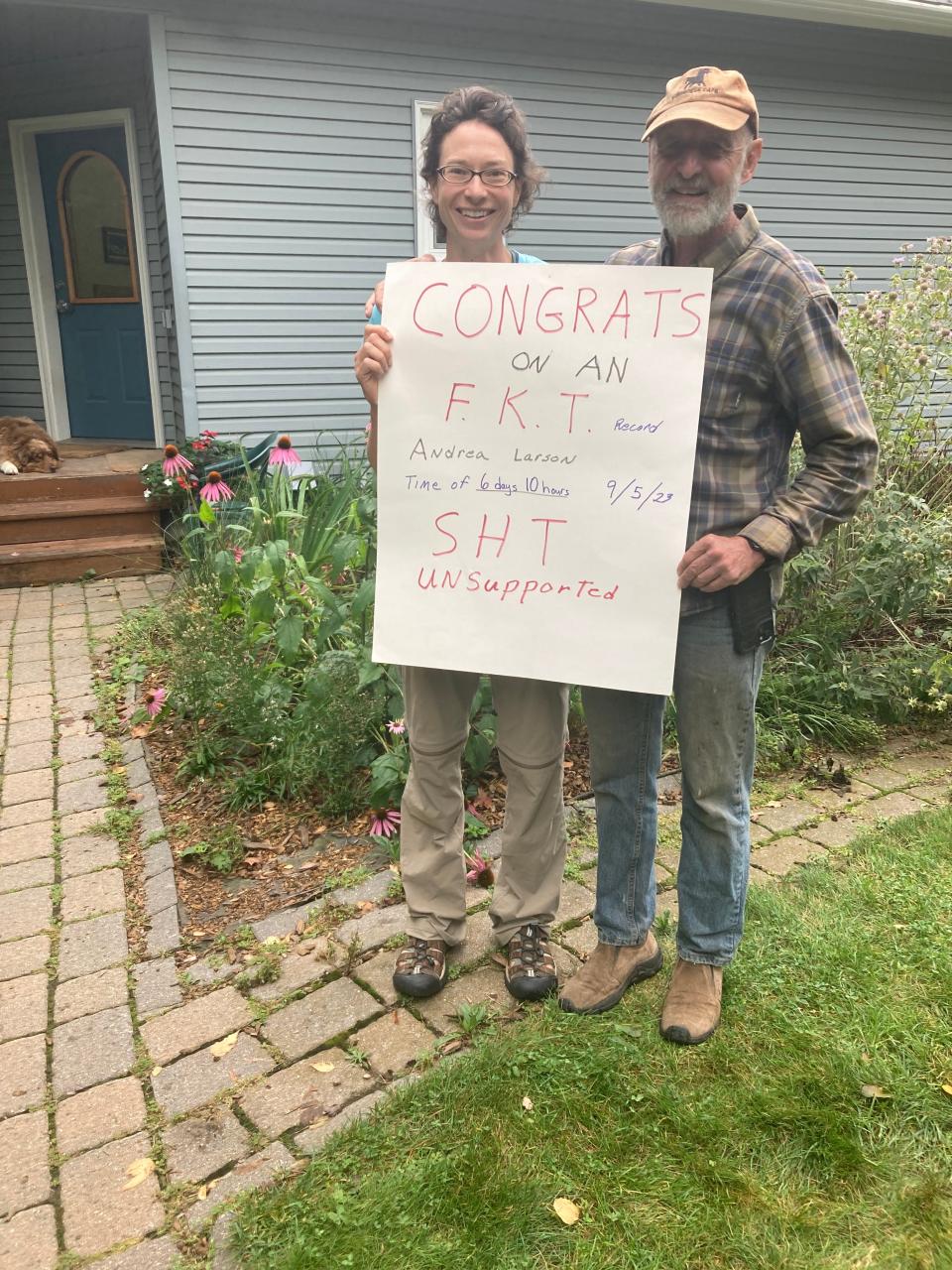

Wausau's Andrea Larson sets FKT speed record on the 310-mile Superior Hiking Trail

RIB MOUNTAIN — She reckoned she had about a 50-50 chance to set the women's speed record for running the Superior Hiking Trail in northern Minnesota.

If she didn't set a record, or even if she didn't complete the 310-mile trek along Lake Superior's North Shore, Andrea Larson of Rib Mountain figured she would learn valuable lessons about the limits of endurance and have spent time in a beautiful area.

She did all that and more. By completing the route in 6 days, 9 hours and 52 minutes between Aug. 30 and Sept. 5, the 38-year-old ultrarunner set an FKT, or "fastest known time," for completing the Superior Hiking Trail, eclipsing the previous female unsupported record by nearly 17 hours. In doing so, the mother of three persevered through heat, rugged terrain and the tricks that her own mind played on her.

And she did it all without any outside help.

FTKs are speed records for hiking, running, cycling and even paddling routes. They are most often done solo or with a small team of athletes. This is a niche genre of endurance sports, although a growing one. FTKs have their own rules and expectations. Competitors use GPS coordinates to mark their times and progress and to prove their accomplishments.

Participants can choose to go for FTKs fully supported, meaning they can have a team of helpers shuttle in food and water along the way, or even get pacing help while on the trail. There is a self-supported category, in which participants cache supplies in locations along the trail. And there is the unsupported category that Larson completed her trek in, in which runners have to carry everything they need with them throughout their effort.

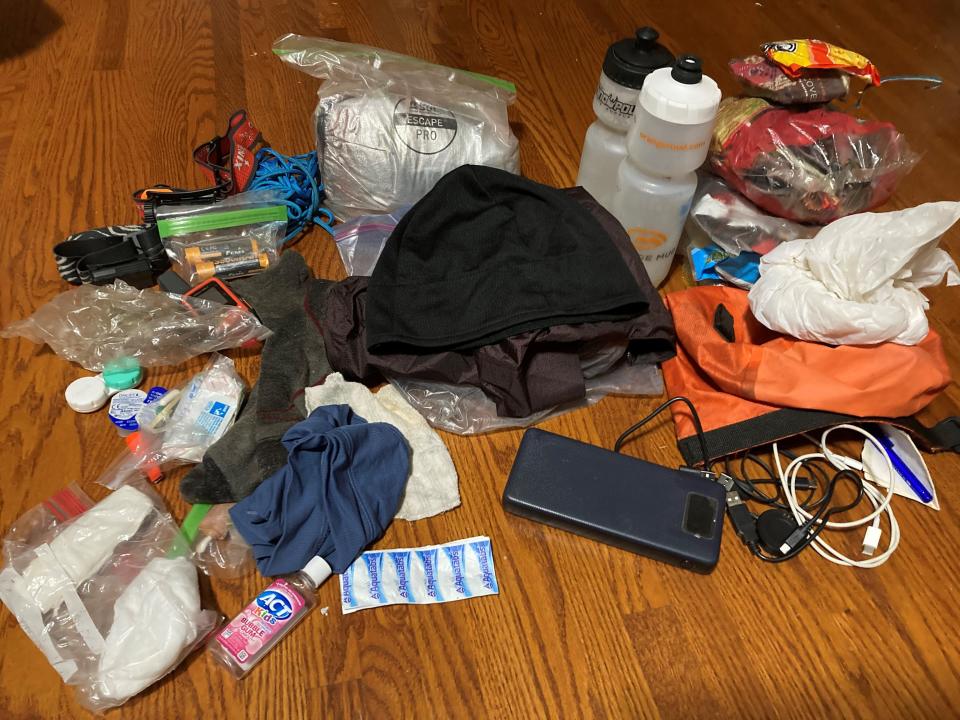

Larson originally planned to go self-supported. But a few days before she planned to set out, she changed her mind. The logistics of dropping supplies along the trail was cumbersome. So she decided to pack everything she would need in a backpack about the size of two loaves of bread and in the pockets of her running pants.

In doing so, Larson was breaking a cardinal rule in endurance sports: Don't try anything new when striving for a goal.

"When I switched from self-supported to unsupported, my chances went way below 50-50," Larson said.

She set out at the end of August, she said, with low expectations and "a child-like mentality of, I'm not going to let it get in my head how daunting this is. ... I'm going to learn a lot from this experience. And that was my primary goal."

So just what does it take to push the boundaries of endurance and set a record? A million things. But Larson's victory on the Superior Hiking Trail rests on a foundation of five training pillars.

RELATED: Coree Woltering sets new Ice Age Trail record, running 1,200 miles in under 22 days

Setting an FKT takes motivation

Larson had an active and athletic childhood growing up just outside Marathon City.

"We had a creek behind our house when I was growing up, and an old pasture with apple trees," she said. "So I've always enjoyed playing in the woods."

She said that trail running and the fast hiking she did on the Superior Hiking Trail and other ultra events she's participated in through the years is an extension of that childhood playtime.

"Now I call what I do 'frolicking in the woods.' I would do it all the time if I had no time constraints," she said.

Larson was one of less than a handful of girls to go out for Marathon's new cross-country team in high school, she said, because it was "running in the woods." She continued to compete as she studied engineering at Michigan Technological University in Houghton, Michigan, running in the fall and spring, and Nordic skiing in the winter.

"I still love running more than ever," Larson said. "It might have changed in some respects. It's more of an adventure now."

Larson is the executive director of IRONBULL, a Wausau-based nonprofit organization that promotes outdoor adventure sports such as gravel bike races and adventure challenges that mix paddling, cycling, trail running and orienteering.

The motto of IRONBULL is "Find Your Tough." That can mean vastly different things for different people, Larson said. She hopes that her FKT inspires everyone to get out and be more active, no matter their fitness level.

Setting an FKT takes experience

In March, Larson competed in the Barkley Marathons, an idiosyncratic ultra known as "the race that eats its young" that requires runners to finish five loops of a 20-mile course within 60 hours. The course is unmarked (competitors have to find their own way to several checkpoints) and rugged. It is designed to make finishing near impossible. Larson did not finish. But she learned a lot about what it takes to do something really, really difficult.

It takes a special kind of endurance athlete to even gain entry to Barkley Marathons, and it requires an uncommon resume of ultrarunning accomplishments. Larson has never done a traditional marathon, but she has a long list of ultra completions.

Some highlights include being the first woman to finish the 50-kilometer Barkley Fall Classic in September 2022. She finished third overall. She also finished sixth overall (second woman) in a 100-mile race in the Kettle Moraine in June 2022.

None of this happened overnight. It's been a long and steady build for Larson to get to the point where her body can handle the hours and days of running and hiking.

Setting an FKT takes superb fitness

Before competing in the Barkley Marathons, Larson "Everested" Rib Mountain by running up and down the hill 71 times. Everesting is repeating a climb until one reaches the equivalent height of Mount Everest, 29,029 feet. Larson covered nearly 60 miles in the 15-hour effort.

The accomplishment shows Larson's strength and endurance, but it's the consistent training over time that allows her to put in these superhuman efforts.

She typically trains using hours rather than miles, she said. In addition to trail running (she usually avoids roads), Larson logs time biking, skiing and general hiking and bushwhacking. She lives near Rib Mountain and often runs up and down the slopes. There are also steep hills right outside her door where she'll do off-road hill repeats.

Larson is a busy mother, so she finds ways to fit working out into daily life. Biking 13 miles with her children to swim lessons and back? Check. Running 10 miles home after church? Yep.

She took specific training trips to northern Minnesota before making the FKT attempt. The scouting trips doubled as family camping outings, Larson said, so her kids played in Lake Superior while she ran, and her husband would pick her up at predetermined meeting spots.

Larson figured she ran about half of the trail before attempting the FKT.

Setting an FKT takes smarts

Larson took a calculated risk when she chose to do the FKT attempt unsupported.

She used a pack about the size of an elementary student's backpack. She and her husband, also an engineer, zip-tied bags of freeze-dried food to the outside of the pack. She brought just a few items of clothing: a top, running shorts, pants. She left a jacket behind, trusting weather reports that called for hot conditions.

She knew it would be impossible to take in as many calories as she would burn throughout the trek, so she started out the first day eating almost constantly. But her mouth started to develop sores, so she decided to eat more in clumps, say on an hourly basis, and brush and floss her teeth four times a day instead of two.

She also experienced hallucinations. At one point, she believed that the friend and mentor who was going to pick her up at the end of the trail texted her to say he couldn't make it and made other arrangements. She was surprised to see him when he did indeed show up.

Through it all, Larson stayed in control, knowing her strengths and limitations. Her fastest miles took about 12 minutes, a slow jog for seasoned runners. Her heart rate throughout was never above 140, 150 beats per minute, a moderate effort for a trained athlete.

One of Larson's strategies was to stay on the move as much as possible, even if it was slowly. That meant she didn't sleep much. She carried a light-weight bivy sack for protection, and used a plastic garbage bag as a ground cover. She used a small, lightweight pad from her backpack as a sleeping pad.

Larson didn't sleep at all the first night. After that, she would sleep two or three hours a day, most often at night. Later in the trip, when she was struggling with heat, she attempted to sleep in a stream, propped up between rocks to prevent herself from drowning if she did fall asleep deeply. She didn't; a hiking family came along, and she sat up so that they wouldn't think she had died, she joked in an online blog outlining her FKT experience.

The heat and lack of water in drought conditions were the biggest obstacles she faced, she said. Managing the heat meant taking the time to soak in streams to keep her body temperature down. That slowed her progress, she said, but she never felt close to stopping her attempt.

At one point, she worried that she might run out of water, after coming across a dry creek. It wasn't anywhere near serious enough for her to consider quitting, but she did make internal plans to urinate in her water bottle. She knows how that sounds, "but I didn't have to do it!" she said, because she found a water source.

Larson also had the common problems that ultramarathoners face, such as aches and pains and blisters on her feet.

She also was able to maintain a good mental space, she said. She enjoyed the time being on her own. She found the diverse landscape of northern Minnesota along the shore of Lake Superior to be interesting and gorgeous.

And most of her thoughts were focused on what she needed to do to finish.

"I was very much in a race mode," Larson said. "I would say for anything of this magnitude, it is so much mental. A lot of times, our minds stop us before our bodies."

Setting an FKT takes luck

Any one thing could have derailed Larson's attempt. A wrong step or a weather event could have sent her home.

She knew that leaving a jacket behind was a risky endeavor, especially with the erratic weather that can come to the areas along Lake Superior.

"If you want to go fast, you have to go as light as possible. And there are risks with that. It could end your day," Larson said.

Now, as she looks back on the effort, she feels amazed, grateful and proud.

"It was so empowering," Larson said. "I found out I could not only survive on my own, I could cover 310 miles. It seemed absolutely daunting, but it's that one-step-at-a-time approach. I can keep going."

Keith Uhlig is a regional features reporter for USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin based in Wausau. Contact him at 715-845-0651 or kuhlig@gannett.com. Follow him at @UhligK on X, formerly Twitter, and Instagram or on Facebook.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Ultrarunner Andrea Larson sets FKT on Superior Hiking Trail