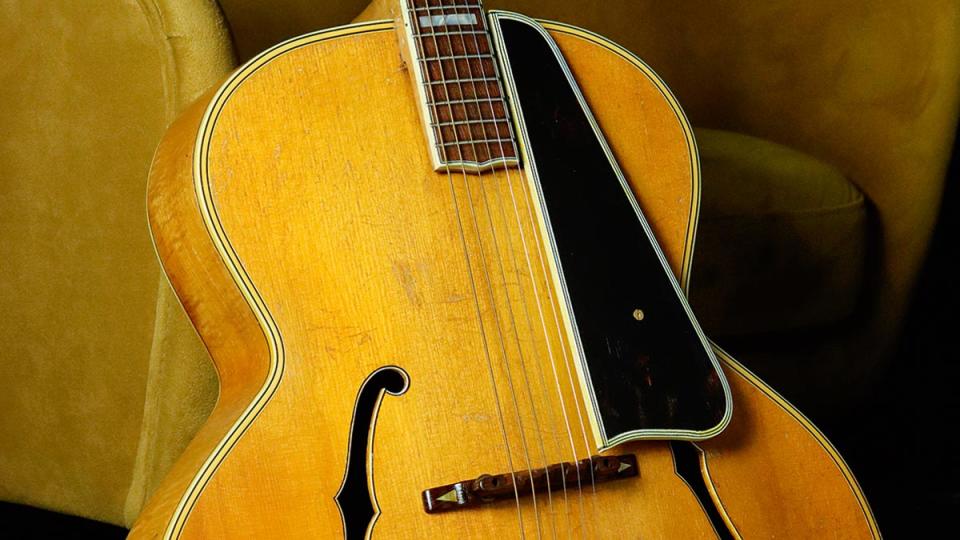

Why the 1946 Stromberg Master 400 is a jazz guitar to rival anything from Gibson and D'Angelico

“Elmer Stromberg made maybe less than half of the guitars that John D’Angelico produced. The serial numbers go up to 686, but they appear to start around 300. It was a really small operation with Elmer and his father, Charles, sharing a workshop in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Charles made drums, banjos and ukuleles, but when guitar became the choice for big bands, Elmer just followed the trend. Elmer probably never imagined he’d end up producing one of the better archtop guitars ever made.

“At first, Elmer pressed the tops and made laminated backs and sides, but he then hand-carved solid spruce tops and maple backs. Having started with cross and parallel top braces – the convention for archtop acoustic guitars – Elmer changed to a single brace that ran diagonally under the top.

“Although the earlier guitars are well regarded and collectible, the golden era for Stromberg archtops is considered to be 1940 to ’55. Production ceased when Charles and Elmer died within a few months of each other; it’s been estimated that only around 150 guitars were made during this period.

“This example is most likely from ’46, but the absence of records, and serial number inconsistencies, make it hard to be exact. Stromberg made several different models, but the Master 300 and 400 were really the ones to buy, and the 400 was the big daddy.

“It’s a relatively plain-looking guitar. The tuners have been changed for a vintage Epiphone set, but the post holes were never altered. I could put a set of Grover Imperials back on it and nobody would be able to tell because there are no extra holes. Despite being very clean, there’s lots of lacquer checking and there’s a small area on the treble bout where the finish is flaking.

“This sometimes indicates water damage, but the original case shows no sign of that and the wood isn’t swollen or misshapen, so it was probably caused by humidity. The headstock has never been broken and there’s a ‘widow’s peak’ on the back of the peghead. It’s actually a veneer overlay, rather than a painted ‘stinger’, and the neck is a maple laminate construction with two stripes of mahogany.

“Combined with a 19-inch lower bout, Stromberg’s single top brace made his guitars very loud and bassy. They used to call them ‘trombone cutters’ because they could compete against the horn section in a big band situation. Players used to pound their guitars and you can see that in any big band footage from the late 30s to mid-40s. The guitars were purely acoustic rhythm guitars that were meant to cut through; they weren’t really looking for tonal flavour.”

“Once guitar amplifiers became available, many of these guitars got DeArmond pickups fitted. They were only using small amps, but they had to keep them turned down low to avoid feedback and all kinds of issues because the tops were so lively.

“Compared with the bassy projecting tone of Stromberg’s single-braced tops, Gibson’s larger archtops leaned towards a midrange tone. The D’Angelicos I find are somewhere in between, with a bit more low-end than the Gibsons and more midrange than Strombergs. A D’Angelico is perhaps the better guitar for soloists. But this Stromberg is so overwhelmingly loud, it’s kind of like a grand piano because it sounds so big.”

“Hank Garland loved his big 19-inch guitars and was one of those players who could meld together country and jazz. Hank signed it on the back and he also signed the case. He had a couple of the earlier G model guitars and a very rare Master 300 cutaway, so I believe he was probably the company’s highest profile customer.

“When I bought the guitar I didn’t pay any premium; it was only signed by Hank Garland and there wasn’t any proof of ownership. But later I was contacted by a gentleman who was managing the sale of Hank’s guitar collection and he was very aware of the guitar. He told me it had been sold by a family member soon after he died.

“I think Elmer was constantly striving for artist endorsements, but Gibson had so many name players signed up. Most of the serious jazz guys were up in New York and they loved the fact that they could go down to John D’Angelico’s shop and walk right in the door. The Strombergs were in Boston, and the bottom line is – had they been in New York, they would have attracted more artist representation and be more widely recognised today.”

Vintage guitar veteran David Davidson owns Well Strung Guitars in Farmingdale, New York.