Where Are Fashion’s Connoisseurs?

There’s a lot of chatter, among both the veterans and the very young, about how fashion used to be so great. Even the Zoomers seem to agree that the ’90s, a decade when few of them were even alive, represented a golden era packed with designers whose genius far exceeded that of anyone working today. There are a ton of differences between then and now. But one thing I keep thinking about, particularly as I listen to In Vogue: The 1990s, Vogue’s terrific podcast about that decade, and re-read books by the writer Teri Agins, is that fashion used to be a subculture. Its niche status afforded its arbiters and participants (including shoppers) a reputation of expertise, of connoisseurship. It wasn’t something everyone followed or knew about—and it certainly didn’t need celebrities, because it had its own, in designers, models, writers, hangers-on, and obsessive consumers.

Now, fashion is popular culture, and even casual fans know the big names. Major models are major celebrities, and the most out-there runway pieces appear on athletes, movie stars, television stars, and podcasters. There is more fashion, and more people buying it, or at least paying attention. (I saw a number of non-fashion journalists tweeting the cityscape looks from Virgil Abloh’s Vuitton collection, for example.) We now expect fashion designers to weigh in on politics—back in 1998, you’d never have pressured Tom Ford to opine on Bill Clinton’s sexual indiscretions and impeachment, however raunchy Ford’s work at Gucci was.

Okay, so there’s no Martin Margiela or Helmut Lang, but there are some great designers who are really meeting their moment and adapting to these times, like Rei Kawakubo, Rick Owens, and Jonathan Anderson. Kawakubo and Owens, of course, are veterans. Anderson, who is 36, is the quintessential young designer: a real creative, always in pursuit of and championing ideas, with the mind of a marketer. Twice a year, as Loewe’s creative director, he puts out fashion collections that knock your socks off and get your brain revving, and then throughout the rest of the year he puts out hit bags, cool collaborations, and reliably great projects that provide a foundation of financial stability for his brand.

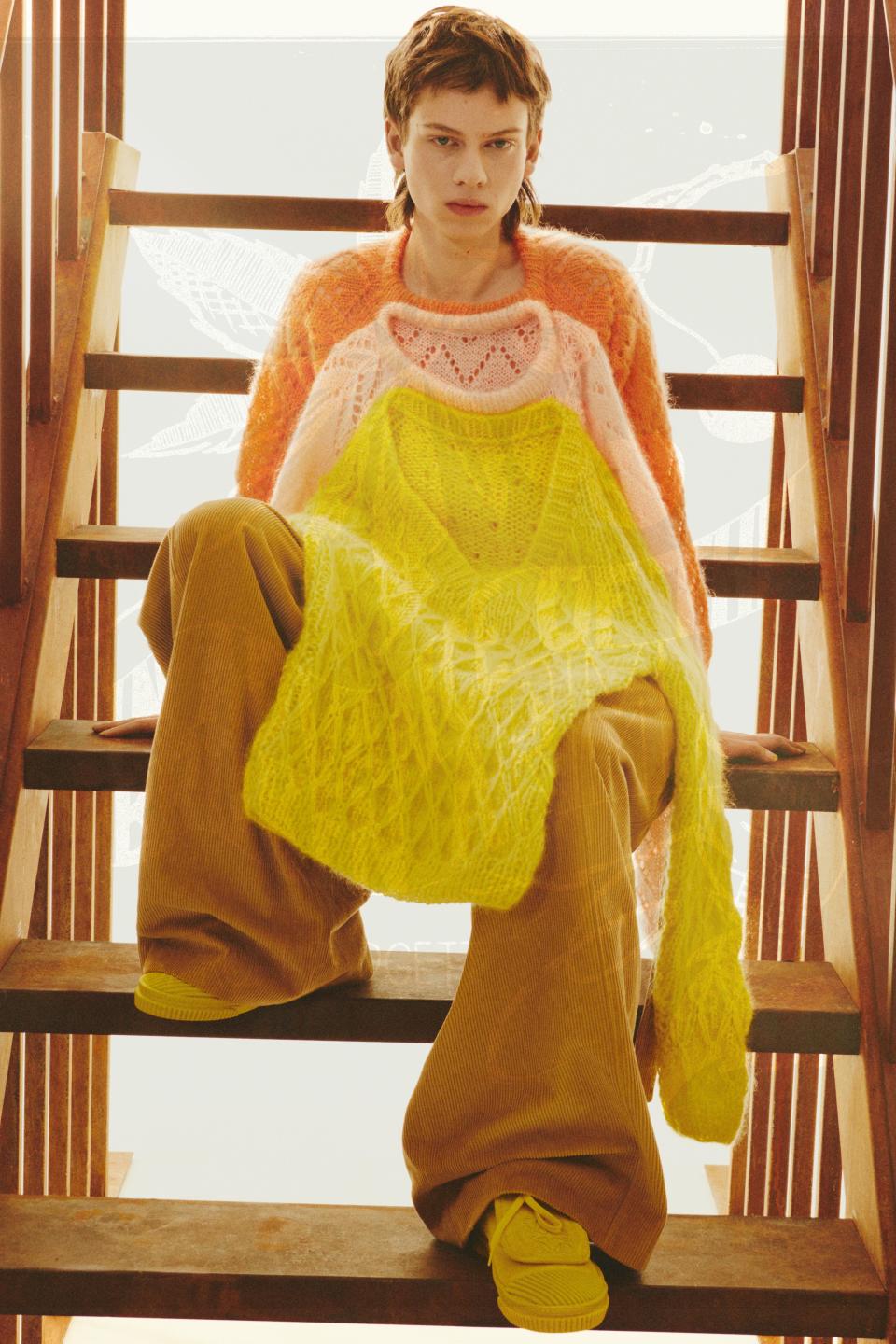

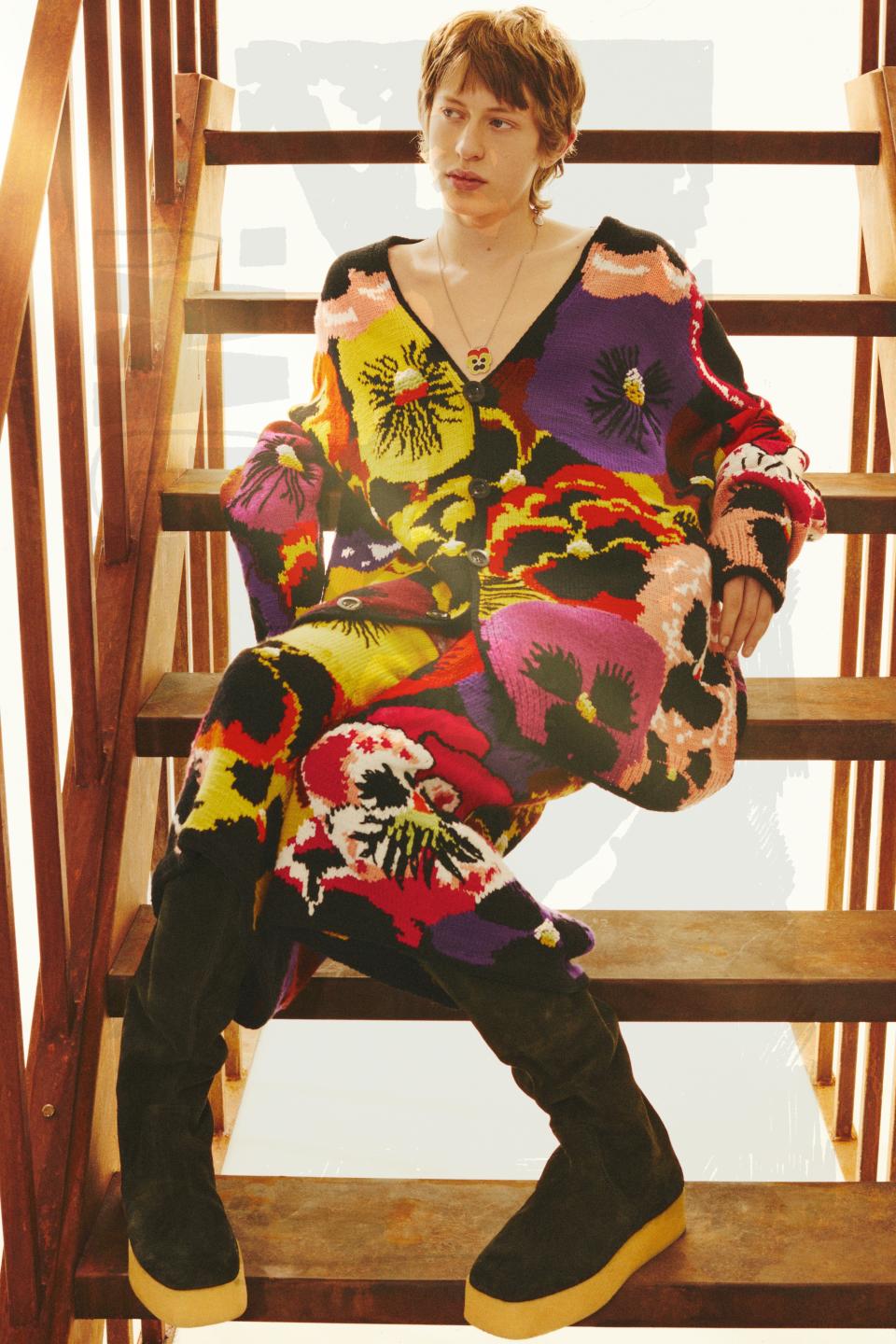

Look at his Loewe Fall 2021 collection and you’ll see what I mean: the beefy, even juicy shapes of his pants, knits, and jackets are architecturally interesting. But they also have the benefit, Anderson pointed out in a Zoom conversation after Saturday’s presentation, of appearing terrific on Instagram, taking up so much of the frame with their enormity. Beautiful, shareable, and covetable, like a sophisticated sugar pink coat with a yellow collar, or cropped leather buckled leather pants, or pansy-print cardigans that a straight and unassuming Mr. Porter shopper will snap up without even considering the wordplay. Drapey trousers that feel like big leg tapestries suggest a contemporary notion of fantasy, which is that the idea of getting dressed and playing with your clothes is an experience. And you know what they say about millennials and experiences: they prefer them to products! The galaxy brain workaround is to make your product an experience!

Many designers this season have taken inspiration from artists. Anderson does this often and very well, particularly because his picks seem to be his real passions, and not just savvy “discoveries.” Here he worked with the estate of Joe Brainard, who’s best known as a collage artist and the author of the funky memoir I Remember. Anderson said Brainard inspired him to think about the pansy—a flower Brainard employed in his work as mischievous queer slang—and the collage. Some of this work was literal: Anderson collaged three sweaters on top of each other, for example. But there was also a more general parallel between both polymaths: “I was fascinated by this idea of someone who was multifaceted,” Anderson says. “This idea of someone who was just as important as a writer as he was an artist.”

Anderson is a great talker—“I’m Irish; that’s all we do”—and he’s always been very open about fashion’s flaws. But he sounded unusually frustrated, even fiery, on Saturday afternoon (“I feel like kind of an angry teenager right now,” he said at one point). “I think in fashion, we were lacking conversation—actual creative conversation,” he said. “We were just kind of like, ‘Well, this brand is so big. Therefore, this is the best collection, and this is how it's going to work.’ The spectacle was the thing. The front row was the thing. Everything was all about the front row. There is no front row now. There is no celebrity to really hold on to.”

He conceded that fashion shows will come back, but they’ll be more considerate, at least for Anderson, of the intended audience and their tastes. “We might need connoisseurship to start back up again. It would be a good thing. Maybe this industry might need more connoisseurship.”

I wonder how many viewers had really heard of Brainard’s work before Anderson’s show—it’s of course okay if they hadn’t, but the purpose should be to inspire, as Anderson said, curiosity, rather than blind covetousness. “I don’t think it’s about being nostalgic,” he said of his Brainard collab. “It’s about learning. Maybe we should just learn to be more curious.” Are we as fashion consumers and thinkers adequate consumers of culture, or adequately curious? Or has the contemporary fashion system bent our minds to think only about the next collection, the artists or writers everyone else is talking about, the creators everyone tells us to pay attention to? “In the beginning of the pandemic,” Anderson said, “everyone was like, ‘Oh, we want the industry to slow down, it’s too fast, and there’s too many collections.’ There was this whole movement that lasted a week. And then it just vanished. We didn't actually question any fundamentals. Like: are there too many brands? Is what’s ‘good,’ [actually] good?”

Sometimes I worry that fashion’s merging into popular culture has meant, perhaps ironically, that people in fashion think too rarely about things outside of fashion. Primarily, fashion, social media, and celebrity culture consumed with representation, and very uninterested in larger questions of fit and design, the process of creative dialogue, and even ideas about the changing standards of beauty. Maybe I’m being too snobby; we also can’t ignore the fact that fashion houses have made it awfully hard or unappealing to be an original consumer with their zillion-dollar marketing machinery. But the result is that many of the great younger writers and thinkers of our time simply look at fashion and shrug, believing it’s better left to the experts or something. Meanwhile, those of us in the industry often struggle to admit that a show or design is bad or uninteresting. I can’t think of any other medium where it’s so scary to admit that you didn’t like something!

A lot of fashion shows since last March—perhaps starting with Alessandro Michele’s Gucci carousel show that made the backstage into the show itself, staged just before the pandemic—has been about fashion, about dressing, about the making of clothing, about the making of identities through clothes. These kinds of shows usually work to confirm our own ideas about the world, or our idealized version of it, and we are perhaps too content to accept that version of things rather than use them as a starting point for something new. An artist, filmmaker, musician, or fashion designer doesn’t have to set off a worldwide trend, or end up as the face of a fashion campaign, to be worthy of our time. Between Abloh, Jones, and Anderson, it seems many menswear designers are envisioning their collections as avenues for discovery, but I found Anderson’s vision of fashion most compelling. Sometimes I worry we are too dedicated to demonstrating expertise than surrendering ourselves to cultivating and developing our own good taste.

After the show, I put on some Annie Lennox, sat on my living room floor, and paged through the Brainard book. It was terrific. Just what Saturdays are meant for.

Originally Appeared on GQ