Do You Want to Be Right—Or Do You Want to Be Happy?

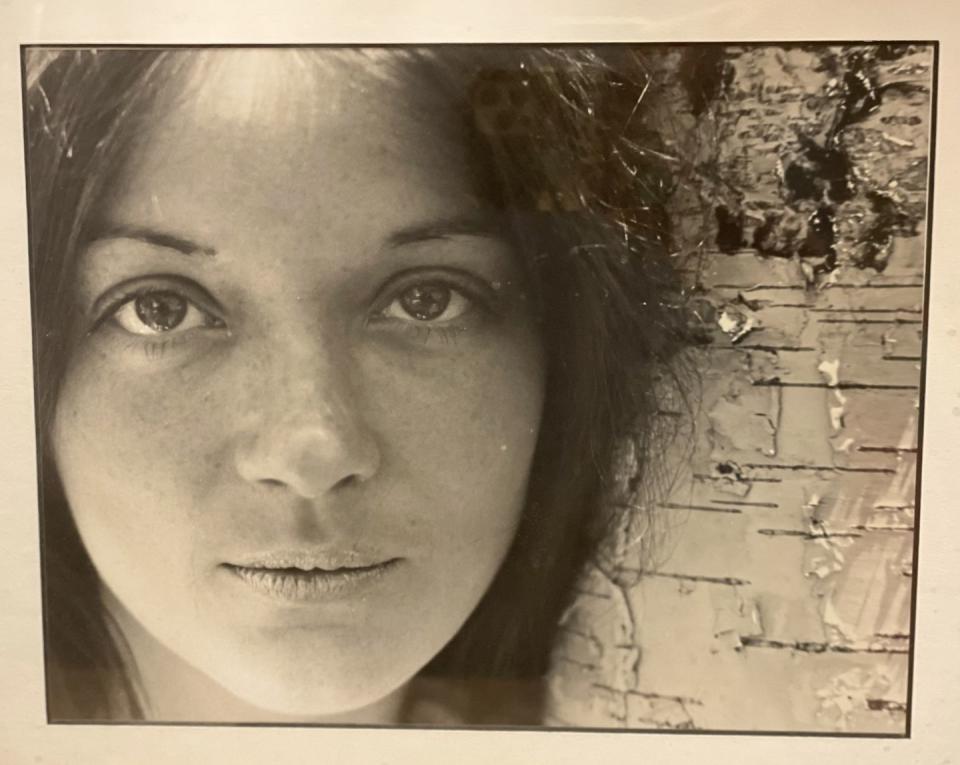

It was at the bedside of a dying friend that I faced the absurdity of my overwhelming need to be right. I’d met Mary Lou when I was an eager, insecure teenager of recently divorced parents. The epitome of downtown intellectual chic, she lived on Rivington Street, waited tables at Dojo, wore combat boots to ward off the junkies sleeping in her doorway, and—a few years before Melanie Griffith in Something Wild—sported a Lulu haircut.

She was part of my father’s crowd. I lived with my mother, who worked full time, but on weekend visits to my father I met a stream of intriguing characters, and among these Mary Lou was my favorite. She recognized my curiosity and yearning; in time, she became an older sister, auntie, mentor, and guide. She’d take me to old Buster Keaton movies. She’d take me shopping in the Village for vintage clothes. She encouraged therapy and even introduced me to my first therapist. Eventually, she went back to school and became a therapist herself. Even in her final months, after she was diagnosed with cancer at age 50, she continued to meet with her shrink. “Just because you’re dying,” she said, “doesn’t mean you get to stop doing the work.”

One afternoon during a summer heatwave, I sat by Mary Lou’s bed in her comfortable, air-conditioned hospice room, chatting about nothing in particular. Somehow, we got onto music, to Aretha Franklin, and the song “Respect,” which came out when Mary Lou was eighteen and I had yet to be born.

“You know, Otis Redding wrote that song,” I said.

“No, he didn’t,” she said.

My body responded as if I’d stuck a wet finger into a light socket before the words “Yes, he did!” rushed out of my mouth. Here was the smartest person I knew—it seemed imperative to correct her.

Mary Lou placed her frail hand over mine and looked straight into my eyes. “You don’t need to be right,” she said. “I still love you.”

That night, I told the story to a music producer friend of mine over the phone, commiserating but also, in those pre-Google days, for corroboration.

He said, “Otis Redding did write ‘Respect.’”

All I wanted to do is run back to that hospital room, shake my dying friend, and tell her, “See? I was right! See?! See?!?!”

At 51, I’m now a year older than Mary Lou was when she died. From the way I’ve been dining out on this story for two decades, you’d think I’d learned my lesson. Still, a volatile part of me is hounded by the relentless need to be right. I’m still litigating arguments from college, high school, and before that.

A therapist of mine asked me, “Would you rather be right, or happy?”

My answer: “I’m happy when I’m right.”

I’m most set off by people who also need to be right especially if they speak in absolutes, make blanket statements, savor debate, and worst of all, lack a sense of humor or irony. Could be anyone—a stranger at the bakery, colleagues, friends, never mind family. Naturally, nobody sets me off more than my wife, Emily, and she doesn’t even have a hang-up about being right.

With Em, I don’t need to be right as much as I fear being wrong.

A few weeks ago, when she asked me to put my clothes in the hamper, not on the floor, I looked at her wild-eyed. I’d only put them on the floor because she once told me that if the hamper was full not to stuff it more. At least that’s how I remembered it.

Turns out, I didn’t even hear her accurately. She really said, “Did you drop your clothes on the floor because they were wet from hiking?”

Surprised at the vehemence of my response she asked, “Why are you so angry?”

I stared at her in disbelief.

How the hell was I supposed to know?

From an evolutionary perspective, says psychologist Rick Hanson—co-host of the weekly podcast Being Well—there’s good reason why are we so deeply invested in our views. “If someone attacks your view or dismisses it out-of-hand,” says Hanson, “they’re dismissing you out-of-hand.”

Our view is inextricably associated with our sense of self—the “I” who holds the belief, and the “me” that is served by it. So, if people are attacking our beliefs, they’re attacking us. “One of the functions of the nervous system is to form a view about reality that helps keep us alive,” says Hanson.

I grew up in a family of voluble, table-slapping arguers. They didn’t just argue about facts, they argued about opinions, they argued about taste. Can you have the wrong taste? I guarantee you can. The message in my family: I got the answer, not you. I’m right and you’re wrong. If you don’t agree with me, you don’t understand me. (Or, my interpretation: If I’m not right, I must be a piece of shit.) Being right wasn’t just a matter of ego gratification, but of emotional survival.

The relational answer to the question who’s right and who’s wrong, according to couples therapist Terry Real, is: Who cares? “Objective reality has no place in an intimate relationship,” he says. It’s about two people, with different backgrounds and experiences and attitudes learning how to honor those differences. “Open your heart with generosity,” he says, “and respond with compassionate curiosity about your partner’s subjective experience.”

So how should you handle yourself when your point of view is challenged and your primitive systems believe that defending it is a matter of survival? The best thing to do, says Real, is shut your fucking mouth. Take a breath. Count to ten. Walk around the block. Meditate. Do some push-ups. As I contemplated this, a montage of arguments with my wife unspooled in my mind’s eye; all the times I couldn’t stop the words pouring out of me, disbelieving what I said as I said it.

“If you came to me as a client,” says Richard Schwartz, a psychotherapist who developed Internal Family Systems (IFS), “I would have you focus on that part of you that is so determined to get it right. I would get you to be curious about it and ask: What would happen if you didn’t correct someone when you thought you were right?”

When my wife confronted me about putting the clothes in the hamper, I got mad before I knew why. IFS labels this reactive part of us, “Firefighters”; Real calls them the “Adaptive Child.” (Same difference.) There’s nothing subtle about these so-called Firefighters: they’ll kick in the door, wreck the house, screw the consequences. “I would ask the Firefighter to let us go to the part it’s protecting that feels worthless,” says Schwartz. “We could go to that part and learn where it’s stuck in the past and get it out of there. Then this protective part is not quite so volatile.”

Ah, if only it were that easy. Of course, there is nothing quick or facile about any of this. It takes a lot of time and effort—and I wouldn’t suggest trying something like IFS without a licensed practitioner. In interviews, Real and Schwartz make their theories sound effortless, but don’t let them fool you; they put in the work themselves. And regression is normal. We stumble constantly.

When Schwartz notices the rush that comes when his Firefighter is provoked, his adult-self steps in and says, Okay, I get that you really want to correct this person. Just let me handle it. You don’t have to take over. Beyond that, he tells the part, I see you. I understand why you feel the way you do and I appreciate the job you’ve done to keep me safe. “I will feel a physiological shift as the part calms down and recedes,” says Schwartz, “I’ll notice my heart’s open again, my mind is clear again. Now my Firefighter trusts that in almost any situation. Except with my wife.”

He laughs and I say, “So, your wife’s the greatest gift in the world to you, right?”

“Totally,” says Schwartz. “I call her my tor-mentor. She’s mentoring me about what I need to heal.”

It’s a shame that Emily and Mary Lou never met but in many ways, Mary Lou prepared me for Emily. She let me know how much work relationships are and how to cherish a partner that is fierce, self-aware, and loving.

Nobody made Mary Lou laugh like the great silent film comedian, Buster Keaton. In the ’80s and ’90s, we saw old prints of his movies: Our Hospitality, Steamboat Bill Jr., Go West, The Cameraman. Buster’s characters were often unassuming guys, narrowly focused and determined in impractical circumstances—even when he played a fop like the rich socialite abandoned on a deserted ocean liner in The Navigator (Keaton’s favorite film) who boils a single egg in an enormous pot of water.

Buster made cluelessness endearing because it came without guile. Mary Lou delighted in his sexual predicaments. Always courtly in his role as the pursuer, Buster also lived in abject terror of women—their allure, power, and mystery. The romance in his movies is characterized by longing and defeat.

“The character just does his best,” Keaton once said of himself on screen, “and there’s your comedy. No begging.”

Buster’s version of right is not about being right but about knowing what you want and pursuing it and not taking failure personally. No begging.

I love that Schwartz honors his wife as his tor-mentor. The best we can hope for in a committed relationship is to have a merciful tor-mentor because our partners are going to see us at our ugliest. They are witness to our most tortured moments. I know that even when we’re fighting, even when I’m crossed-eyed with anger, my wife is never fucking with me. Even when she’s pissed off, too. And that’s no small thing.

If it sounds like I’ve got a handle on any of this, talk to me in five minutes.

Sometimes, though, in the middle of an argument, I’m able to catch myself clinging to that need to be right. If I pause ever so slightly before steamrolling into battle, I can hear the sweet derision of Mary Lou’s throaty, contagious laughter, reminding me that nobody cares, and that insisting on being right means I’m missing the point.

You Might Also Like