I Went On a Road Trip From Chile’s Atacama Desert to Bolivia’s Salt Flats — Here’s How You Can, Too

The high-altitude route is one of the most spectacular — and inhospitable — on the planet.

Nick Ballón

A flamboyance of James's flamingos on Bolivia's Laguna Colorada.I caught my breath as the flamingos suddenly set flight over Laguna Colorada, a rust-colored salt lake in southern Bolivia. All afternoon the rare birds had been standing, rump-up, head down, busy eating the algae that turns their bodies pink. Then, disturbed by a grazing vicuña, the flamboyance, as a flock of flamingos is known, took off.

Hundreds, if not thousands, of the birds soared, low and heavy, over the water, which stretched out in front of me like a pool of molten brick, and careened onward toward distant, snow-speckled hills. Up to 40,000 James’s flamingos — roughly half of the species’ entire population — can gather around this shallow salt lake on Bolivia’s Altiplano, also called the Andean Plateau.

Other than my guide, David Torres, I was the only human around to witness this extraordinary spectacle. Walking this part of the Andean Plateau with Torres felt like exploring the surface of some foreign planet where the ground is white and the water is red. As I stood 14,000 feet above sea level, feeling the heat of aggressive sunbeams on my cheeks, I felt so close to the sky it was like I’d left Earth entirely.

Nick Ballón

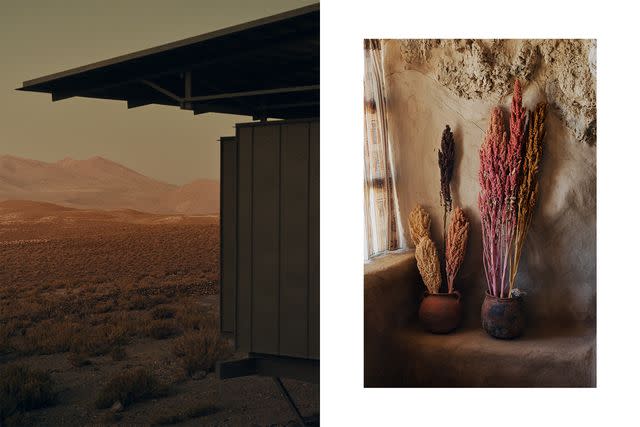

The view from a guest room at Explora's Ramaditas Mountain Lodge, in BoliviaIn reality, I was beginning a weeklong journey along a portion of the Qhapaq Ñan, a road system of the ancient Incan Empire that extends more than 18,600 miles across six countries. Torres was to usher me on a travesía, the Spanish word for a long crossing or journey through a wide expanse of terrain, that would cover 300 miles of the route. Caravans used to follow this path through Bolivia and Chile, their llamas carrying military supplies, precious metals, cocoa, and textiles; travelers would exchange languages and cultures along the way. The goal of the travesía was in part to shine a light on the network of paths that, along with the culture of the Andean Aymara llama herders who still use them, is fading from existence.

The adventure-hotel brand Explora launched this travesía, which would take us through one of the planet’s most austere landscapes, in September. It aims to make the famously spectacular (and notoriously uncomfortable) backpacker circuit between Chile’s Atacama Desert and Bolivia’s Salar de Uyuni salt flat more comfortable than it has ever been. Guests are conveyed over all-dirt roads in latest-model Land Cruisers with padded leather seats and stay at a series of cushy lodges fitted with Wi-Fi, 24-hour electricity, and hot showers — all previously unheard of at these altitudes.

"Walking this part of the Andean Plateau with Torres felt like exploring the surface of some foreign planet where the ground is white and the water is red. As I stood 14,000 feet above sea level, feeling the heat of aggressive sunbeams on my cheeks, I felt so close to the sky it was like I’d left Earth entirely."

Nevertheless, I knew that the journey could be physically grueling. There would be slap-you-in-the-face winds, zap-you-dry sunrays, freeze-your-teeth temperature drops, and clouds that would swirl like cartoon dust devils. The logistics would be equally wild: food would be brought in from Uyuni, in Bolivia, and we would carry four drums of fuel on the Land Cruiser’s roof because there would be no gas stations for a week. Even intrepid backpackers typically linger no more than a night or two in this area, but I’d be spending six nights above 12,000 feet, traveling slowly, riding an ethereal Andean high.

One Day Before Departure: Base Camp in the Desert

The Atacama is not the colorful American desert of cowboys and tumbleweeds; to me it felt emptier, more wild. But there are oases, like the Chilean town of San Pedro de Atacama, that are startlingly green, populated by wayward llamas and yatiri (traditional Atacameño healers who, legend has it, acquired their powers after being struck by lightning).

San Pedro de Atacama is considered a gateway to this desert and the Altiplano, and that’s where my altitude acclimation began. Base camp was Explora Atacama, a 50-room lodge with an observatory, two saunas, and four lap pools half-hidden amid swaying pampas grass. The restaurant serves dishes like crisp pan-fried trout and octopus in olive sauce paired with grassy Sauvignon Blancs from Chile’s San Antonio Valley or peppery Carmenères, the country’s popular red wine. Amid all this comfort, the only downside was that Explora Atacama is located at just 8,000 feet above sea level, which meant I had to spend lots of time away from my plush room — styled in cool, natural tones and warm Andean textiles — and instead go out hiking to prepare for the higher altitudes we’d soon encounter.

Nick Ballón

From left: The Licancabur Volcano looms over Explora's Atacama Lodge, near San Pedro de Atacama, Chile; a chef prepares breakfast in Chituca Mountain Lodge's open kitchen.For my first excursion, Torres led me up to 14,000 feet to view the Tatio Geysers, the highest geothermal complex in the world (and the largest in the Southern Hemisphere). The five-mile trek began at an apacheta, a type of stone tower unique to the Andes where, Torres told me, travelers traditionally make offerings of coca leaves for safe passage. Then we descended to the salty Río Blanco and followed its path past spurting geysers and pits of burping mud pirouetting toward the sky. A faint smell of sulfur filled the air. In some parts, the river had veins of brick-red bacteria snaking along its surface like licks of fire.

“This one looks like a portal to the underworld,” Torres said casually, stepping around a steamy cauldron. Having guided visitors across all corners of the Andes for more than a decade, there was an ease about him that soothed me. He seemed to thrive in this complex, uncomfortable landscape, telling me anecdotes and folk stories about what makes it so remarkable.

Day 1: An Artisan Shelter

Nick Ballón

The lounge at Ramaditas Mountain Lodge, in Bolivia.Torres and I woke early the next morning — he, bright-eyed; me, a bit slow-moving after my first encounter with the altitude the day before. We traveled east into Bolivia at the Hito Cajón Pass, turned north from there to ogle the flamingos at Laguna Colorada, then completed the 146-mile drive past the puffing Putana Volcano to Explora’s new Ramaditas Mountain Lodge, a four-room eco-shelter at 13,370 feet.

From the outside, Ramaditas looks like something from a space colony: stilts hold up two long metallic rectangles, one containing the guest rooms and the other a large common area. “We wanted a type of construction that has a low impact on the territory,” Jesus Silverth, Explora’s head of services in Bolivia, explained of the ocher-painted structures, designed by Chilean architect Max Núñez. “If we had to close tomorrow, we could pull up these modular constructions and the effect on the land would be minimal.”

"“This one looks like a portal to the underworld,” Torres said casually, stepping around a steamy cauldron. Having guided visitors across all corners of the Andes for more than a decade, there was an ease about him that soothed me. He seemed to thrive in this complex, uncomfortable landscape, telling me anecdotes and folk stories about what makes it so remarkable."

Inside, the walls lined with local mani wood soothed my sun-stricken eyes, while bath products made with the citrusy desert herb rica-rica eased my cracked skin. Paintings from Chilean artist Claudia Peña depicted the llama caravans that originally forged our route, while the weighty tableware and toquilla palm textiles that accompanied our family-style meals came from Bolivian ceramist Marcelo Terán Mitre and art collective Artecampo.

Nick Ballón

A sunrise breakfast on the salt flat.Nearly everything in the mountain lodge was sourced from Bolivia, like ingredients for the dishes designed by chefs Mauricio López and Sebastián Giménez of La Paz’s Restaurante Ancestral, whose meal-planning decisions are guided by the fact that the nearest supermarket is six hours away. I ordered a quinoa bowl layered with smoked trout and minty huacatay pesto, and a soup made with ocas, the sour Andean tubers — all served family-style and prepared by a staff of three hailing from the nearby Villamar community. Even the post-hike IPAs (from Cerveza Bendita), dinnertime cabernets (from producer Marquez de la Viña) and breakfast coffees (from the subtropical Yungas region) were Bolivian.

More Trip Ideas: I Went on My First Solo Hiking Trip in Peru — Here's How You Can, Too

The team behind Explora’s luxurious accommodations always lets the landscape be the protagonist, choosing minimal interior furnishings and muted tones that don’t detract from what lies beyond. At Ramaditas, I peered through the wall-to-wall window in my room as the setting sun turned the small lake below into a liquid mirror.

Several hours later, I was skimming the surface of sleep, dreaming wildly and waking often, as one tends to do at high altitudes, when I caught a glimpse of the Milky Way outside my window. Even in my half-awake state, I knew that I wasn’t looking up. I was seeing it reflected on the lake like sprinkled glitter.

Days 2-3: Echoes of the Past

Our Land Cruisers created clouds of dust that signaled our arrival everywhere we went. Not that there was anyone around to see them; Torres, our driver, Cesar Cruz, and I saw no one else as we diverted from the old caravan route we’d been following to places like Pastos Grandes. One of the world’s largest calderas, which form after a volcano erupts, Pastos Grandes is a giant earthen bowl measuring 37 miles across. At the bottom, streams of water cut through the salty white ground.

Related: 12 of South America's Most Epic Hikes You've Never Heard Of

“If an eruption like the one that created this place five million years ago happens again, we’re all gone,” Torres told me on another hike later that day, which took us up to a cathedral-like complex of columnar rock formations called hoodoos. “It would be a mass-extinction event that would end life in the Americas as we know it.”

That day, Torres and I ate a picnic lunch of protein-packed grain bowls next to rock paintings believed to have been made hundreds of years ago by the Mallku-Hedionda people. These nomadic tribes lived from 2,000 B.C. to A.D. 500 — well before the Incan Empire, which hit its heyday in the 15th century — herding llamas along paths that later became part of the Qhapaq Ñan road system. Behind us, volcanic boulders the size of cars sheltered yaretas, chartreuse cushion plants that smelled like pinecones. Torres pointed out other aromatic bushes, such as tola, lampayo, and pupusa, used in local teas to help with altitude sickness and digestion.

Nick Ballón

From left: The Chituca Mountain Lodge on Bolivia's Altiplano, with its views of the Andes Mountains, is a stop on Explora's travesía expedition; inside Bolivia's Las Galaxias Grotto, once used for Indigenous burial ceremonies.The landscape had become newly animated with tall cardon cacti by the time we carved dust trails north to the Chituca Mountain Lodge, our second mini-resort. The dark green building looked like part of the landscape, surrounded by rock and scrub. Inside, Chituca was like a mirror image of our previous shelter, except this property overlooked a distant salt flat.

That night, trying once again to sink into a real, deep sleep, I ended up instead reflecting, astounded, on how remote our location was. The nearest big town was three hours away. The isolation wasn’t like what I’d find in a jungle or on an island or amid dense forest. I was up-in-the-clouds apart. Not that it scared me; I was thrilled. All that space. So much silence to fill. It seemed almost unfair to be on the other side of a giant glass window looking out over such a relentless and uncaring terrain while enjoying incredible comforts. It felt like one of the greatest luxuries on earth.

Day 4: The Highest Summit

Nick Ballón

Descending the slope of Irruputuncu Volcano.The Andean mountain cat clambered up a hill in a huff the second it sensed our arrival, using its bushy tail to balance as it leaped from boulder to boulder.

“Gato andino!” Torres yelled, incredulous.

Our driver, Cruz, was surprised, too. Born in the area, he’d never seen one of these felines, which are only slightly bigger than house cats but have startling, leopard-like coats.

“They’re even harder to spot than the puma,” Torres said, offering me his binoculars. But the cat had disappeared into distant shrubs by the time I could focus. All I could see was its prey: viscachas, rodents easily mistaken for rabbits.

We had risen early that day to make a westerly detour toward the Chilean border to climb Irruputuncu, a nearly 17,000-foot volcano — and the pinnacle of the travesía’s acclimation efforts.

As I walked, the most potent effects of the high altitude, which I’d managed to avoid so far, washed over me in waves. I could feel the limited oxygen altering my state of being to the point where I was convinced I had become a less capable version of myself — light-headed, weak, and short of breath. But I also knew these aches were worth the chance to see what lay ahead. As Torres had taught me, I moved slowly, breathed with intention, and drank water greedily.

Nick Ballón

From left: Hiking the Irruputuncu Volcano, in Chile, amid its yellow sulfur-rich gas; bathing in the Puritama Hot Springs at Atacama Lodge.Two hours later, we cautiously crested the lip of the active volcano. Peering into the crater more than 100 feet below, we gasped when we saw its far edge, which, laced with sulfur, glowed an unnatural yellow, the color of highlighters and running shoes. A fury of pungent smoke spewed from competing vents. At times, the air became so thick it seemed to block out the sun.

Turning back, we slid-jumped down Irruputuncu’s sandy slope as if we were descending a giant dune. A surprise awaited me — nearby, we took a dip in a natural pool filled with bathtub-hot thermal water, breaking the hydration rules with celebratory cervezas.

Day 5: Reaching the Salt Flat

I could barely open my eyes — that’s how bright it was on the Salar de Uyuni salt flat, a staggering expanse of 4,086 square miles (more than twice the size of Delaware). The color wasn’t the bluish white of snow and ice, but rather a radiant, pink-hued ivory. It rippled like the ocean and felt, as I walked across in my boots, like broken glass.

After a quick photo stop, we climbed back into the Land Cruiser and raced northward through the emptiness. The farther we drove, the fewer features — bushes, boulders, buildings — dotted the landscape until, eventually, all I saw was white. Freed from rocks and dust, we moved more quickly than we had all trip, at more than 60 miles an hour. It felt liberating to accelerate after days of slow walking.

Related: 16 Best Hot Springs in the World With Incredible Views

Eventually, we came to a promontory of rock, which is called Fish Island because of its elongated shape. We hiked to the top. For the first time in four days, we were no longer alone. The town of Uyuni, 70 miles away, has an airport and a burgeoning tourism industry catering to travelers coming to explore the salt flat. We watched as 4x4s containing other visitors appeared to crawl like tiny ants across the salar. “You completely lose perspective here,” Torres explained of the illusion. “Things that look close are actually very far away, and a mirage effect plays with your mind because Uyuni is so different from what our brains are used to.” Neil Armstrong became so fascinated with the way the Salar de Uyuni reflected the sun from outer space, Torres added, that the astronaut visited it in 1969, just a few months after walking on the moon.

Nick Ballón

Stopping for lunch on Bolivia's Salar de Uyuni salt flat.If we squinted, we could just make out the lithium mines, which grow by the year in Uyuni’s southeastern corner. The metal from the mines, which is expected to power electric cars, could potentially bring great wealth to the Uyuni region and fuel an energy transition meant to combat climate change. But Torres told me there were already fears in the area that the water needed to extract this “white gold” could irrevocably damage the fragile ecosystem, as well as the lives of the humans and animals that depend on it.

“The salar is our treasure,” Cruz told me as he drove toward Explora’s Uyuni Lodge, our last stop on the trip. “It’s our pride. It’s something that’s always been present in our lives. But who knows what will happen in the coming years?”

Days 6-7: The Roof of the World

My last days on the travesía took on a slower, easier pace. Near the base of the dormant Tunupa Volcano, where Uyuni Lodge is located, Torres and I hiked a remarkably preserved path hewn from stone for the Qhapaq Ñan.

We climbed up terraced fields of quinoa peppered with scarecrows. Torres was jovial as always, chatting with elderly farmers whose faces had been wrinkled like cracked leather by the fierce Altiplano sun. I was feeling chipper, too, finally at ease with the elevation. Remembering my challenges with altitude in the days before, I felt a great deal of respect for the locals who use these cloud-hugging routes on a daily basis — just as generations of their ancestors have done before them.

"I could barely open my eyes — that’s how bright it was on the Salar de Uyuni salt flat, a staggering expanse of 4,086 square miles (more than twice the size of Delaware). The color wasn’t the bluish white of snow and ice, but rather a radiant, pink-hued ivory."

My last day began with a view of the salar again — not under the sun’s glare this time, but under the gentle cloak of sunrise. After waking up at 4:30 a.m., Torres and I drove into the middle of the salt flat in the dark and got out, wrapped in thick clothing against the freezing temperatures. Our hot breaths were like cloudbursts in the thin Andean air. We were the only souls for miles around.

Slowly the stars dimmed and the moon plunged. What followed was an operatic daybreak. The overture came in tangerines and indigos, reaching a crescendo of shimmering gold that refracted in the bone-white salt crystals. The ending was all pastels: powder blues and pinks that reminded me of the flamingos back at Laguna Colorada. Torres set out a breakfast spread — coca-leaf tea, fruits, and pastries — and we sat in camp chairs on the salar, watching as our early-morning shadows stretched across the roof of the world.

A version of this story first appeared in the May 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Reach For the Sky."

explora.com; seven-night private itineraries on the Travesía Atacama-Uyuni route from $8,400 per person, all-inclusive.

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.