erupt all over the country—around the world, post his killing. And it opened the conversation. I teach criminal procedure at Harvard Law School, and it's all about stop and frisk and police encounters with people, and so I’ve been talking about this stuff with my students for years. Yet I've never experienced a moment like this one, where the conversation about policing in America is on the minds of so many. That’s a hopeful thing. But then there’s the backlash, especially against voting rights. That concerted voter suppression is a serious threat to our future, and we’re not paying enough attention to it.

Can you say more about that?

Black and white people came out to protest, and also to vote, in record numbers, and the response to that has been “let's cut that off.” And some of the moves that have been made to limit voting have been really successful. I didn't expect a quick reform of policing in America; that's going to take time. But it’s not going to happen if people can’t vote. So this is a very treacherous period.

On this Juneteenth, how do you see your role as historian?

You can't have an accurate picture of history unless you have the multiple voices of the multiple people who helped to make it—yes, the famous people should continue to be known, as should those people they were nurtured and influenced by. Those more obscure people's stories—some of which have been hidden or erased—are interesting and important too, but we have to be able to get at them. We still have a long way to go on that front.

Your book On Juneteenth has a lot of great history in it, but it’s also a kind of ode to the family celebrations around the holiday that you had growing up in Texas, tamales and all. Why was Juneteenth important to your family?

Actually, I was really surprised, some years ago, to hear people outside of Texas talking about and celebrating Juneteenth. I confess I was initially annoyed. There was a twinge of possessiveness. But then I thought why should this irritate me? After all, it was a positive turn and should be saluted far and wide.

You write in the book that for some of your relatives, slavery was “just a blink of the eye away,” so Juneteenth was about celebrating the liberation of people they’d actually known—it wasn’t just a holiday, a day off.

My great-grandmother’s mother’s third husband, for example—she outlived three husbands—was enslaved until the end of the Civil War. Many were remembering family members who were lost. We children celebrated with the fireworks my grandfather bought—setting them off well into the night. And we had a feast: The traditional Juneteenth menu, in addition to the usual southern-style cuisine, included red “soda water,” as we called it, as we were normally not allowed to drink soda, and barbecued goat. As the years passed, another item was added to the menu: hot tamales. I remember sitting in the kitchen with my grandmother, her sister, and my mother for hours, preparing them—softening the corn husks in hot water, grinding the pork, beef, or chicken, and so on. It was so laborious. But it was time spent with people I loved, who are no longer with me.

How do you commemorate Juneteenth now?

I have not made tamales in many, many years. Now it’s more about recalling memories, looking at pictures, talking with my native New Yorker kids about it. I have a feeling I'm going to be celebrating it in a big way this year.

You Might Also Like