We Watched “Grizzly Man” With a Bear Biologist. It Got Weird.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This article originally appeared on Backpacker

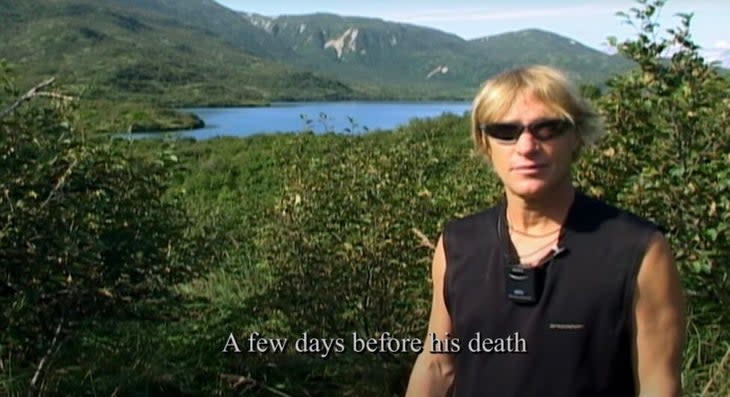

Every time someone does something foolish around a bear, the internet has two words for them: Grizzly Man. It's hard to think of a backpacker who isn't familiar with Werner Herzog's critically acclaimed documentary or its idiosyncratic subject Timothy Treadwell. When the movie came out in 2005, it was a Sundance Film Festival hit, but even before that, Treadwell was a well-known figure for both his time living among and documenting the brown bears of Katmai National Park and the unpleasant way it ended.

However, there's one backpacker who has remained more or less oblivious to Grizzly Man's story: me. I credit that to being 6 years old at the time of its premiere and likely more interested in the Berenstain Bears than documentaries about the cruelty of nature. Nearly 20 years later, it just never made it to the top of my queue, and I found myself in a staff meeting admitting that I, a Backpacker editor, had never seen Grizzly Man.

I decided that if I was going to watch it, I had to do it right. I enlisted the help of Wesley Larson, a wildlife biologist and host of Tooth and Claw, a podcast that examines human-wildlife conflict and the lessons we can learn from it. Larson has worked with everything from black bears to polar bears, and he joined me for a watch party to explain what Treadwell did wrong (and, sometimes, right) throughout his time in Katmai.

Here's an edited version of our conversation.

Wes: There are multiple bears in the shot: You've got a female with cubs; you’ve got what looks like a couple of males. In coastal Alaska or coastal British Columbia, where you have these really great food resources, you see a lot of bears in the same places. Because they’re so used to being around other bears, they’re not nearly as aggressive or nearly as territorial as bears in Yellowstone or Glacier might be, because there’s so much food, and that food has allowed them to be at such high densities. They treat us like they treat other bears in places like this.

They are really tolerant of humans because they’re also tolerant of other bears. That's why Timothy was able to get so close. That’s why when you see people in Katmai or Brooks Falls, they have bears walking right next to them. If you have the same exact bear in Yellowstone or Glacier, it’s the same animal, but it’s going to act much more aggressively because it has to defend its resources and its territory and everything from other animals. These guys don’t really have to do that. They’re much more docile and tolerant of human presence.

"They use people almost as babysitters"

Emma: How close is that? That’s not zoom, right?

Wes: Right. It's because these bears are okay with people being around. There are even some anecdotal observations of female grizzlies that will leave their cubs with people observing them and go fishing. They use people almost as babysitters for their cubs, because they have become so tolerant of other bears and people. He’s way too close, though. It's definitely not a situation you should ever find yourself in unless you’re with a guide.

Emma: That's a lot of trust in the animals.

"It's flirting with disaster"

Wes: As bear biologists, we often say that you don’t want to let the animals make the decision on how that interaction is going to go. That's why having a deterrent is so important. You want bear spray, because that gives you the power to decide how that interaction is going to end up, and gives the animal that power, which Timothy did in all of these circumstances. I don’t personally feel comfortable not having control over the interaction.

Emma: Do you think that it’s inappropriate that Timothy was seeing these signs of aggression and ignoring them?

Wes: It’s flirting with disaster. I don’t know if I would say it’s inappropriate. He’s stressing the animals out. He’s making them have to communicate that over and over and over again. If you’re constantly having that kind of interaction with bears--even if it’s always just the bear telling you that it’s upset and never initiates a mauling or anything like that-- it’s the bears telling you something, and you’re not listening.

He sees that as, "I’m proving to the bear that I’m dominant." Sooner or later, even if it takes years, you’re going to meet a bear that decides that it wants to engage, that it doesn’t want to leave it at that. It wants to take it a step further.

"Timothy thought he was the dominant bear in the ecosystem"

Wes: I’ve spent a few days flying around Kodiak with Willy [Fulton], and we talked about Timothy and bears the whole time. He’s a really cool guy and a great pilot, so I was lucky to spend some time with him.

He mentioned he always had a bad feeling about that bear that he and a lot of people think was responsible. A number of people think that it was a different bear that killed him, and this bear pushed that smaller bear off of the carcasses and started feeding, which happens a lot, especially in a dense population of grizzly bears. Just because this bear they killed had Timothy’s and Amy’s remains inside of it doesn’t mean it’s the responsible bear. It would be a bear you would still probably want removed from the population because it has fed on a person, but there is some debate there.

Emma: Where do you fall in that debate?

Wes: I tend to believe it was a different bear. My advisor was working in Katmai at the time, he was really close to all of this, and that was his opinion. I trust him because he was there and he knows bears really well.

Wes: Timothy thought he was the dominant bear in the ecosystem. I think he was past the point of accepting any input on that. I think he had convinced himself that they would never hurt him, and he was untouchable.

Emma: Sounds like he had a god complex.

"I’m sure his last his last feelings were, 'Oh I fucked up.'"

Emma: How is Timothy not going crazy? I mean, he kind of is--he’s all alone. At least he has the unknown viewer to talk to.

Wes: It’s like that show "Alone" where they talk to the camera all the time, and that almost becomes a stand-in for another person. But, Willy checked in and out and dropped off supplies. And he’s in Katmai; he’s in a place where there is a fair amount of tourism. It's not like he never had contact with people. He did have contact with park officials, and my advisor wrote letters back and forth with him. I think like a lot of things in his life, he tried to make it seem more romantic than it actually was.

Emma: So do you think, as he was dying, he was happy about it because he was kind of a martyr?

Wes: No. There’s audio recording of him dying. My advisor listened to it. I’ve never listened to it, but it’s 15 minutes of him being dismantled by a bear. You can hear his arm being separated from his body in it. It’s the worst possible way to go.

There’s no way for a split second in that experience he was like, "Yes, finally, this is how I wanted to go." It is a terrible, awful, violent way to go, and I’m sure his last his last feelings were, "Oh I fucked up." Not like, "Oh this is great; I’m dying the way I wanted." It’s like, "I need to get out of this experience as quickly as possible."

Wes: You can see there’s a big difference between the two environments where he camped. With these bears in Hallo Bay, it’s very open coastal grass. You have the ability for the bears to see you approaching. They have this warning distance where they get to recognize, "Okay, this is Timothy." They know him, they know his presence, they know what’s happening.

Then in an environment like in the Grizzly Maze, there are really thick alders and this dense habitat where it’s much easier to surprise a bear. They have a lot less time to decide if you're friend or foe, if you're food or not. It’s a much more complicated environment to be around an animal like a grizzly bear. I do think that does play a factor in what ultimately happened to him. This dense, enclosed environment where they have to make much quicker decisions than they would in a place like Hallo Bay.

“He was doing no good by being there."

Emma: Do you think that [Timothy] was as effective in his mission as he wanted to be?

Wes: I guess, in a weird way because Werner Herzog made a documentary about him, [he] was. I think a large number of people now see that grizzly bears aren’t bloodthirsty mindless killers, or they do have behaviors that are somewhat predictable to where people can even coexist with them.

On the other hand, his mission was a failure in that he was trying to protect those specific bears, and he got at least two of them killed. They killed two of these bears that were feeding on him, and who knows how many other bears became so habituated to humans that they also had to be killed because of problem behavior. I do think he was very misguided.

Timothy thought he was protecting these bears. These are bears in Katmai National Park; they have access to salmon streams, and they have access to all these great coastal resources. These are literally some of the most protected bears in the world with the healthiest populations. This is, to me, one of the most delusional things that he had going for him.

This might sound a little harsh, but to me, Timothy was all about Timothy. He wanted to be close to the bears, he wanted to have this access to them and have this personal relationship with them. He was doing no good by being there. It's really fascinating to hear throughout the documentary him saying things like, "I’m here to protect them. They need me as a protector," because that’s completely off base.

Emma: It doesn't sound like they needed him as much as he needed them.

"They died in a really violent, horrible way.”

Wes: I respect the passion he has for these animals. It’s hard to work around an animal as charismatic as a grizzly bear and not want to devote your life to them. The channel he picked to do that was really unhealthy and self-serving.

This is an animal that had a very healthy population in a protected area that didn’t need any interference. That’s why these park personnel weren’t interfering with them, because they were existing in a natural state. For whatever reason, he thought he needed to be there to protect them, and he absolutely was unnecessary. I think the way he chose to [protect them] was very harmful and ultimately cost him his life and the life of an essentially innocent bystander. They died in a really violent, horrible way.

When you’re eaten by a bear, they’re very different from other predators, in that a lion or a tiger or a big cat is going to dispatch their prey and bite through the windpipe or do something to kill it, so they can then drag it somewhere to consume it safely. A bear doesn’t do that; a bear will literally sit on you and eat you. Often these people die by bleeding out, and it takes a long time. It’s 10 to 15 minutes of this bear sitting on you eating you alive, not ripping out necessary organs or something to kill you. Sometimes you luck out, and the bear kills you quickly. In his case, that wasn’t what happened.

"If you need to go live with an animal in the wild, get a dog."

Emma: It seems like he idealized everything about his situation before he was killed, including the risks. "If that’s how I die, that’s how I want to die" seems like a delusional way of thinking.

Wes: When I started my journey in bear biology, I always thought, "I hope I’m killed by a bear at some point." The more I’ve learned about it, especially doing Tooth and Claw and learning about how terrible of a way it is to go, that is absolutely not how I want to die. It is the last way I want to die.

If you’re around bears, have a deterrent with you, even if they’re black bears because it gives you so much more power in those interactions. There’s no reason not to have that extra safety with you. It’s like driving in a car without a seatbelt. It’s right there; it’s easy to use. If you decide not to have that seatbelt, at that point, you’re giving up a lot of control.

Sometimes people ask me, "What do you do in a bear encounter?" And I always say, "Get your bear spray out, and get it ready." They’re like, "What if I don’t have bear spray?" Well, you’re already sacrificing your control of that situation. You’re not wearing your seatbelt, you’re deciding that you’re going to take a bigger risk than you need to.

Also, if you need to go live with an animal in the wild, get a dog, get a different hobby. Go talk to a therapist and do something else, because I can almost guarantee you’re not going to be doing any good unless you’re a biologist doing some sort of study or you’ve been hired to do that. You're doing some harm.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.