Why Adelaide Is Australia’s Most Exciting Food and Wine Destination

The revolutionaries of the South Australia wine industry have started to grow up, if not exactly mellow out.

Nine years ago in the Adelaide Hills, just beyond the suburbs of South Australia’s largest city, aspiring vintners Anton von Klopper, James Erskine, and Tom Shobbrock made their first wine together—a rustic sauvignon blanc that willfully ignored the best practices of modern winemaking as taught at the University of Adelaide’s renowned wine program. It was, by normal standards, a mess: cloudy instead of limpid and colored like orange juice cut with water. The winemakers were pleased: they hadn’t intended to make a normal wine.

In the spirit of a garage band planning its first tour, the trio decided to take their weird experiment directly to the public. They named themselves Natural Selection Theory, pulled together outrageous costumes to wear at their public appearances (including hot pants), and piled into a van for a series of one-night bar gigs in Melbourne and Sydney. The wine wasn’t presented in proper 750 ml bottles but was glugged into tumblers from a 23-liter glass demijohn set on the bar. The whole thing—wine and tactics—was punk.

Today, sommeliers might use other words and phrases to describe such a wine, like “natural,” “skin contact,” and “orange,” the vocabulary of an international movement inspired by archaic winemaking practices. Since 2010, it’s come in from the crackpot fringe to reach the edge of mainstream respectability.

Whatever you call it, South Australia has become a global hotspot for experimental winemaking. In particular, a sub-region of the Adelaide Hills called the Basket Range is riding high on a funky, cloudy, chemical-free, minimal-sulfur, high-acid, low-ABV wave. By volume, the output of natural wine in South Australia is vanishingly small compared to the conventional bulk of Australia’s largest wine growing region. Plus, it’s not to everyone’s taste; some people compare it to kombucha or scrumpy cider. And hardly any of it reaches American shores.

Yet natural wine has become a calling card for SA, and the new energy of young winemakers and wine drinkers has helped Adelaide shake off the dust of its dignified but stuffy past and leap ahead of its second-city insecurity to become Australia’s most accessible food-and-wine destination.

(Incidentally, the term “natural wine” is imprecise but generally connotes chemical-free vineyards, low-tech winemaking practices, and little or no added sulfur, although how many parts per million of sulfur is reckoned unnatural is a debate as arcane and heated as medieval theologians battling over angels and pinheads.)

Traditionalist oenophiles who aren’t ready to go natty with the hipsters will find plenty of South Australia wine that hews to more conventional standard of prestige. And before meeting the revolutionaries, I thought I should pay homage to the king. The Grange is a heritage-listed Shiraz blend made at Penfolds Magill Estate, a vineyard property at the foot of the Adelaide Hills that dates to 1841, nearly as old as the city itself. It is a paragon of Australian winemaking, a powerful but controlled show horse, and its high accolades include five perfect 100-point scores since 2008 from influential critic Robert Parker. It sells for $700 a bottle at the cellar door.

More surprising to me was that Penfold’s Magill Estate was only twenty minutes in one direction from Adelaide’s historic city center and twenty minutes in the other to the biodynamic realm of the hill hippies. South Australia’s other key wine regions—the Barossa, Clare Valley, and McLaren Vale—are likewise within an easy drive. Adelaide, in effect, is the hub of a vast vinicultural swath of the state.

As a result, Adelaide combines the culinary good life of wine country with a big city’s energy and variety, as if Yountville had a million-plus residents, a major university, a busy Chinatown, a giant historic food hall, and a culinary legacy shaped by 150 years of immigration from across Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Indeed, Asian cuisines are to Adelaide what Latin cuisines are to Los Angeles: varied (Uyghur, Malaysian), affordable, and everywhere.

That sense of discovery and surprise carried through during my weeklong tasting tour of the surrounding wine regions, with Adelaide as my base. Everything I thought I knew about Australian wines was either incomplete or out of date. “There are so many styles of South Australia Chardonnay, you can’t say you don’t like South Australian chardonnay,” one cellar door manager told me, and the same could be said of the region’s other familiar grape varieties, let alone the oddball plantings of chenin blanc, cabernet franc, sauvignon, and gewürztraminer.

In the end, I took away an impression of multiplicity—multiple cuisines, multiple grape varietals, sub-regions, soil types, winemaking techniques, and indigenous ingredients. As a vineyard region, South Australia is the land of a thousand appellations. Ecologically it’s the junction of the sea and outback. Its agricultural heritage is, for a young nation, deeply rooted yet forward-looking.

“You can’t package this up and ship it to the USA,” said Adelaide-based wine writer David Sly over lunch at Summertown Aristologist, a locavore bistro in the Adelaide Hills opened by von Klopper and Erskine. “To understand this food and wine conversation, you have to come here. If you don’t come to where the wines are being made, you won’t get them. It’s the voilà moment.”

Adelaide

Founded in 1836 as a master-planned city for free citizens—rather than as a penal colony, like most other Australian cities—Adelaide still has residents who retain their founding-family sense of social superiority. That sense of high rank, however, hasn’t traditionally spilled over into the food world. Adelaide’s culinary reputation has been on the rise, however, after decades of eclipse by Sydney and Melbourne. The change is linked in part to the influx of a new creative class priced out Australia’s other big cities. A change in the liquor-licensing laws to favor independent entrepreneurs also led to a boom in small bars and restaurants. Pre-dinner drinks can easily take in classic pubs like the Exeter, wine bars like Hellbound for natural wines, East End Cellars for a vast selection of SA bottles, and a world of craft cocktails at Pink Moon Saloon. The dining scene of the last few years, meanwhile, has been led by Jock Zofrillo and his celebrated tasting menu restaurant, Orana, which focuses intently on native Australian ingredients. To experience the city’s numerous global influences, head to Shobosho for its charcoal-fired izakaya counter up front. There's also Africola — an African-inspired bistro from Marco Pierre White–alum Duncan Welgemoed, where ingenious and sometimes outlandish food — burnt peppers served with squid-ink aioli — plays against Afro-pop interiors by hometown Mash Design. Nearby, Parwana is a longstanding Afghani mom-and-pop shop made electric by mom-and-pop’s creative daughters. It’s got to be the coolest Afghani restaurant in Australia. And at the historic Central Market, along Chinatown’s Gouger Street, follow the locals: the busiest places will be the best.

Adelaide Hills

Many of the notable wineries of the Adelaide Hills—Jauma, Lucy Margaux, Commune of Buttons, Ochota Barrels—aren’t easy to visit, opening their doors to the public only periodically. To taste their wines near where they’re made, go for lunch at Summertown Aristologist, where thoughtful locavore cooking is served homestyle under hanging light fixtures made from glass demijohns. Up the road in Uraidla, winemaker Taras Ochota tucked an Italian brick oven into a deconsecrated chapel for his informal pizzeria, Lost in a Forest. Both restaurants have become de facto tasting rooms for local wines—as well as clubhouses for the winemakers themselves.

Barossa

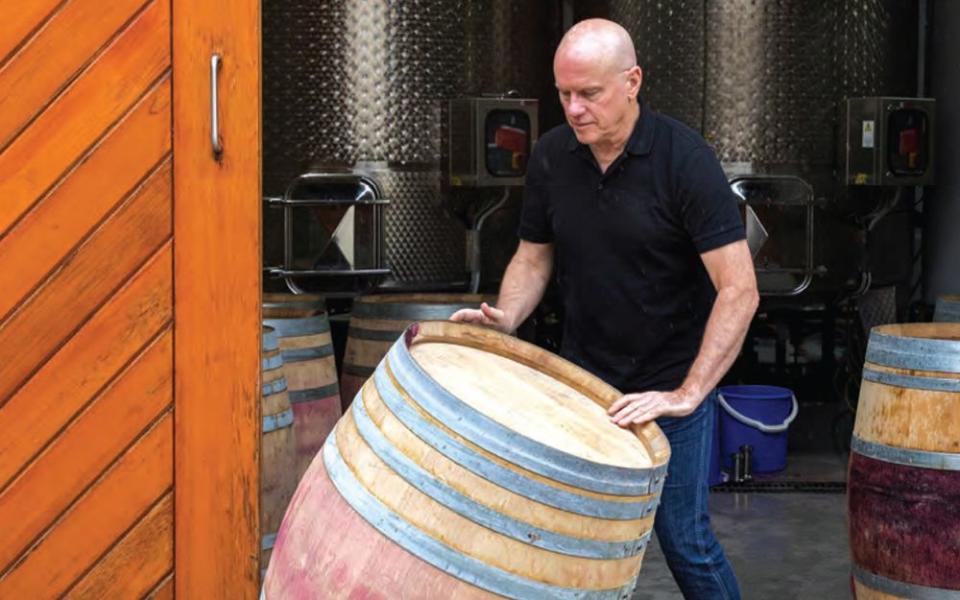

Like Napa Valley, the Barossa’s reputation rests on its collectible cult wines and ambitious tasting-menu restaurants. At Seppeltsfield winery’s stylish restaurant, the focus is on seasonal dishes using local ingredients—one dish of charred rapini with broccoli flowers evoked the blooming rape-seed fields I’d seen on my drive. A lively vermentino and a food-friendly nero d’avola were, in local parlance, “moreish,” as in “give me more.” Nearby, indie winemaker Abel Gibson makes gorgeous, shimmering varietals under the Ruggabellus label. Twelve miles south of here, Tom Shobbrook, one of the leaders of the region’s natural wine movement, recently planted his own vineyard amid a pastoral landscape of grazing sheep and shaggy eucalyptus trees. Barossa also has the finest hotel in the wine country. The Louise is a luxury retreat and tasting-menu restaurant with a suitably regal avenue of Canary Island date palms that flank the approach along Seppetsfield Road.

Clare Valley

If the Barossa is like Napa, then the Clare Valley is akin to Sonoma, an adjacent region with a cooler climate, varied terroirs, idiosyncratic winemakers, and great scenic beauty. The man who put Clare Valley on the map is Jeffrey Grosset, founder of Grosset Wines, who continues his meticulous work with riesling—a grape that’s underappreciated in the U.S., but in his hands yields a precise, bone-dry elegance. (One Riesling he makes goes exclusively to Qantas for its business class service.) Ten miles north, the winery restaurant Skillogalee is in a charming 1853 farmhouse with a lit fireplace in every room and wonderful home cooking, such as pumpkin soup with thyme and chicken pot pie with mushrooms, both flavored with smoky local bacon. And in a place where whites have typically dominated, reds are now trending. Second-generation vineyard brothers Damon and Jono Koerner of Koerner Wine were named Australia’s 2019 Young Guns of Wine on the strength of their lighter, brighter reds made from Nero d’Avola, Sciacarello, sangiovese, and even Malbec.

McLaren Vale

Twenty-five miles south from Adelaide and on the way to the Fleurieu Peninsula—where a ferry launches to Kangaroo Island—McLaren Vale barely escapes the Adelaide sprawl but somehow still feels like far-away wine country. Samuel’s Gorge winery’s authentic setting of protected parkland and mature olive groves shelters a cellar door in a stone-walled 1853 farm shed, where the wines show the cooling maritime effect on red varietals including graciano and tempranillo. Millennial-friendly Alpha Box & Dice kitted out its cellar door with yard-sale antiques. Tattooed attendants pour wines that run a fun gamut from prosecco and all-day rosé to quasi-Italianate dolcetto and sangiovese.