The Whole World Seems to Agree: Early Decision Is Evil. I Don’t Think It Is.

If you walk into any expensive private high school today, you’ll feel it: a buzz of anxiety and anticipation. The higher the tuition, the stronger the buzz. Today is the day many Ivy League colleges release their early decision notifications. Other highly rejective colleges have been letting early decision applicants know all week. This annual ritual—where, in exchange for committing to enroll at a college if admitted, early decision applicants find out whether they got in by mid-December—has become such a fraught experience at independent high schools and rich public schools in places like Brookline, Massachusetts, and Greenwich, Connecticut, that in the past decade almost all colleges have started releasing their admissions decisions in the same week, and timing those notifications to hit after school, to spare students the pain of public disappointment. Call it college admissions’ embrace of a kinder, gentler hunger game.

Walk into most public high schools this week, however, and you probably won’t notice a difference. That’s because most students at public schools do not apply to college through early decision. In 2021 less than 10 percent of students at public high schools who used the Common Application to seek admission to 1,000 participating colleges chose to apply early decision. At independent schools—the private schools that charge north of $30,000 a year and pay college counselors more than teachers—about a third of all students apply early decision. Similarly, students from the richest zip codes were twice as likely to apply through early decision.

Early decision pretty clearly favors students who need the least help in getting into college. That is why it has become a target for some college-access advocates, particularly after the Supreme Court ruled this summer that colleges can no longer consider an applicant’s race in the admissions process. A bill in Massachusetts would levy a fine against colleges that offer early decision, and the U.S. Department of Education identified “reconsidering early admissions programs that require students to commit to an admissions decision without the ability to compare financial aid packages” as “part of a comprehensive strategy for

institutions looking to advance diversity.”

Early decision will not go down easily. It is too valuable financially, since it helps expensive colleges enroll students who can pay more than $80,000 for one year of college. The fact that it will be hard to get rid of early decision is no argument against trying to do so, of course, but what if getting rid of early decision actually made things worse at some colleges when it came to goals of enhancing diversity in the student body and facilitating social mobility? Before college-access advocates like myself dig into this fight, we should probably understand whether early decision serves only privilege, the way legacy preferences do, or whether it could have a role to play in making college campuses more socioeconomically diverse.

Angel Pérez, the CEO of the National Association for College Admission Counseling and former vice president for enrollment and student success at Trinity College in Connecticut, understands people’s frustration with early decision and acknowledged in our conversation, “Early decision is not fair. It favors the wealthy.” But he also thinks that most critics of what he himself referred to as a “deeply flawed tool” do not understand the role early decision can play in serving multiple institutional priorities, not just securing revenue from rich families. Or perhaps it would be better to say that early decision can serve multiple institutional priorities because it also serves rich families.

Although early decision might look like little more than a convenient service for the applicant who has their heart set on one college, there is nothing sentimental and very little student-centered about it. Jon Boeckenstedt, the vice provost for enrollment management at Oregon State University, told me, “Early decision used to be considered a benefit to the student; now, while it does give wealthier students an advantage, it’s really mostly for the benefit of the college.”

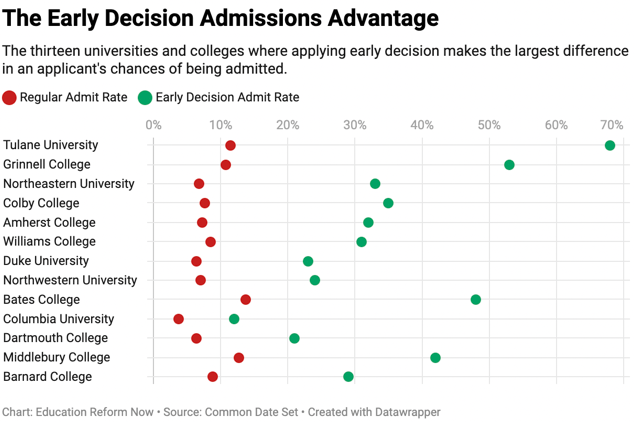

Rich students understand the transactional nature of early decision, which they use not in order to get an admissions decision back sooner but in order to get the admissions decision they want. Applying early dramatically increases their chances of getting in, as much as four or five times what it would be if they applied through regular decision. Among families who often pay multiple sherpas to guide their children through the admissions process, it is common knowledge that the biggest mistake someone applying to places like Tulane, Northeastern, and Amherst can make is waiting for the regular round.

Some of that advantage, to be sure, rests in the characteristics of who applies early: not just students with strong academic support and access to college advising but also legacies, recruited athletes, and students who can pay the full cost of attending schools that cost more per year than the average family of four makes annually. But let’s not kid ourselves about how magical the students who apply early decision are. A big part of the reason they get in is that their commitment to enroll if admitted removes virtually all the risk taken by the admissions office. Under regular conditions, every applicant a college admits is a bet. Admissions officers choose students they think will contribute to the campus community and succeed there, yes, but they also want to admit people who will attend. At all but a handful of colleges, most of these admissions bets do not pay off. The average share of admitted applicants who enrolled at four-year colleges in 2021, or what’s known as the yield rate, was less than 25 percent. Early decision pushes yield much higher, with the added bonus of making a college look even more selective than it is, because it empowers an admissions office to reject even more students during regular decision.

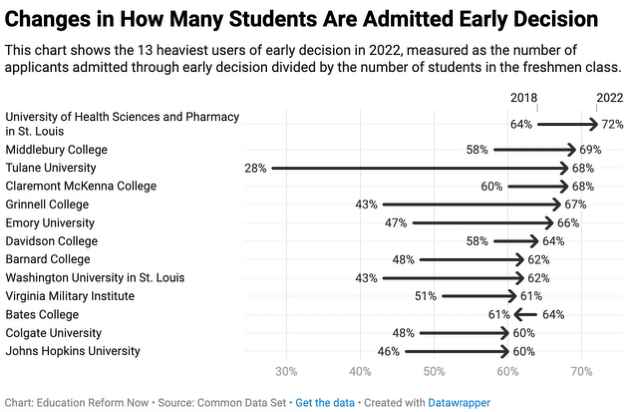

Given these benefits, it should surprise no one that some colleges have leaned heavily into early decision and admitted larger and larger shares of their first-year class this way. In 2018 there were four colleges that enrolled more than 60 percent of their classes through early decision; in 2022 there were 14.

This growth has to be kept in perspective, however, because early decision remains the exception rather than the norm in college admissions. In 2022, out of 2,050 colleges that reported admission numbers to the Common Data Set, which collects a broad range of information about institutions of higher education, just 200 admitted at least one student through early decision. Less than 5 percent of college freshmen are admitted through early decision.

The reason less than 10 percent of colleges offer early decision is that it is not worth it. Boeckenstedt told me, “If your pool is full or even overflowing with highly qualified, wealthy applicants,” you can “install a gate to help you sort them,” but “if your market position is much further down the pecking order; if few students consider you an aspiration school; if the vast majority of your students enroll with financial aid of some sort; or if your admit rate is above 75 percent, you perhaps could see a tiny boost by using ED, but it’s not clear that the juice would be worth the squeeze.”

For very expensive and very desirable private colleges, however, that juice keeps them running. Pérez told me that when he worked in admissions at several highly selective private colleges, he would not have been able to “make [his] class” without early decision. Making a class means, first and foremost, hitting a tuition revenue target that depends on enrolling enough students willing and able to pay the sticker price to attend, but it is more than that. Making a class also means hitting other institutional priorities, which may include enrolling students from low-income households. Securing the bag on tuition revenue during the early admission period is a way to fund students who could not possibly pay anything like the $70,000 to $80,000 a year it costs to attend some private colleges.

Jon Burdick, who ran admissions at the University of Rochester and Cornell University, also pointed to the Robin Hood–like nature of college pricing at highly selective private institutions. Full-pay students help pay for equally qualified, or even more qualified, students who cannot afford to attend. Some institutions use the early decision round to directly enroll low-income students through college-access programs like QuestBridge and Posse and from partner schools and school districts lucky enough to have school counselors with the expertise to know the difference early decision can make in not only an applicant’s chances of admission but also the size of their financial aid package.

One of the problems with early decision is that its power in the application process remains too little understood among students not rich enough to pay for independent schools and private college counselors. Burdick thinks that one way to make early-decision admissions a little fairer is to make early decision “a more transparent process.” He believes that many students mistakenly assume that they cannot afford to apply early decision because they need to compare financial aid packages, but many well-endowed private institutions that offer early decision promise to meet the full financial need of any students they admit.

Even those colleges and universities that want to use early decision without making a good-faith commitment to meeting full need will release an applicant from their commitment if they cannot afford to attend. More students should also know that there is nothing legally binding about an early decision contract. Colleges should publicize the admit rates for early and regular rounds of application and make it clearer that applying early or regular will not affect an applicant’s financial aid. Independent educational consultants are already tracking down those admit rates and sharing them with their clients. Every student and school counselor should have that information.

Burdick and Pérez remain convinced that, for all its flaws, early decision is worth defending, and they worry about the unintended consequences of forcing colleges to drop early decision through legislation. Burdick suggested that “getting rid of early decision could lead colleges to rely more on even worse tools for demonstrating interest,” like personal essays that students might not even be writing themselves, or to use tactics that would ultimately benefit wealthy applicants the most, like offering deeper merit aid discounts to entice enrollment. Pérez suggested that “tying the hands of enrollment managers” by forbidding early decision would be a mistake at the moment that some of them are wrestling with the impact of this past summer’s Supreme Court decision.

Early decision may be a necessary evil at some expensive private institutions in order for them to reach more equitable goals in their admissions process, but the problem is that we don’t know which colleges are using early decision for good. Since 2012, Johns Hopkins University, Washington University, and Middlebury College have all significantly increased the percentage of freshmen they admit who are eligible for a Pell Grant, which is a proxy for low-income status. Does early decision, which all three colleges also use to fill their classes, get the credit? Tulane’s Pell share has declined to single digits over the same period and is among the worst in the nation. Is early decision to blame?

The truth is that we don’t know, which is why the Department of Education needs to start collecting data for early admissions programs, including who applies, gets admitted, or enrolls through early decision. That data should be disaggregated at every point by race and ethnicity and at the point of enrollment by whether a student qualifies for the federal Pell Grant.

Early decision is a bargain made between colleges and applicants. If colleges want to hold on to it, they need to make a bargain with the public and own up to how they are using it. That way, we can see who is using early decision for evil and who is using it for good.