WhatsApp at work: The dangers and pitfalls of using the app with colleagues

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As the most commonly used messaging app by UK adults, WhatsApp contains multitudes. Our love life. Our mates. Our mother-in-law. Our estate agents. And, increasingly, our colleagues. It’s also a horribly easy place to make a faux pas.

WhatsApp’s quickfire style of chat and speedy sharing functions combine to create a communications minefield, both for work and in social circles. My boyfriend still cringes about the time he left a 30-second voice note on his lads’ WhatsApp group, telling them he was dreading the date he was headed to, feeling desperately hungover and on the verge of vomiting â complete with heavy breathing for dramatic effect. When he didn’t hear back, he spotted he’d sent it to the lady in question â and just as quickly, she’d listened.

Work is rather more high-stakes, of course – as government ministers and advisers past and present are learning this week, as WhatsApp messages from the thick of the pandemic become public knowledge during the reporting of the Covid inquiry. Former chief adviser Dominic Cummings’s messages are perhaps the most shocking, from calling former top civil servant Helen MacNamara a “c***” to denouncing the cabinet as “useless f***pigs”.

On Tuesday, one of Boris Johnson’s senior aides, Martin Reynolds, admitted to having turned on the disappearing messages function to send the PM information, telling the inquiry he could not remember why he had done so. Reynolds insisted that the published WhatsApps are “exchanges which people could have been doing previously by telephone or in corridors”. Yet the clear difference between a cigarette-break grumble about leadership and a written-out WhatsApp rant is that the latter is easily saved and exported – and could become part of the historical record.

The amount of times Covid policies are discussed and minister competency questioned in these chats suggests they were channels for decision-making, not merely social gossip. Former Downing Street adviser Samuel Kasumu insisted: “There is no way that Martin can honestly say that big decisions were not made by WhatsApp – that is a lie.”

As we scroll through our former prime minister denying his wife is running the country, Cummings bemoaning a “terrifyingly s***” cabinet, and the head of the civil service Simon Case declaring “We look like a terrible, tragic joke”, we may find ourselves reflecting on our own WhatsApp-for-work conduct. One might even sympathise, agreeing that the boundaries between work and private gossip are blurred the minute you take things to WhatsApp.

“WhatsApp and Slack [an instant-messaging platform designed for large companies] can be great tools, but organisations need to define what they’re for, and what behaviour is expected of users,” says Claire Warner, founder of workplace culture consultancy Lift. “Is this channel for ideas sharing? Is it for social plans and jokes?” If your company hasn’t provided this guidance, she says, you should be asking for it.

The concept of a “work WhatsApp” remains flimsy; if you take a colleague’s mobile number to plan an after-work drink, and then go on to chat about work, is it considered an official communications channel?

“WhatsApp is generally for personal use, I don’t know of any official business contracts that exist with them,” says HR expert David Rice of People Managing People. This means you’d largely be protected from management asking to see your messages from it; employees within Europe would be protected by GDPR laws. “However, if the company is paying for it – such as Slack or [the Microsoft equivalent] Teams – I always tell people to assume they are reading your messages.”

I had a client who accidentally added me to a group chat with a friend of hers, where she proceeded to give a rundown of her latest date

Will*

However, the possibility that someone could screenshot your private comments exists the minute a professional contact enters your WhatsApps. “You’re allowed to develop friendships at work. But if someone feels uncomfortable and goes to your boss, that is a work issue,” says Rice. “Instant messaging is exactly where things like workplace bullying and sexual harassment can take place.”

There’s no law against gossiping with one colleague about another colleague, but having those comments saved and shared is always a risk. “How well do you know this person?” asks Warner. “It’s far safer to message saying, ‘Do you have time for a call?’, then calling them to vent off the record.”

Of course, blunders happen and it’s usually easy to issue a swift apology if it’s an honest mistake. “I had a client who accidentally added me to a group chat with a friend of hers, where she proceeded to give a rundown of her latest date,” says Will*, 40. “Apparently he wasn’t a ‘f*** yeah’ and wore bad shoes (a ‘red flag’) but still had potential.” Will at least saw the funny side.

But with everyone from tradesmen to tenants potentially in your WhatsApps, it’s more vital than ever to pause and think before sending that aubergine emoji. Georgia*, 32, was infuriated when her landlord told her group of housemates to dispose of some clutter in their property’s basement before they moved (it wasn’t their stuff, she claims). Taking to their housemate group chat, she ranted, “Why does Neil have to be such a bloody p**** about everything?” Of course, it wasn’t their chat but the one the landlord had set up, including himself.

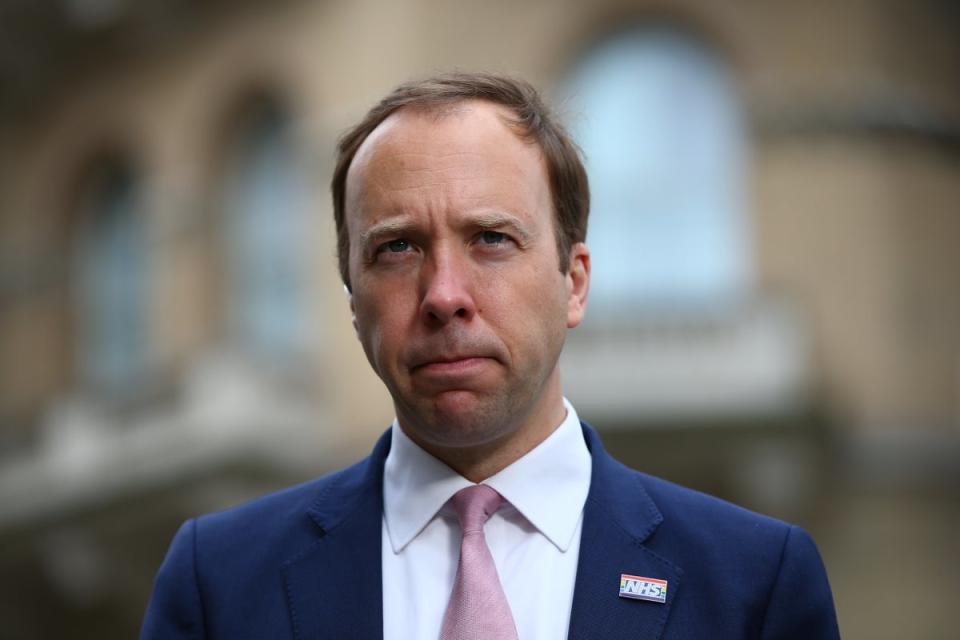

So when does a misjudged punchline become a disciplinary matter? When messaging colleagues, “avoid anything that could be seen as exclusive in terms of diversity, culture, beliefs,” says Warner. Swearing and insults are also a no-no: “I might swear in a face-to-face meeting, among long-term colleagues, but I probably wouldn’t on WhatsApp,” reasons Warner. (See Dominic Cummings’s assertion that we faced going into the autumn with “the c*** in charge of the NHS”, referring to then health secretary Matt Hancock.)

Forwarding on threads from other chats is also rife with danger, says Warner. “There have been some serious ones where restructures have been discussed in one channel, then a whole thread has been forwarded on to the team, including comments where the future of one employee’s position is being discussed.”

Even excluding a colleague from a WhatsApp group could come back to bite you. Last month, plumber Mark Brosnan was awarded £130,000 after a judge ruled that it was discriminatory for his colleagues to have left him out of their work chat. Mr Brosnan claimed he missed out on “important safety information” due to being excluded from the group after missing some work due to a back injury.

Perhaps aware of its part in these snafus, WhatsApp last year added an “undo” function to its “delete” option â if you meant to click “Delete for everyone” but clicked “Delete for me” instead, you can now undo that at the bottom right of your screen. Disappearing messages were also added in 2020; only available for image sharing, they’re unfortunately easy to use accidentally, since the “1” icon you’d tap sits right beside “send”.

The government’s use of WhatsApp as their channel of choice makes Rice instantly sceptical. This was no panicked substitute for email. “My gut feeling is that they felt WhatsApp’s encryption and security would protect them from outside eyes,” he says. The use of disappearing messages only adds to the incriminating feel of the exchanges. “Why would you need information to disappear? If it’s a situation where someone may need to see the paper trail to know what happened, it’s the same as shredding documents.”

Even if you have nothing to hide, separation of church and state is ideal. Warner tells me that she has a folder of all work-related comms apps, such as email and Slack, “and at the end of my work week, I move it several screens away from my main home screen for the weekend, so it’s not even on my radar,”.

In short: WhatsApp and the workplace are a match made in hell. Both experts recommend asking to use a more formalised work platform. “Apart from anything else, I don’t want colleagues in my WhatsApps when I’m on holiday,” observes Rice. “But it’s also all too easy to mix up conversations, run into trouble with the gif library, or even lose track of important information or documents.”

When you’re striking up friendships with colleagues, WhatsApp may seem temptingly off the record. “But think of it as the digital pub,” says Rice; getting hauled in front of HR is still a possibility. In colleague hangouts physical and virtual, it’s wise to watch what you say.

Of course, the beauty and terror of WhatsApp is that we use it for everything else, too. There’s no switching it off for the weekend. That’s when we’re just getting started. Stay safe, people!

*Names have been changed