Why 150 years on, we’re still searching for the real Gertrude Stein

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

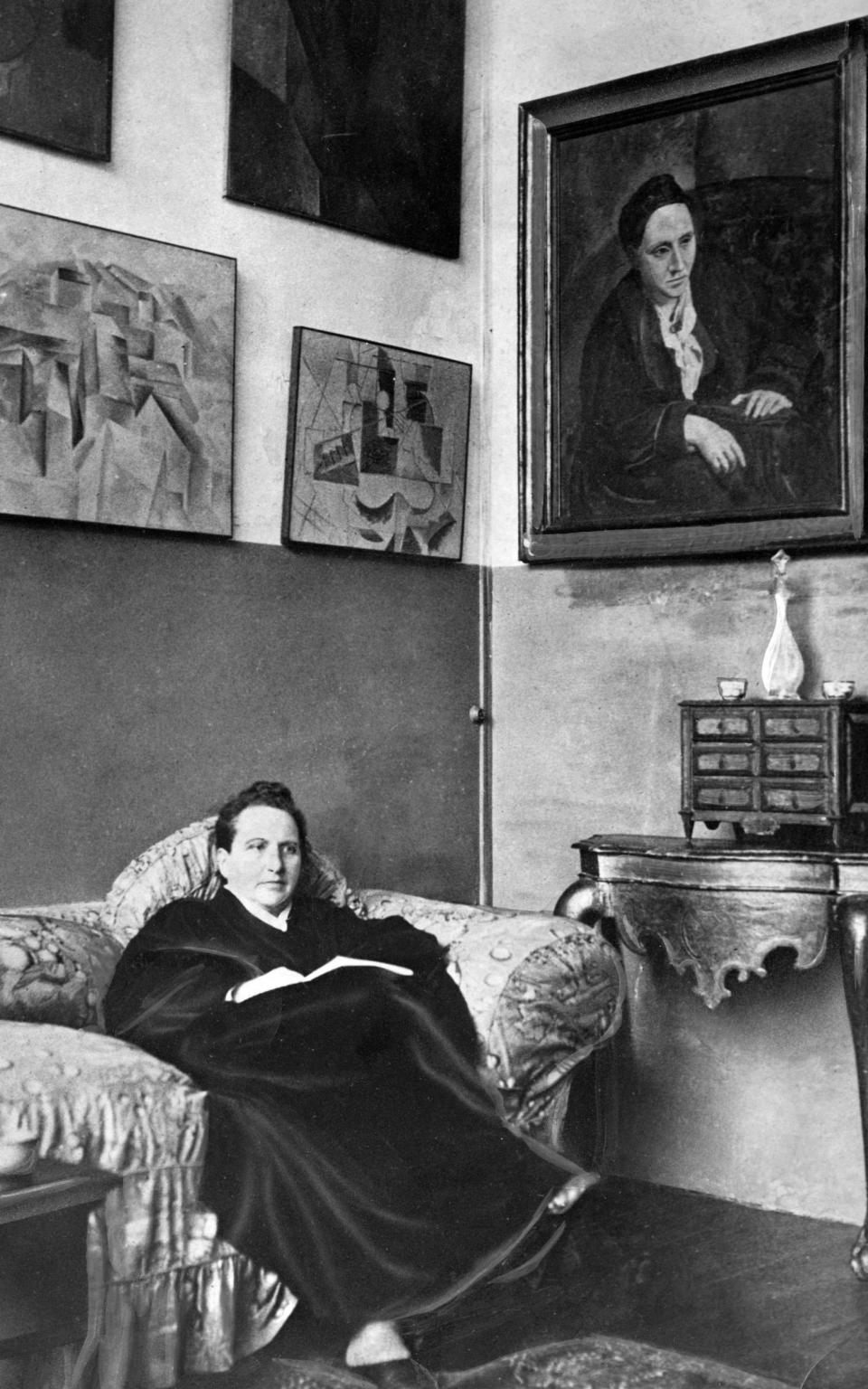

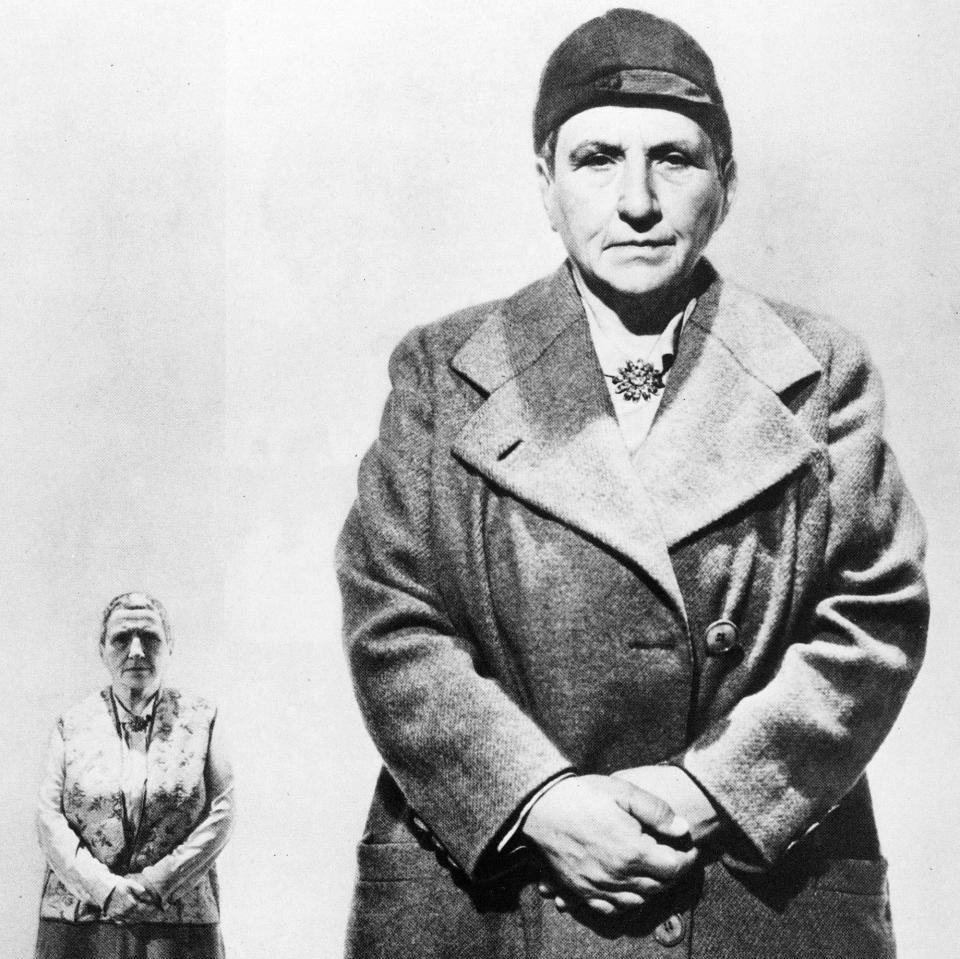

In 1903, Gertrude Stein went to Paris, she would later claim, to kill the 19th century. Her weapons: a Blickensderfer typewriter, a supply of softcover notebooks, and a resolute belief that she was creating literature of groundbreaking importance. She spent her mornings asleep, her evenings entertaining the visitors who flocked to her home to gaze at her unparalleled collection of modern art (Cézanne, Renoir, Gauguin…), and her nights writing furiously by hand, tossing loose scraps of paper to the floor for her partner and de facto secretary, Alice B Toklas, to retrieve in the morning, decipher, and type up. Stretched out on a divan below her own Picasso portrait, Stein was mythic and monumental, a larger-than-life enigma whom friends and detractors viewed variously with amusement, affection and alarm.

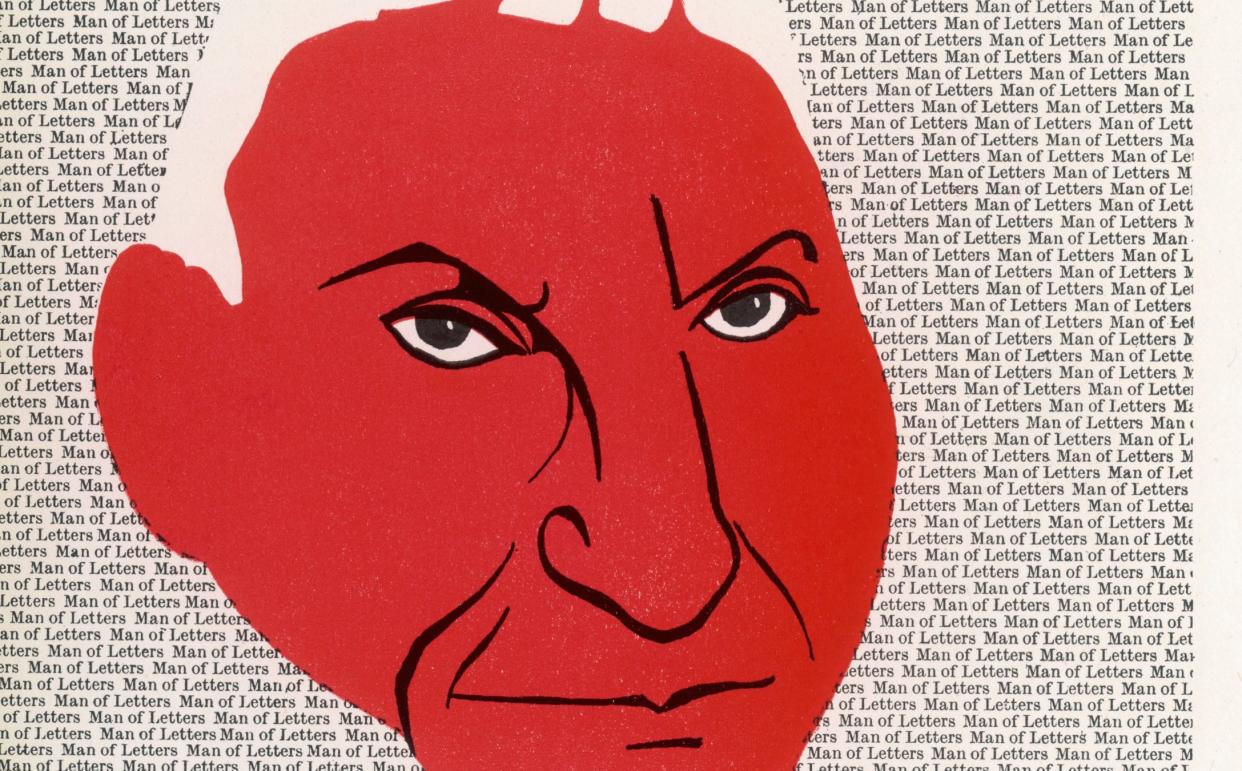

“I have been the creative literary mind of the century,” she insisted towards the end of her life, urging the reading public to “Think of the Bible and Homer, think of Shakespeare and think of me.” Yet even as Stein’s fame rose – reaching a pinnacle in 1933, when her autobiography became an international sensation – her reputation was plagued by uncertainty.

Her writing, replete with wordplay, extended repetition and non sequitur, eschews conventional sense or logic. “Toasted susie is my ice-cream,” reads one of my favourite lines in “Preciosilla”, a poem inspired by the swirling skirts of flamenco dancers; the phrase “pigeons on the grass alas”, from her opera Four Saints in Three Acts – interpreted ingeniously by the choreographer as a vision of the Holy Ghost – inspired a bevy of surrealist Fifth Avenue shop windows when it was performed on Broadway in 1934.

Critics mocked her mercilessly; publishers repeatedly rejected her; readers pronounced themselves baffled. Was this woman a true experimenter who freed language from its formal constraints, or a fraud who knew nothing about the revolutionary art she supposedly championed? An outcast, or the ultimate insider?

Stein spent much of her life in the pursuit of publicity, engaged in the artful process of self-invention. “I always wanted to be historical, from almost a baby on,” she wrote just over a month before her death in 1946, aged 72. From the moment she started writing, she was determined to find an audience for the experimental works she considered her greatest legacy: her epic The Making of Americans, written between 1903 and 1911, which set out to tell a “complete history of every one who ever was or is or will be living”; the word-portraits that attempted to convey a person’s essence without description; and the plays, which sought to “tell what happened without telling stories”.

But it was not until she created her own sepia-tinted legend in The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas – the story of her life as seen, purportedly, through the eyes of her adoring partner – that Stein found the fame she had long craved. During a seven-month lecture tour of America, where she hobnobbed with Hollywood stars and saw her name flash up on Times Square’s electric newsreel, readers went mad for Stein, and demanded more – but not of the avant-garde texts she considered her “real” writing.

Rather, it was the tales of bohemian life in Golden Age Paris that captured – and continue to capture – the public imagination. Stein as the plucky eccentric, whose purchases of bargain canvases by unknown artists called Picasso and Matisse set in motion the artistic revolution of cubism, and whose witty aphorisms and blunt advice kick-started the careers of a generation of American expatriate writers who hung around the smoky cafés of the Left Bank. Stein has consistently been defined not by her own art, but by that of the men around her: trapped in the myth that she herself had established.

Gertrude Stein was born in Pennsylvania exactly 150 years ago today, on February 3 1874, the youngest of five children. Her parents, second-generation German-Jewish immigrants (whose family history and struggles with assimilation Stein would tell, in concealed form, in The Making of Americans), settled in Oakland, California, after a brief sojourn in Europe.

Gertrude and her elder brother Leo pored over books together in San Francisco’s public library, bunked off school to go to the cinema, and tramped for miles through the hills, dissecting the psychologies of fictional characters and family members alike. Gertrude followed Leo to Harvard, where she conducted experiments in William James’s pioneering psychology lab, and then to Johns Hopkins, in Baltimore, where she enrolled on a medical course, soon abandoned.

Leo moved to Paris in 1902, setting up home at 27 Rue de Fleurus and immersing himself in the study of aesthetic theory and modern art. Gertrude joined him the following year, and they spent days rummaging through the heaps of canvases at Ambroise Vollard’s tiny shopfront gallery, where they purchased their first Cézanne.

Within a few years, they had amassed the collection of contemporary works that drew hordes of intrigued guests to their “open house” sessions on Saturday evenings, where Leo would lecture imperiously on the history of art, and Gertrude would answer the door and then sit watchfully atop the solitary stove, legs swinging, and observe people as they moved around the room, absorbed in contemplation of the different impulses that made individuals themselves.

Stein’s work with James had first awoken her to the idea that language was intimately connected with consciousness: that the “infinite variations” with which people repeat the same gestures, mannerisms and patterns of speech could reveal something fundamental about their character, which could, in turn, be expressed in writing. In her novella Melanctha (1905), in The Making of Americans and in a series of short, written “portraits” of friends (the dancer Isadora Duncan, the socialite Mabel Dodge, Picasso and Matisse) composed between 1908 and 1913, Stein set out to express character not through description or action – the cornerstones of traditional narrative – but through the gradual building up and stripping back of language.

Her early style is marked by the rhythmic repetition of single words and phrases, which accumulate power as they recur under different emphasis and with the slightest of variations, to which the reader becomes alert. “Some one who was living was almost always listening,” she wrote in “Ada”, a text obliquely telling the genesis of her relationship with Toklas. “Some one who was loving was almost always listening.”

Stein wanted to express “the complete actual present” in her writing, to convey a sense of ongoing motion that would unfold on the page as if in real time. Above all, she wanted the repetition to shed language of its previous associations, so that her words would mean something fresh and specific, unique to the context she was giving them, and truly alive. When asked, in 1934, about her much-parodied line “rose is a rose is a rose is a rose”, Stein summed up her approach in characteristically bullish style: “You all have seen hundreds of poems about roses and you know in your bones that the rose is not there. I’m no fool; but I think that in that line the rose is red for the first time in English poetry for a hundred years.”

Stein never convinced everyone. “The mama of dada is going gaga,” proclaimed the Marxist magazine New Masses in 1937, while one obituary described her as the “Typhoid Mary of Prose Style”. “Devotees of her cult professed to find her restoring a pristine freshness and rhythm to language,” read another. “Medical authorities compared her effusions to the rantings of the insane.” In the 1920s, Stein was a regular target for lampooning by The Telegraph’s “Peterborough” column: “Personally,” wrote this paper’s esteemed diarist, “I have always held the view that Miss Stein has an enormous sense of humour, and has for years been ‘putting across’ her completely incomprehensible works in order to pull the legs of the more highly browed ‘arties and crafties.’ ”

But to read Stein’s work as a code to be deciphered is to set oneself up for serious frustration – and to miss the exhilarating pleasures she can offer. She is less a writer in the conventional sense than a philosopher of language: words were both her medium and her subject, and to think with Stein as she interrogates their power and potential through cascades of rhythmic prose is an intoxicating experience.

“They live it and I hear it and I see it and I love it and now and always I will write it,” she writes in The Making of Americans, addressing the reader directly as she approaches the fulfilment of her vision. Few writers hold the reader as close as Stein does in this 1,000-page behemoth, which follows a young writer through the vicissitudes of excitement and disappointment as she grapples with the enormous task she has set herself, utterly convinced of the significance of her project. “If you enjoy it,” she insisted, “you understand it.”

Francesca Wade is the author of Square Haunting (2020) and, next, Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife (2025)