Is Your Wellness Practice Just a Diet in Disguise?

Wellness is a trap.

When a new acquaintance espouses the benefits of his keto diet over a mutual friend’s birthday dinner, when a woman in a “Spiritual Gangster” tank top suggests I try a juice cleanse for my ailments, when I meet someone at a party whose personality can only be described as “cross fit,” an alarm blares between my ears: Back away from the wellness devotee.

I’ve had to learn to navigate this seemingly innocent but incredibly dangerous cultural terrain. As a woman ten years into eating disorder recovery, as well as a social scientist who explores our relationships to our bodies, I know too well how what looks like a health practice on the surface can, in actuality, be noxious.

And while the behaviors associated with an eating disorder may feel worlds away from your commitment to a vegan diet or fifty squats per day, the line is much more blurred than you might think—and what connects them both is diet culture.

According to Christy Harrison, a registered dietician and host of the popular podcast Food Psych, “Diet culture is a system of beliefs that,” among other aims, “worships thinness and equates it to health and moral virtue,” “promotes weight loss as a means of attaining higher status,” and “demonizes certain ways of eating while elevating others.”

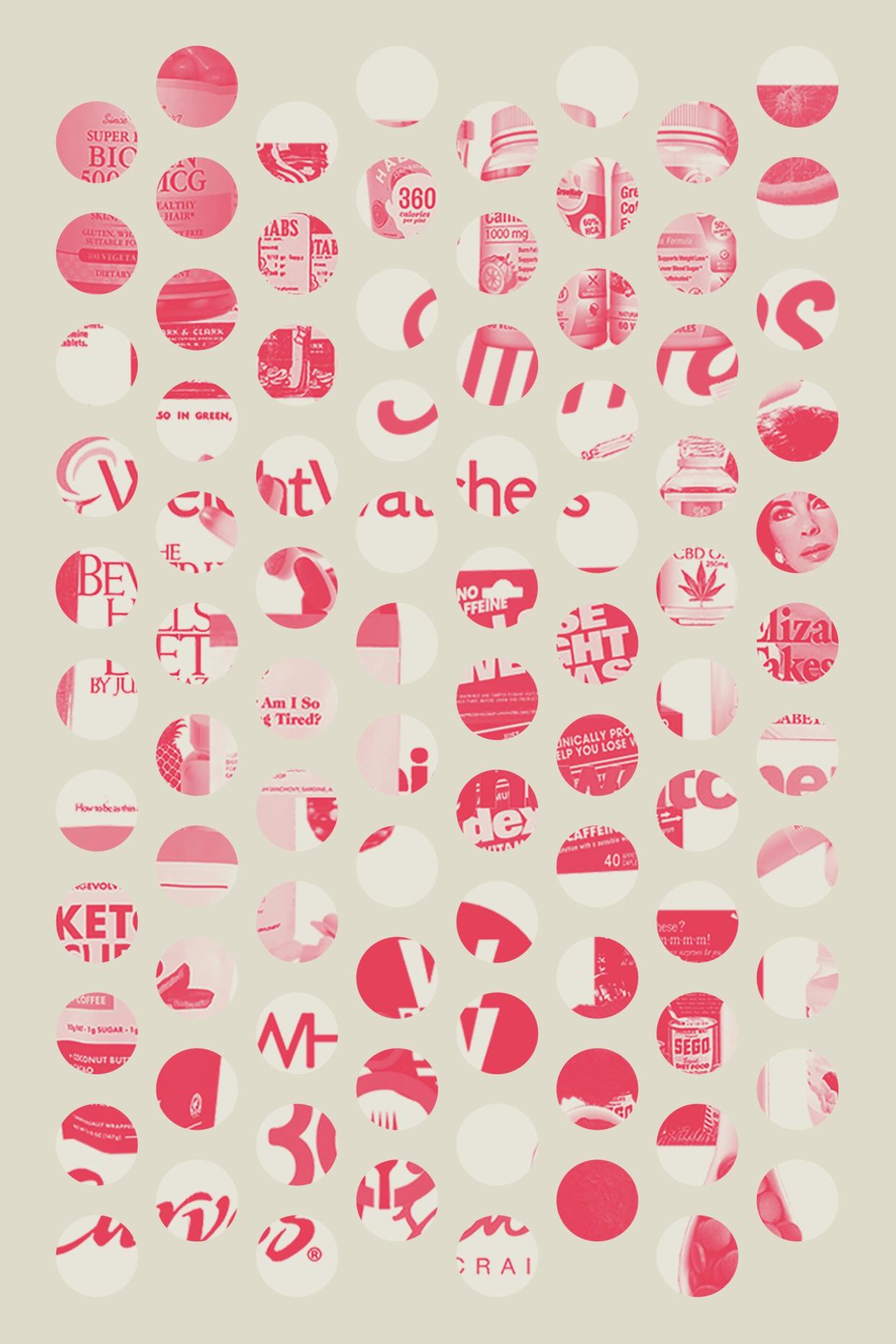

Today we’ve come to associate the concept of dieting with beauty and vanity, so we’ve eschewed the D-word for more noble-sounding “wellness.” From the models displayed in advertisements for supplements to the newfound popularity of company-mandated “corporate wellness” programs to Weight Watchers’ recent rebranding to push “health” over weight-loss, we’re sold this ideal. But whether the standard is based on beauty or health, it’s still diet culture.

Wellness practices—not simple, sensible, health-supportive behaviors but the kinds of commitments and challenges you can hashtag—have exploded in the past decade: The number of people holding gym memberships has almost doubled in the past fifteen years; the number of yoga practitioners in the United States increased by 50 percent, up to 36 million, between 2012 and 2016.

This uptick in wellness practices carries over to our relationship with food, too: In recent years, the ketogenic and Paleolithic diets have gained traction. The goal of the former is to force your body into ketosis, a fat-burning metabolic state. The aim of the latter is to—well—eat like a caveman. Neither is particularly revolutionary. Meanwhile vegetarianism and veganism remain strong (for reasons related to animal welfare and environmentalism, as well as health), and, according to Forbes, “fresh-pressed juices have reportedly boomed into a $3.4 billion industry.”

We’ve taken the vast, complex, beautiful experience of eating and rigidly limited that joy, infusing food with meaning that doesn’t reach past its nutritional value. And while I’m all for people eating in ways that work for them—I, myself, am happily vegetarian—the obsessive restriction of “wellness” can look a lot like an eating disorder. Indeed, orthorexia nervosa, characterized by dietary restriction based on personal interpretation of food purity, might be added to the DSM-6 as a new eating disorder.

We claim that these changes are for our health—that we have merely discovered ways to optimize our bodies based on their evolutionary needs—but ignore how food practices come in waves of fads, too. “It’s funny how our understanding of human evolution…can shift according to which restrictive diet is on-trend that day,” Lindy West writes for The Guardian. Sure, Paleo sounds sensible biologically. But it’s no coincidence that it demonizes carbohydrates—from potatoes to lentils to grains—in a post-Atkins world.

And then there’s the effect that normalizing these new thought and behavior patterns are having on our actual wellness: Exercise addiction afflicts 3 percent of regular gym-goers (and 52 percent of triathletes). Muscle dysmorphia is considered a psychological disorder. Seventy-five percent of women report disordered eating behavior.

Of course, from a biological standpoint, this obsession with health may be related to our very natural fear of death and oblivion. “[C]reating and following diets…is a sort of immortality ritual,” Michelle Allison explains for The Atlantic. “People adhere to a dietary faith in the hope they will be saved. That if they’re good enough, pure enough in their eating, they can keep illness and mortality at bay.”

That mindset makes sense (though it’s based in a harmful fear of disability and aging); it’s hard to fault anyone for wanting more days under the sun. But the pursuit of beauty, really, is no different. The most basic foundation of mate attraction and selection science is that we search for signs of fertility, which are related to a youthful appearance and lack of disease. There are entire industries built around the concept of reversing the signs of aging (skincare, exercise regimens, diets), because aging implies death.

But as Naomi Wolf writes in her then-groundbreaking book The Beauty Myth, “[h]ealth makes good propaganda.” And when pressed to explain how their health practices differ from the beauty routines they claim to not care about, most people fumble, because commitment to either pursuit, in its extreme, is futile (spoiler alert: we are all going to die).

I’m not asking you to quit paleo or boycott your local SoulCycle. I’m simply asking you to question your motives and your impact—to consider what it could mean to eat intuitively instead of restrictively, to move joyfully instead of punishingly, and to rediscover what a relationship with food looks like without guilt or shame.

Ask yourself: Are my choices around food guided by rules that aren’t medically necessary? Could I instead explore what it means to listen to and heed my body’s desires? Is my fitness practice transactional—one in which I exercise so that I’m allowed food? What might it look like to engage in movement from a place of excitement, rather than penance? What are my motivations for how I eat and exercise? Do these routines make me happy in and of themselves, or do I see them as a means to an end? We’re taught to do so many things for the end result. But what if we just did something—ate a cupcake when we craved one, took a passive instead of a strenuous yoga class—because it brought us joy?

It’s possible. In fact, it’s necessary. Because we can’t live full, rich, and (yes) healthy lives if our main motivation is beauty or weight or the fear of death. Until we understand that, we can’t be truly well.