Watch This Prosthetic Hand Win an Arm Wrestling Match

The energy inside the University of Illinois’s State Farm Center was electric last August as Dan St. Pierre made his way through the arena’s arteries and toward center court. As a U.S. Paratriathlon National Champion, St. Pierre is no stranger to pushing his body to its limits. But as he shrugged off an orange wrestling robe and squared up against his opponent at center court, St. Pierre braced himself for an entirely new challenge: winning an arm-wrestling match.

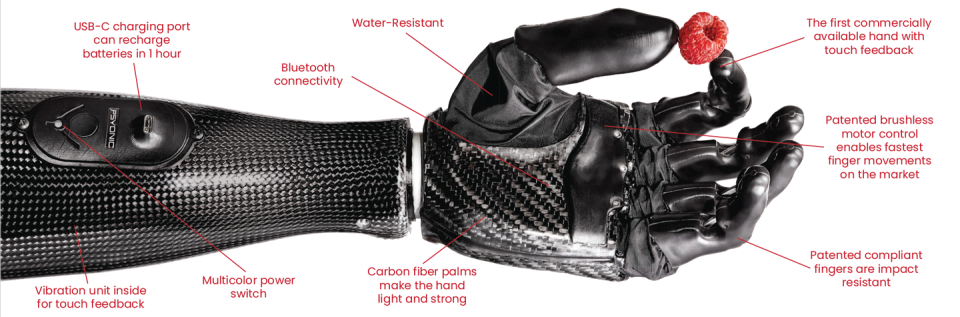

Unlike the other athletic competitions of St. Pierre’s career, this match was not for medals or prizes, but instead was meant to test the strength of a new kind of bionic prosthesis, called the “Ability Hand,” designed by medtech company Psyonic. Creating a prosthesis robust enough to slam down its opponent’s hand in an arm-wrestling match is just one part of a long-term vision that St. Pierre’s opponent and Psyonic CEO, Aadeel Akhtar, has been working toward for decades.

“Aadeel asked me to push the hand to the max and the durability is unmatched. From lifting weights to yard work, this hand holds up,” St. Pierre tells Popular Mechanics. “When I received my first myoelectric hand in 2009, it came with the disclaimer ‘Don’t bump it, don’t be too rough, don’t get it wet, don’t get it dirty.’ At that point, it’s not functional anymore, and it’s just aesthetic … the Ability Hand is changing that narrative.”

In the last decade, prostheses have come a long way in terms of how they interact with and fit to a user’s body. However, as Akhtar was completing his master’s and then Ph.D. work on the topic, he became increasingly concerned about how the price point of these prostheses—which could cost as much as $100,000 and may not be covered by health insurance—was limiting their use. Not to mention, these price points don’t necessarily equate to durable products, Akhtar says.

“[Prostheses were] breaking within months of people using them,” Akhtar tells Popular Mechanics. “It’s not because they were doing anything crazy with them, it’s because they would accidentally hit their hand against the side of a table. And because the fingers were made out of rigid materials, they would just snap at those joints.”

Driving Down the Cost

Driven by these observations, Akhtar founded Psyonic in 2015 to focus on building a robust prosthesis with a more reasonable price point. To be exact, the prosthesis costs between $10,000 to $20,000. This price does not include extra fees, like fitting and testing the prosthesis, but in total, Medicare can cover $30,000 to $50,000 of the final price. After years of work, the Ability Hand was released in September 2021 and is now marketed as the “world’s fastest and first touch-sensitive bionic hand.”

Psyonic is far from the only company innovating in this space; its peers include companies like Atom Limbs, Unlimited Tomorrow, and Open Bionics. But what sets the Ability Hand apart from its competitors is its unique approach to strength and functionality, Akhtar says.

“We had to kind of think outside the box with how we could still leverage things like 3D-printing and low-cost manufacturing, but make this thing actually be more robust,” Akhtar says.

For the fingers, he says that they learned to 3D-print finger molds and fill them with compliant materials like silicon and rubber instead of more traditional injection-molded plastics and machined steel. Meanwhile, the palm of the Ability Hand is 3D-printed and then overlaid with carbon fiber to be extremely light.

“The Ability Hand weighs 490 to 500 grams (roughly 1.08 to 1.10 pounds), and an average adult human hand is around 510 to 520 grams (roughly 1.12 to 1.15 pounds),” Akhtar says.

A More “Human” Bionic Hand

With the Ability Hand, Akhtar says he wants to design something that cannot just meet, but exceed, users’ expectations of what a prosthetic limb can do. That’s where designing functionality for arm wrestling or even agile bottle-flipping comes into play. In preparation for his match against St. Pierre, Akhtar and the Psyonic team spent weeks testing and perfecting the strength of the Ability Hand’s wrist and how it responded to kinetic forces, like 30 pounds of transverse force (or force applied along a horizontal plane) from an opponent’s hand.

While a piece of the equipment used to test the hand—a load-testing set-up designed to measure total force used when arm-wrestling—broke under pressure, Akthar says the Ability Hand came through unscathed. When match time arrived, Akhtar didn’t stand a chance against St. Pierre and the Ability Hand.

Paul Marasco is a researcher and head of the Laboratory for Bionic Integration at the Cleveland Clinic. At his lab, Marasco works on developing neural-machine interfaces for prostheses like the Ability Hand to improve how users experience touch from their synthetic limbs.

Marasco says there are two types of prosthetic interfaces: mechatronic interfaces driven by electric signals from muscle contraction, and neural-machine interfaces driven by a user’s thoughts. Right now, the Ability Hand falls into the former category.

While this mechatronic interface may be comparatively less sophisticated than computer-machine interfaces being trialed at universities, Marasco says that having more robust mechatronic interfaces like the Ability Hand play an important role in advancing other forms of prosthetic controls, as well.

“It’s a nice device and it seems strong and looks really functional,” Marasco says. “I think the more opportunities that we have for robust, strong hands that are multi-functional, the more we can utilize them as control interfaces.”

In the next five to ten years, this is exactly the kind of advance that Akhtar says he hopes the Ability Hand can achieve. In particular, he says that Psyonic is looking to work with universities to develop novel surgeries, such as connecting a user’s existing tendons to their prosthesis, for a more seamless integration. Akhtar says this work could also inform the future of service robots, who, like prosthesis users, are learning to use their robotic limbs in a more “human” way.

Wherever these technologies go next, one thing is certain: humans will need to seriously improve their arm-wrestling skills if they want to compete against prostheses.

You Might Also Like