How a War Correspondent Protects His Mental Health

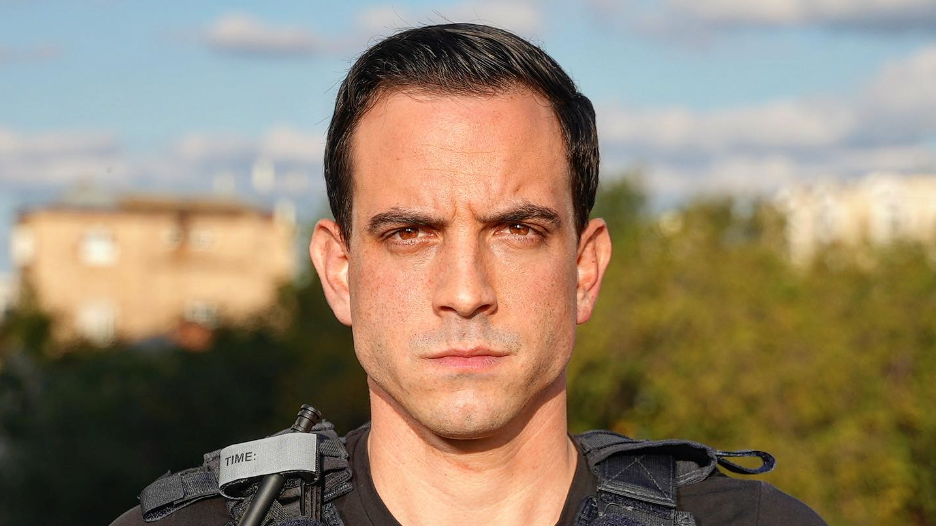

Trey Yingst has a calm about him that is almost unnerving. As a war correspondent, Yingst is currently stationed in an extremely dangerous region of the world right now—Israel and the Gaza Strip. Yet even as he discusses almost dying in an airstrike an hour earlier, he is calm. Matter-of-fact. Sobered.

"Fear is something that, if you're not careful, can put you in a very dangerous situation," Yingst said on the Men's Health Instagram Live show, Friday Sessions, as orange flashes of airstrikes within Gaza illuminate behind him. "You've gotta have the right amount of fear."

For the past decade, Yingst has traveled to regions most are fleeing, reporting on the realities of war, violence, and human conflict. The seasoned journalist has reported out of war zones in Ukraine, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Currently a foreign correspondent for Fox News, he is stationed in Israel reporting on the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Yingst recently joined Friday Sessions from the Israel-Gaza border to discuss how he manages his mental health in the most extreme of situations. Just an hour and a half prior to his conversation with Friday Sessions host Dr. Gregory Scott Brown, Yingst said he and his team were running for cover under rocket fire with one rocket hitting about 100 feet away.

"It was a miracle that no one was injured or killed," he said. Himself included.

Yingst calls his reporting on the escalating conflict in Israel "one of the most challenging assignments [he's] ever been on." The life-threatening situations, the sleepless nights, the constant smell of death. Yet even when Yingst is covering from shrapnel-spraying airstrikes, he works to maintain essential clarity of thought.

"If I allow my mind to get out of control, I'm putting myself and my crew in more danger," he said, citing circular breathing techniques as his go-to coping mechanism during tense situations.

But the heavy lifting of Yingst's mental health care is done when he steps away from assignment, preparing himself for moments like these when trauma is ever-present and time for processing is minimal.

The Time to Take Care of Your Mind is All the Time

"I always tell people that I prepare my body and my mind during times of peace," he said. Yingst mentioned that prior to his current reporting in Israel and Gaza, he was exercising and cold plunging each day to maintain a high level of physical and mental endurance.

"You learn control over your mind and your breathing in a cold plunge," he said. "Anyone who's ever done cold exposure, you get in and your body wants to take over it. You're panicking. Part of it is learning to control your breath and your mind, reminding yourself that it's only temporary. If you can slow down your breathing, you're in control. Those things are applicable to the field."

Being a war correspondent is far from a 9-to-5 gig. Yingst is on the job 24/7, often going without sleep while living in the world's most dangerous territories. As much as war requires mental toughness, so does a return to any sense of normalcy after such grueling conditions.

"War has a way of changing your mind in a way that is difficult to describe. But it is just something that anyone who's ever been to war will tell you about," Yingst said during the Instagram Live. "You have to reintegrate into society. You have to remember that you can go to the grocery store and ask people how their day was and what the weather's like...You have to almost retrain your mind to be a normal person."

Yingst said he's learned to be patient and loving toward himself during this "reintegration" and "retraining." But this grace toward oneself extends far beyond the trauma of war—Yingst believes it's universal.

"You don't have to be a war correspondent to be down about something," he said. "But figure out what [coping techniques] work for you and start to implement them. And remind yourself that you're not gonna feel better in one day. But you have to know there's a path and there's an end goal. If you keep all that in mind, there are brighter days ahead."

But often, Yingst is meeting people during their darkest days—in the midst of war that has killed their families, destroyed their homes, and upturned their lives. In those moments of extreme emotional turmoil, he recognizes optimism is often unhelpful. Those potential "brighter days" aren't a comfort. Empathy, however, can be.

"You try to give people a hug and tell them it's OK. But it's not OK. It's not OK," he said. "People are losing their loved ones, right? We just went to a small community in southern Israel and we met a mother whose son is being held hostage by Hamas inside Gaza—and it's not OK. Her situation isn't OK. And so you can't tell them it's gonna be OK. I just gave her a hug before we left and I said, 'My heart is with you. We're gonna tell your story.'"

He added, "And I've been texting with people I know inside Gaza who are not members of Hamas—just Palestinian civilians or journalists who have lost friends this week. You can't tell them it's OK, because war is ugly. It is horrific. It's horrible. I hate war and the people who pay the highest price in war are not the army. It's not the militants or the members of Hamas—it's civilians."

But even as the harrowing orange flashes of airstrikes illuminate Gaza behind Yingst, he still remains hopeful about the state of humanity, using his reporting as a way to "shine light in dark places.

"My biggest takeaway from covering conflicts and from covering tragedies and natural disasters around the world is that humans are inherently good," he said.

Watch the whole conversation below:

You Might Also Like