Why Alexey Brodovitch’s Work Still Matters in Art, Design, Fashion and Photography

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The bold work of Alexey Brodovitch, who died in 1971, will be on view at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia from March 3 through May 19.

Widely known for his 24-year reign as the art director of Harper’s Bazaar until 1958, his influence on his metier, as well as photography and graphic design, remains. Highlighting 100-plus works from public and private collections around the world, “Alexey Brodovitch: Astonish Me” will be set up as a series of vignettes. They will include photographs, prints, books, magazines and works on paper, including some from such key collaborators as Eve Arnold, Richard Avedon, Lillian Bassman, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Irving Penn.

More from WWD

What Happens When Actress Melissa McCarthy Discovers a Fashion Designer on National TV

Inside Sophie Krakoff's New Venture, Friends of the House Group

'Fashion Icons' Series Lines Up Stan Herman and Hal Rubenstein for Upcoming Talks

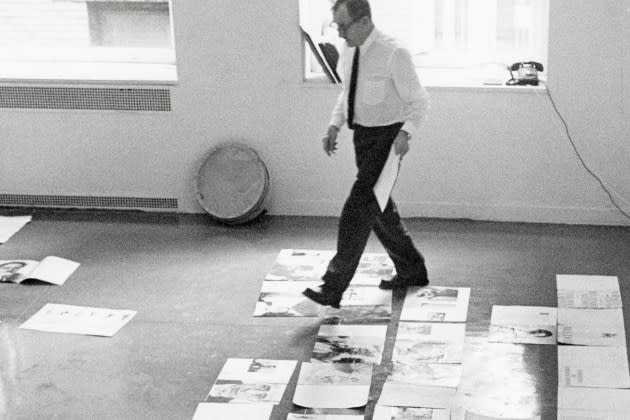

Brodovitch helped define the careers of such photographers as Hans Namuth, as well as abstract artists. The art director persuaded a reluctant Namuth to travel to East Hampton, N.Y., to capture Jackson Pollack at work on his studio’s floor. The end result raised the artist’s profile and created a better understanding of his work and technique.

The show’s curator Katy Wan first discovered Brodovitch’s reach in researching Garry Winogrand 11 years ago. “I didn’t understand how this figure seemed so pivotal in the careers of many other photographers and designers. He has been associated with a great number of other figures, who have inarguably been more recognized in their own rights. But he hadn’t been recognized for his own talents.”

As the title of the show suggests, the aim is that visitors will be surprised by the sheer diversity of his projects and those of his students — none of whom abided by one set style. The title also was inspired by Ballets Russes founder Sergei Diaghilev, who was in Paris in the ’20s along with Brodovitch. The French-speaking Diaghilev was known to tell his dancers “Etonnez-moi” — “Astonish me.” Brodovitch appropriated the phrase in his own teaching and his own design work across disciplines, Wan said.

Born in Russia to aristocratic parents, he was always artist-minded but was forced into military service during World War I and later joined the Russian Imperial Calvary to fight the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War. In 1920, he relocated with his wife Nina to Paris and a decade later moved to the U.S., settling in Philadelphia. There he established the Department of Advertising Design at the Museum School of Industrial Art, which is now part of the University of the Arts. Before Penn became a lion in photography, he was among Brodovitch’s students.

The art director’s sense of scale and strong silhouettes amplified the ethos of Harper’s Bazaar during his tenure, which was “to build a world of aspiration that subscribers in the U.S. and beyond could imagine they were in Paris at the runway shows,” Wan said.

Wan’s hope is that the physical experience of seeing the exhibition in person will show the ways that photographers make important decisions about not just the scale, but the printing techniques and what they choose to include and omit in their images. “Sometimes Brodovitch had a contentious relationship with his students. There were many he had an excellent relationship with. But he would also take photographs and present them in a slightly different way than how photographers would choose to print them. He made certain decisions about the presentation of other people’s work within the space of the magazine,” Wan said.

Even the exacting French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, who coined the term the “decisive moment” to describe that split second when everything that is needed to be captured is in the photo frame, made allowances for Brodovitch. He allegedly would only allow his photographs to be cropped by Brodovitch in Harper’s Bazaar. That was the case with Cartier-Bresson’s image of two sex workers, “Calle Cuauhtemoctzin, Mexico City (1934-35).” Brodovitch had “this ability to get photographers on his side with really quite radical decisions and interventions with their work,” Wan said.

He encouraged students to draw upon their talents, strengths, idiosyncrasies and happy accidents, Wan said. That ideology could have stemmed partially from his interest in the Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti, whose teachings borrowed from Hinduism, Buddhist thought and the notion of decentering, she added.

As for whether “Astonish Me!” will make a case for criticism to challenge people and encourage growth at a time when many professionals and educators only do so cautiously, Wan said, “We are in this moment of reflecting upon intergenerational differences. It goes to a broader point as to how one overcomes disappointment and conflict in one’s life. Part of the reason this exhibition is a challenge and a paradox is that Brodovitch experienced many tragedies including two devastating house fires” that eviscerated much of his personal unique work and works of art that he had been given in exchange by other artists, photographers and designers that he had met over the course of his life, whether that be in Paris, Philadelphia or New York.

The show’s final section delves into “Ballet: 104 Photographs by Alexey Brodovitch,” the only book that he ever made and was released with 500 copies. “Yet, somehow it has become a very important book for many well-known creators today, amongst them Annie Leibovitz, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Martin Parr, Gerry Badger and David Campany,” who penned an essay for the show’s 160-page catalogue. “Again, it raises this idea of a paradox. How is it that something so rare has become so important for many people?” Wan asked. “He only made one attempt at a photo book and it gained such currency and is so well-loved.”

Best of WWD