Want to Feel Proud of the U.S.? Meet These 30 New Americans

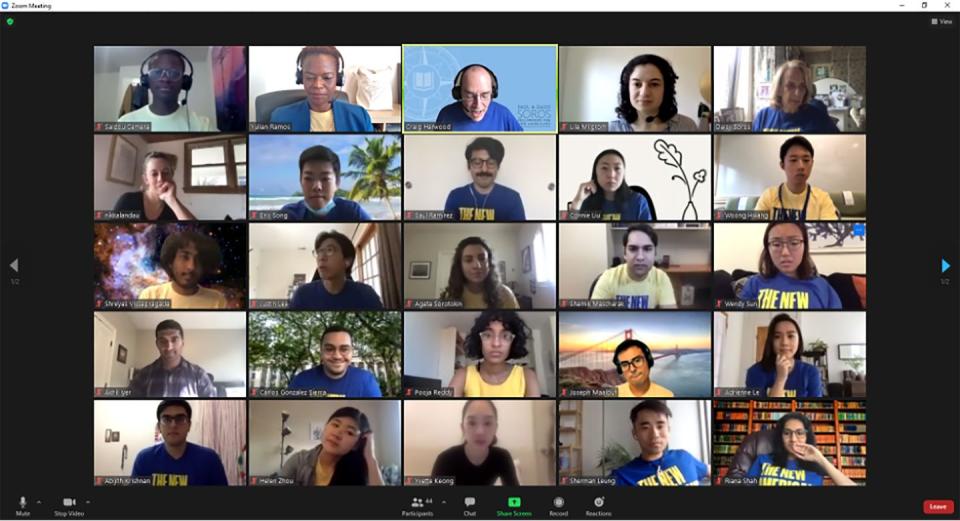

Last month, as the nation entered the final weeks of one of the most bitter and divisive political battles in its history, a 23-year-old philanthropic organization called the Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowships for New Americans held a remarkably pleasant and united-feeling Zoom party.

It was 2 p.m. on a Friday, and 30 graduate students—each either an immigrant or the child of immigrants to the United States—had joined a call hosted by Craig Harwood, the group’s director, and Daisy Soros, the philanthropist who created the fellowship with her late husband, the civil engineer Paul Soros. (If the last name sounds familiar, it’s because Paul was the older brother of billionaire investor George Soros.)

The students had received news earlier in the year that they had been chosen from more than 2,000 applicants to receive a $90,000 grant each to be used in the pursuit of their studies. Some of them had already met Soros and the staff, but this was the first time they had gathered as a group. Among them were future research scientists, medical doctors, lawyers, architects, as well as a composer and a poet. Past fellows include former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy and computational biologist Pardis Sabeti, one of Time’s 2015 Persons of the Year.

Almost everyone on the call, including Soros, wore a yellow or blue T-shirt with “The New Americans” printed on the front—different attire from pre-Covid years, when the welcome reception for the fall conference was held at Soros’s Manhattan apartment overlooking Central Park and everyone dressed for cocktails. “I miss seeing you all in person,” Soros said. “We’ll find a way to get together soon.”

The fellows, who are among the country’s top scholars, had been given a homework assignment: bring a small object and be prepared to explain to the group how it relates to the scholar’s life in America. “When Paul arrived in this country, all he had was $17 in his pocket and a Leica camera,” Soros told the group. Like herself, Paul fled communist Hungary in the late 1940s (the couple did not meet until after they had both settled in New York). “I like to think about what that camera signified to him. Was it a mirror to the past, a window to the future? I do know that he remembered it years later.”

Harwood called out attendees’ names, and the screen filled with their faces as they spoke. Some sat at kitchen tables, others on living room couches. Some used stock backgrounds. Despite their different cultural origins, their environs shared a strikingly unified aesthetic: stacks of books, paper everywhere, a few lonely plants—grad school utilitarian.

“Hi everyone, my name is Riana Shah,” said a woman holding up a tattered notebook. “I am originally from India, and I currently live in Cambridge. I’m in a dual program at Harvard and MIT doing a business and public administration degree. This is a journal that my middle school friends from India gave to me as I was leaving home. They wrote all these beautiful messages in the first few pages of the journal, because we weren’t sure when we would see each other again. In the difficult early days of moving, I would often go back to those pages to just kind of remind myself of all the things that they saw in me.”

“I am a third year PhD student at Duke University, and I’m studying brain development,” said a woman holding a small sculpture of a house. “My family is Peruvian, and I lived there until I was 10. The object that I have is made out of volcanic rock from my hometown. I wasn’t able to go back to Peru for 16 years, and so when I finally was able to return, I wanted to feel like I had something from home with me, so I lugged back a whole suitcase of the rock. It was pretty heavy but totally worth it.”

When the Soroses formed the fellowship in 1997, immigration was already a divisive issue in U.S politics. A decade earlier, President Reagan had signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, which made it illegal for companies to knowingly hire undocumented immigrants. But back then even the most conservative politicians pursued a measured approach to the subject. After the act passed, Reagan signed an executive order legalizing the immigration status of minor children of people who had been granted amnesty under the new law. It also stipulated that undocumented children of parents who had green cards or were in the process of applying for them, could not be deported.

The Soroses have been involved in a number of philanthropies over the years, including Midsummer Night Swing, an outdoor dance party at New York’s Lincoln Center, which they underwrote for years. Daisy Soros, who attended Columbia University before getting married, sits (or has sat) on the boards of some of the country’s most prominent institutions, including the Society of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and the board of overseers of Weill Cornell Medical College. The couple founded their fellowship by creating a charitable trust of $50 million. They gave another $25 million to the trust in 2010.

Paul worked various jobs after he arrived in the U.S. and scraped together enough money to attend the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, where he studied engineering. He specialized in maritime infrastructure, inventing new systems for loading and unloading cargo ships. His company, Soros Associates, designed and built some of the world’s largest ports. (His brother George charted a different path, making his own considerably larger fortune in international investment.) Not long before he died, in 2013, Paul described his vision for the fellowship in a video interview: “The idea was to build something that shows that immigrants, or new Americans, make a real contribution to this country.”

Daisy Soros followed along as each fellow explained his or her object, occasionally clapping her hands and offering encouragement. Early in the call she told the group, “I once asked a new fellow who had also been awarded numerous scholarships to tell me the difference between our fellowship and the Rhodes [scholarship]. He said, ‘Yours has a heart.’”

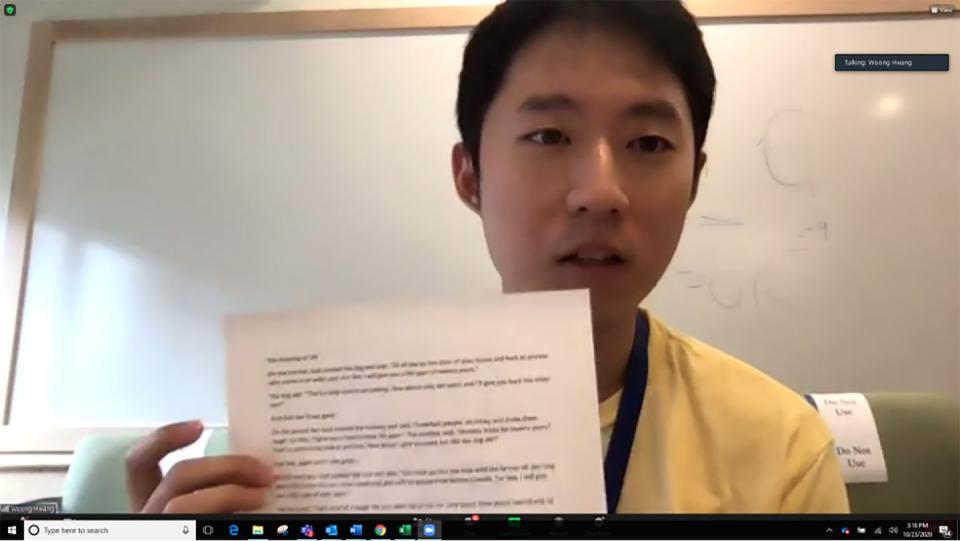

One of the last fellows to speak was Woong Hwang, an MD/PhD student at Yale, who held up a sheaf of white paper covered in black type. “I have here 50 of my mother’s carefully selected jokes,” he said. “I was born in South Korea, and my family moved to the States when I was 15, when my mother received a green card through her job as a nurse. She couldn’t speak English very well when we first got here, and she decided to practice by telling her patients a new joke every day. Jokes have a storyline and people only laugh when they truly understand the nuances. I remember seeing her in front of the mirror at night practicing her jokes, and it reminds me how hard my parents worked to overcome the challenges they faced as immigrants.”

Then, with only a little egging by the group, he told a joke.

You Might Also Like