I Went Through a Clinical Study to See if I Had Dementia

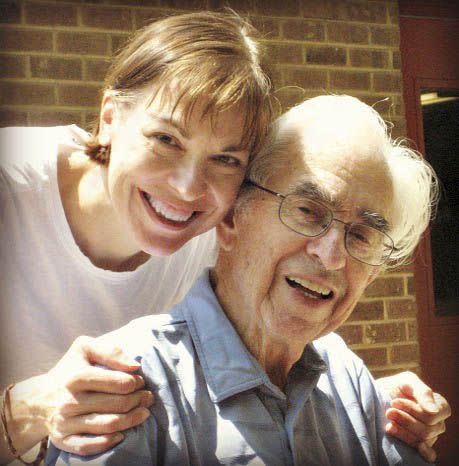

My gram had been my third parent, a fixture at every birthday party and big life event. In her 80s, she forgot me. So did my once independent mother-in-law, who began to get lost driving and would “see” grizzlies in her suburban backyard. Dementia stole three other close relatives as well.

Like many in families touched by a chronic disease, I’ve done what I can to help. I’ve learned as much as I can about Alzheimer’s and how to provide good care. It never feels like enough. They keep getting worse. Day after day left me feeling sad, worried, angry - and helpless. So you’d think I’d have jumped to sign up when my doctor’s colleague suggested that I might qualify for a clinical study she was conducting to help figure out why women account for two-thirds of Alzheimer’s cases. After all, three of those five beloved family members were women. And I was worried about my aging brain.

Instead, I balked, at least at first.

Nervous, But Curious

Neuroscientist Lisa Mosconi, Ph.D., contacted me because I was a healthy patient at Weill Cornell Medicine’s Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic in New York City, where she is associate director. Worried because my family history meant I was more prone to the disease, I’d gone to the clinic to assess my risk and get lifestyle and medical recommendations for lowering my odds. Mosconi told me my age put me in the right window (40 to 65) for her new National Institutes of Health-funded trial exploring female-specific risk factors. In earlier studies, she’d shown that the transition to menopause was associated with brain changes linked to Alzheimer’s. Now her team was hoping to figure out likely treatments as well as the best time to intervene.

For answers, the researchers needed to look inside the brains of more than 100 women - perimenopausal and postmenopausal ones as well as those with no signs of menopause. They hoped it would reveal the impact of hormonal activity and hormone replacement therapy, what biological factors were driving menopausal brain changes, and more. “The best news is that our approach to treatment will be based on information from our patients’ actual brains rather than some old-fashioned preconceived notions around women’s health,” Mosconi explained. “So, um, exactly what would I have to do?” I asked. I didn’t mention that I am a medical weenie who postpones her routine checkups. (I’m so afraid of needles, I gave birth without an epidural - four times! - in order to avoid the injection.)

I’d already had the cognitive and genetic testing required as part of my assessments at the clinic. Mosconi told me I’d undergo a blood draw (uh-oh) to check my hormones and then have three brain scans: a 45-minute MRI for pictures of my brain structures and two PET scans to show how my brain’s metabolism was working and reveal whether I had any amyloid plaques (amyloid, a substance considered the first sign of Alzheimer’s, begins to collect many years before symptoms appear). Then I’d be questioned about lifestyle and diet. The scans and testing would be repeated at intervals a year or more apart to track changes over time.

When she mentioned that there were hardly any studies that looked at women’s brains in midlife, I finally agreed to be screened to see if I qualified. A week later, Hollie Hristov, Mosconi’s nurse practitioner, called with medical-history questions and invited mine (“So, what happens in a brain scan?”). I was a good fit. She sent a 14-page consent form recapping the study’s procedures, and on it I read: “Knowledge gained from your participation may benefit others.” Like my three daughters, I couldn’t help thinking. Brain science was moving so fast, maybe these insights would help spare me so my girls would never need to care for their mom as I had for my relatives or suffer dementia themselves.

OK, then.

The Study Begins

On the day of my scans, I arrived at the imaging center hungry, since I’d had to fast. But I forgot my pangs as a series of white coats ushered me through the process. Every day we hear news reports about study results, but how often do we think about what goes into making them happen?

Not only what, but who - many whos. A nurse logged me in. A technician carefully positioned me in the MRI tube and encouraged me to use the half hour of the scan to nap (I did). Later, a nurse painstakingly adjusted an IV for the PET scan tracers in my “bumpy” vein so a doctor could administer the radiotracer. More white coats watched from behind a glass wall as I twice slid into the PET scanner. Six hours flew past. It was not remotely scary and maybe even fun. I felt like part of a team, though I was pretty sure I was the only one around who’d bombed science and math in school.

All Clear - And Empowered

A week later, Hristov called: My brain scans showed no atrophy or other signs of Alzheimer’s risk. Yes! Given my age, however, those changes could still develop over time - all the more reason for research like this.

Not everyone in the study wants to hear her status, Hristov said. That’s OK by the team; collecting the data is what matters. But to me, knowledge is power; if I already had the early brain changes associated with dementia, I’d be extra motivated to amp up lifestyle habits known to slow disease progression. (Meaning I’d not only finally join that gym, but also use it like mad.) If I hadn’t volunteered, I’d likely never have felt the relief of knowing my brain looked healthy, because at $7,000 and up, the scans are too expensive for routine use, according to Mosconi. I even earned a $150 volunteer fee.

Subject recruitment is a constant challenge for researchers, I’ve learned. Some 250 studies are seeking tens of thousands of participants for research just on Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia. There are similar needs for every disease.

Although I can’t help my relatives, I’m reassured that someday these dogged scientists may be able to prevent dementia cases from developing. Maybe my kids and future grandchildren will be spared - because one medical weenie decided to help.

Take the Brain Health Challenge

A new campaign by Women Against Alzheimer is to aiming to raise awareness and empower women with knowledge about their brains. To get involved with Be Brain Powerful, visit bebrainpowerful.org and take the 30-Day Brain Health Challenge. Every day for a month, you’ll receive a new tip on how to protect your noggin. Follow along on Instagram and Twitter and share your healthy habits using #braingoals.

This story originally appeared in the April 2019 issue of Woman's Day.

('You Might Also Like',)