The Way Athletes Dress Is Changing. Can the Olympics Keep Up?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On July 25, the German field-hockey player Nike Lorenz stepped onto the pitch at the Tokyo Olympics wearing what at first appeared to be standard-issue fare: a white tank top, a sports skirt, and a pair of shoes with rubberized soles for extra traction. But where her teammates wore knee-high white socks striped with the colors of the German flag, Lorenz’s were topped with a rainbow-colored band. It might have missed the eyes of most, but Lorenz’s subtle statement in support of LGBTQ+ rights was the result of weeks of speculation and hand-wringing by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the organization that oversees the Games. Eventually, they decided to revise their infamous Rule 50—allowing athletes to engage in acts of political expression on the field while competing, if in terms that still felt wishy-washy—effectively granting Lorenz permission to wear it.

The IOC’s Olympic Charter has been the subject of intense scrutiny for its arcane and often frustratingly vague diktats for decades. First published in 1908, many of its rules are glaringly outdated. Even so, few have prompted the same heated debate as Rule 50, which reads: “No kind of demonstration or political, religious, or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues, or other areas.” In the run-up to this year’s Games, the conversations surrounding the rule grew especially heated, with the IOC releasing a statement in April saying that slogans including “Black Lives Matter” would not be permitted on athletes’ apparel, while words such as peace, respect, solidarity, inclusion, and equality would be.

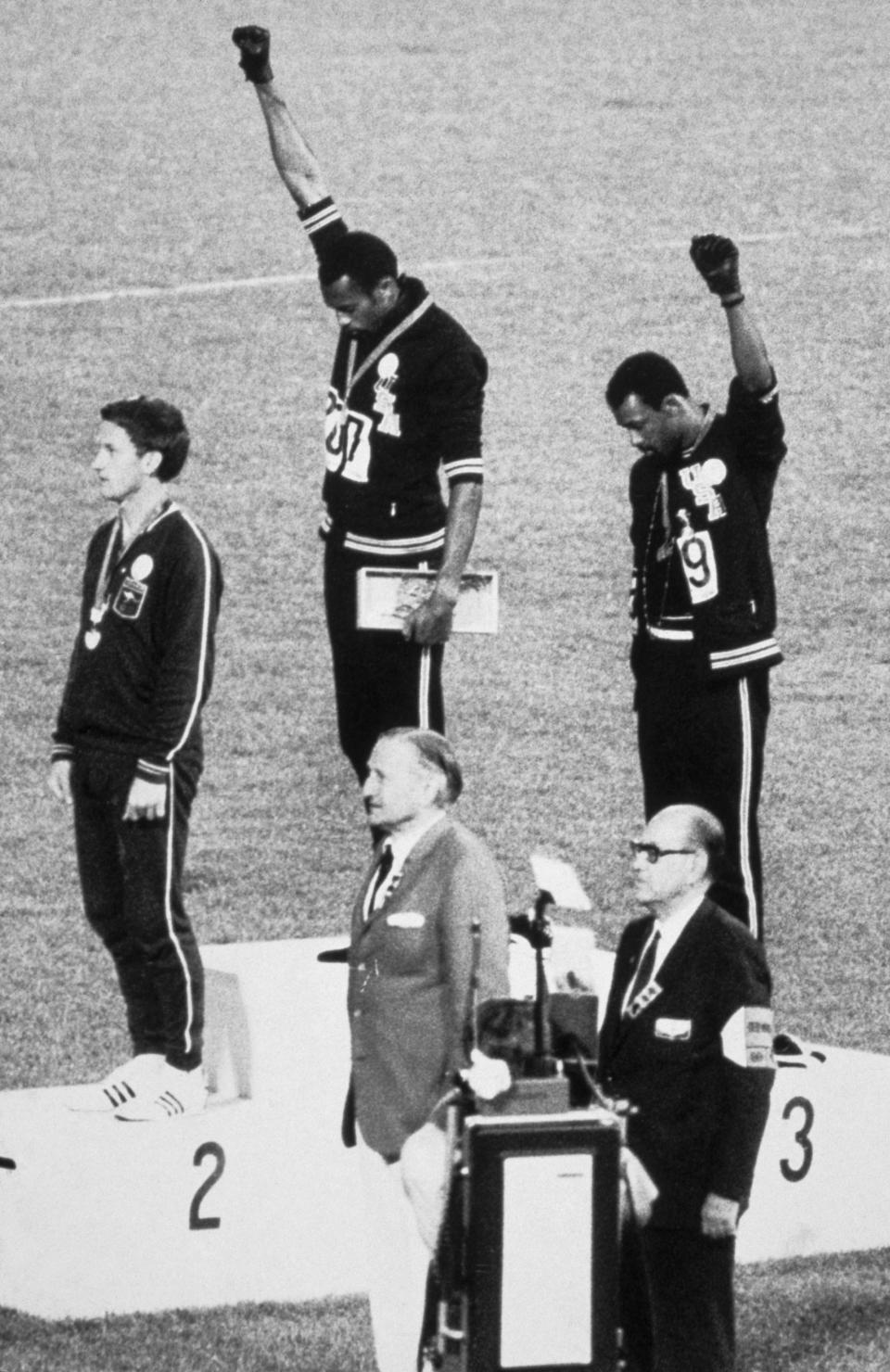

Despite the long history of activism within competitive sports, it’s gained even greater momentum over the past few years—a shift that has arguably been most visible in the U.S. as social media has increased awareness around Black deaths at the hands of police and led to protests, boycotts, and a political firestorm around athletes taking the knee during the national anthem. Even at the Olympic Games, demonstrations are far from a novelty. One of the most powerful examples came at the 1968 Mexico Olympics when, in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination earlier that year, the winning American runners, John Carlos and Tommie Smith, raised glove-clad fists in the Black-power salute. (Before the IOC could even take action, the United States Olympic Committee, or USOC, suspended the athletes from the Games and sent them home within days.)

Olympic Atheletes on Podium

Just what is it that makes clothing such an effective vehicle for protest within sports? “We saw Gwen Berry hold aloft a T-shirt reading ‘activist athlete’ at the Olympic trials recently, so using clothing to send a message was a distinct possibility this year, especially given the increase in attention to fashion that top-flight athletes have been showing in recent years,” says Jules Boykoff, an associate professor of political science at Pacific University in Oregon who has written four books on the relationship between the Olympic Games and political activism. “Clothing that ripples with politics can be an effective way to reach a lot of people quickly with a powerful message for justice.”

As Boykoff points out, given that athletes are most often seen and not heard during their moments of triumph, clothing can be an important tool to express their beliefs during their brief time in the spotlight. While Naomi Osaka’s statements on social media and in interviews about the Black Lives Matter movement were barely remarked upon in the press, when she paid a moving tribute to the victims of police brutality by wearing their names emblazoned face masks during last year’s U.S. Open, it caused a minor media frenzy. “I’m aware that tennis is watched all over the world, and maybe there is someone that doesn’t know Breonna Taylor’s story,” Osaka told reporters at the time. “Maybe they’ll Google it or something. For me, [it’s] just spreading awareness.”

2020 US Open - Day 9

When the news was announced in April that “Black Lives Matter” slogans would be banned from the Olympics, it felt like a particularly egregious and out-of-touch decision, even drawing the ire of Benjamin Crump, a civil-rights attorney who has been nicknamed Black America’s attorney general after representing the families of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor, as well as those poisoned during the Flint water crisis. Upon reading the news—and in particular, the conflation of Black Lives Matter–emblazoned apparel with political speech—Crump was disappointed, if unsurprised.

“When athletes come from marginalized communities of color and express that with clothing that reads ‘Black Lives Matter,’ that is not political speech,” says Crump. “That is a proclamation that we deserve the right to be able to live on this earth and not be killed because of the color of our skin. For the Olympic Committee to confuse that with political speech means that they are far behind the times and on the wrong side of history. That is a humanitarian statement, and I thought the greatest cause of the Olympics was to be one that celebrated our shared humanitarian beliefs.

“Clothing is important, as you don’t get to talk while you run or shoot a basketball or throw a javelin,” he continues. “People readily identify with your apparel, what’s on your jersey, or what’s on your tennis shoes. And so those statements become profound when a young person is trying to find their voice and spread awareness.”

GYMNASTICS-OLY-2020-2021-TOKYO

As well as stifling Black voices, many of the most controversial decisions made by the IOC and various national sports bodies worldwide in the run-up to this year’s Olympics have disproportionately impacted women and, more specifically, women of color. There was the backlash to the shortsighted decision made by FINA, the water-sports world governing body, to ban the wearing of swimming caps specifically designed for Black hair, a rule which remained in place throughout this year’s Olympics. The German gymnastics team caused a stir by wearing full-body unitards instead of bikini-cut leotards this year, pushing back against the sexualization of women within the sport. And ahead of the Paralympics later this month, the Welsh sprinter and long jumper Olivia Breen spoke out after an official at the English Championships rebuked her for wearing briefs, stating that they were “too short” and “inappropriate.” (“Women should not be made to feel self-conscious about what they are wearing when competing but should feel comfortable and at ease,” Breen told the press.)

The growing willingness to address racism and sexism in sports—and how closely entwined they are with the policing of what athletes wear—is reflective of how much more vocal many athletes have become about the causes that matter most to them. “I think it’s fair to say that we are living in what we might call the athlete-empowerment era,” says Boykoff. “The athletes of today are often enmeshed in movements for justice around the world. The general rule of thumb, at least in my mind, is that when you have vibrant social movements in the streets, there is a better chance that you will have moments of athlete activism at the Olympics. Movements scythe space for these moments.”

2020 U.S. Olympic Track & Field Team Trials - Day 9

Yet looking back across this year’s Games, it’s hard not to feel like many potential examples of activism through clothing were stifled due to the IOC’s strictures. Back in April, the organization released a statement saying that it had surveyed 3,500 athletes ahead of the Games, 70% of whom said they did not believe it was appropriate to demonstrate or express their views on the field of play or at official ceremonies. But what of that 30% who did wish to make a statement as they competed? And how many of them represented marginalized people who wanted to make their voices heard?

These questions speak to a vast imbalance of power. Athletes wishing to speak up are subjected to the iron fist of the organizations that govern their sports—inevitably dominated by white, middle-age men—which can lead to disqualification, lengthy bans from play, and a loss of their livelihoods. “The IOC has been resistant to change because it is a fundamentally conservative organization,” says Boykoff. “Its members are out of step with the political zeitgeist on the streets that is demanding justice, whether it is racial justice, gender justice, or economic justice. The IOC is out of step with the times.” But is it worth risking their ire to make a statement?

Thankfully, for some, it still is. The U.S. hammer thrower Gwen Berry, whom Boykoff noted for the “activist athlete” T-shirt she wore during the Olympic trials, took advantage of the revisions to Rule 50 to raise her fist in protest before taking her shot last week. (After making the same gesture at the Pan American Games in 2019 after winning the gold medal, Berry was placed on a yearlong probation by the USOC.) The Black, gay U.S. shot-putter Raven Saunders made the first podium demonstration after winning a silver medal, crossing her arms in an X to represent “the intersection of where all people who are oppressed meet.” The 18-year-old Costa Rican gymnast Luciana Alvarado even found a way to incorporate a raised fist and a kneel into her floor routine in honor of the Black Lives Matter movement. Still, given the significant attention devoted to the possibility of political controversies during this year’s Games, the actual examples remained few and far between, arguably confirming that the IOC still wields an outsized amount of power on athletes’ political expression.

Athletics - Olympics: Day 9

While some remain hopeful for change, it feels like the real test for the IOC is yet to come. The beleaguered sports body has been facing widespread criticism for pressing ahead with this year’s events during a new wave of COVID-19 cases in Japan, its extreme corporatization and alleged greed, and its willingness to become bedfellows with regimes with notoriously poor human rights records. Next year the Winter Olympics will be held in Beijing, and given China’s track record with freedom of speech—as well as the numerous human rights injustices that have plagued Xi Jinping’s regime, from censorship to religious repression in Xinjiang and Tibet and the crackdowns on pro-democracy protestors in Hong Kong—the IOC’s stated belief in political neutrality may well be tested further.

That sartorial displays of support for political causes or human rights movements should send the IOC into a tailspin, however, is a problem of the group’s own making. If it truly believed that bringing athletes from around the globe together could make the world a better place, it would support and applaud those speaking up about human rights issues, not condemn them. And at the end of the day, the reason millions of viewers tune in for the Olympics is not to see the flashy new stadiums or the rampant advertising from corporate sponsors. It’s to see international athletes competing at the top of their games and to witness the highs and lows of the two weeks that they’ve spent years preparing for. It’s only fair that these athletes should be allowed room for self-expression—and what greater form of individual self-expression is there than what we wear?

Originally Appeared on Vogue