Whatever Happened To Eggnog Parties?

These events have a long history. How should they be viewed today?

Getty Images

Hundreds of eggs. Crates of liquors. Pounds of sugar. Gallons of milk and cream. Eggnog parties were once a staple of Christmas in Alabama, but the labor behind the beverage complicates its associated merriment.

As polarizing as the drink might be today, eggnog was the height of festive luxury in the 19th and early-20th centuries. "An Alabama eggnog is one that caresses the palate with velvety gentleness," journalist and author Jack Kytle explained in the late-1930s, "and then once it is within the stomach, suddenly it becomes the counterpart of a kicking mule. It is a fluffy, saffron-colored beverage, delicate in fragrance, daintily blended, and pungently persuasive."

Antebellum plantations and homes in Alabama, such as Buena Vista, Gaineswood, Rosemont, Roseland, among others, spared no expense and served the drink in massive quantities—and, Kytle tells us, always with "fruit cake, Lane Cake, coconut cake, and salted nuts."

According to Myrtle Miles, the coordinator of Alabama’s contribution to the ambitious America Eats Project—a Works Progress Administration (WPA) project to collect first-hand accounts of America’s culinary traditions—eggnog was indispensable, “as much part of Christmas as a tree,” in her words.

Often overlooked, however, are enslaved and formerly enslaved African Americans and their labor in our understanding of these traditions. Their voices are not perfectly represented in the WPA files, but are, nonetheless, key to Kytle's research.

In his work for the America Eats Project under Miles’ direction, he spoke, for example, with "an eggnog specialist," an elderly Black man, Nat, who recalled having prepared the drink for more than 60 years. Nat's skill was one shared with other Black Alabamians, who, Kytle writes, were "very proud in a dignity of their roles in keeping burning this light of tradition" and "who remain unequaled at their art of preparing nog." (Many of Kytle's descriptions in his America Eats Project writings carry themes like that of enslavement and the planting system after the end of the Civil War being examples of the "benevolence" of White planters and slave owners. We recognize that this was in fact not benevolence. However, his writings remain valuable to understanding this period of Southern history, as few other projects attempted to gather first-person accounts of slavery and formerly enslaved people.)

Aware of their skill, these Black men and women mused that White people wouldn't be able to maintain this hallmark of Christmas celebrations without them. Behind the scenes, Black laborers carried out the work of gathering, preparing, and balancing eggnog's indulgent ingredients.

* * *

Eggnog has long been the frothy centerpiece of Christmas in the Southern U.S., though its origins lie elsewhere. Related to medieval posset, a hot beverage that mixed curdled dairy products with ale or wine, eggnog was reserved for affluent British people.

Spices like nutmeg and cinnamon signaled the wealth they acquired through trading and extraction routes. Posset-related beverages became widely available in North America from the 16th century onwards.

Similar Christmas drinks that used rum and sugar are recorded from the 17th and 18th centuries in the Caribbean, the result of heavy investment in, and extraction from, plantations.

In antebellum Alabama, eggnog parties flourished at Christmastime. Recipes tend to include a mix of spirits—rum and brandy, whiskey and bourbon—and they show how planter families responded to fluctuating markets. In the 17th and 18th centuries, enslavers swapped expensive crates of whiskies and scotches from Ireland and Scotland for cheaper rum, a product of Caribbean slave labor, and from the late-18th century, they began investing in the domestic distillation of bourbon and moonshine.

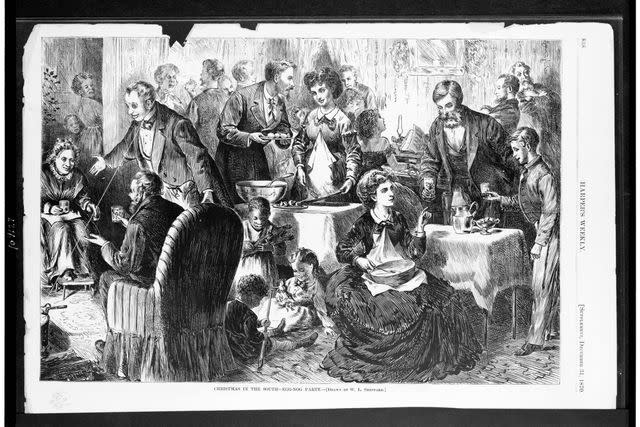

An 1870 wood-cut print, "Christmas in the South–Egg-Nog Party," published in Harper's Weekly, conveys the commotion of such gatherings: Well-dressed guests chat animatedly near the fireplace and sing around a piano haloed in candlelight. A large, festooned bowl of eggnog sits on a table, its contents distributed in glittering cups.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Another interaction underscores the nearly invisible laborers who toil during this jovial gathering. Below the bowl of eggnog, a small Black child carries sticks of firewood. In contrast to the other children—one wears an elegant jacket and the other sits in a ribboned dress—he wears a simple woolen shift, indicating his servitude. In the background, a Black woman's gaze cuts through the crowd; she watches the boy in the center of the room, and the eggnog, before moving to her next task.

Forced laborers not only oversaw the smooth performance of this key social event, but they produced eggnog's ingredients and crafted the drink on an industrial scale. Recipes start with one hundred eggs, and they were made without the aid of modern machinery.

Eggnog was also distributed as a yearly gift from plantation families to their enslaved workforce. Carrie Mason, of Milledgeville, GA, said that her mother's enslaver gave eggnog to everyone, and later, as a freedwoman, she bought this richly caloric drink for herself.

Recent studies of Christmastime in the South, however, question the ubiquitous image of a cheerful holiday plantation. Enslaved people received eggnog at the cusp of the New Year, when Alabama's largest slave auctions took place and families would soon be separated. "Just as it is impossible to separate slavery from Southern history," writes Robert E. May in Yuletide in Dixie: Slavery, Christmas, and Southern Memory, "so is it impossible to separate human bondage from the history of Christmas in the American South."

* * *

Alabama eggnog parties have fallen from popularity, of course. Instead, plantations and grand residences that once hosted them invite the local community and tourists to "step back in time" and attend holiday teas, galas, and candlelit tours. This stepping back in time is not welcome or comfortable for many.

It's perhaps also not ethical, says Camille Goldston Bennet, the founder of Project Say Something. Bennett co-signed a letter that condemned antebellum-themed Christmas events organized at Belle Mont Plantation in Colbert County, Alabama. "I don't know that it is possible to combine something celebratory with all of the atrocities that happened there...especially knowing that over 100 Black people built it and were held captive in that space."

An honest portrayal of Christmas traditions would confront and include the memories and experiences of enslaved people, like the eggnog specialists: "If we are working within a framework of remembering, acknowledging, and reckoning," offers Bennet. "Then plantations can be a site of healing. They can be transformative. A lot of museums and spaces reckon with really painful history. And they inspire people to be catalysts for change."

Bio: Kristen Streahle is an expert in medieval Sicilian art and architecture. She taught in the department of art and art history at Hollins University in Roanoke, Virginia, and she was the co-director of the Small Cities Institute. She also works in communities around the country to shift policy and urban design toward increasing food accessibility and was an organizer of the Resilient Roanoke Roundtable.

For more Southern Living news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Southern Living.