Wailing, writhing and primal screams: inside John Lennon and Yoko Ono's reviled anti-Beatles band

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

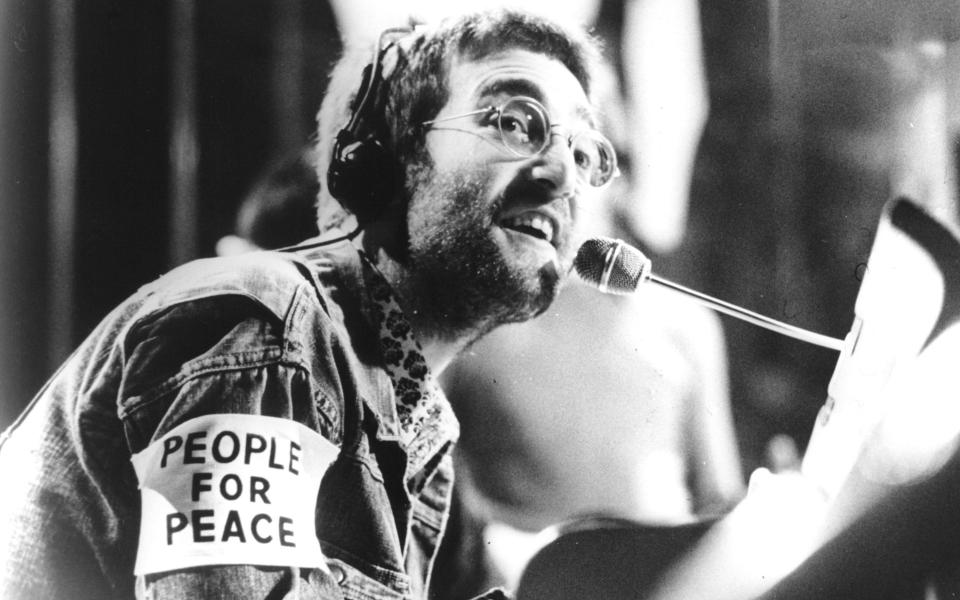

For the 20,000 rock fans gathered in Toronto’s Varsity Stadium on the night of September 13, 1969, it was an extraordinary sight. Performing on stage was a lavishly bearded John Lennon, dressed in a white suit and still a member of The Beatles, having completed the recording of Abbey Road just weeks previously. But the musicians accompanying Lennon as he ploughed through early rock ‘n’ roll standards were not Paul, George and Ringo. Instead, his backing band comprised guitarist Eric Clapton, former Manfred Mann bassist Klaus Voormann, future Yes drummer Alan White – and Lennon's wife. It was the first live concert by The Plastic Ono Band

The make-up of Lennon’s band was eye-catching enough. As was the fact that he was playing live at all: the 28 year-old hadn’t performed in front of a concert audience since the Beatles stopped touring three years previously. But what really grabbed the crowd’s attention on that warm autumn night was the object at Lennon’s feet.

There, on the stage, a large white sack writhed to the music. Inside it, Yoko Ono was twisting and contorting herself. By the time the band had completed six songs, the avant-garde artist had emerged from her sack. Ono then performed two numbers in her distinctive high-pitched wail. The second song lasted almost 13 minutes and ended in a volley of screeching guitar feedback. US rock critic Robert Christgau described Ono’s vocal style as “keening”. Lennon himself said her performance was “half rock and half madness” and that it “really freaked out” the crowd.

The Toronto gig certainly left its mark. Looking back today, Voormann, who met the Beatles in his native Germany, recalls Lennon's audacity and the shock it caused.

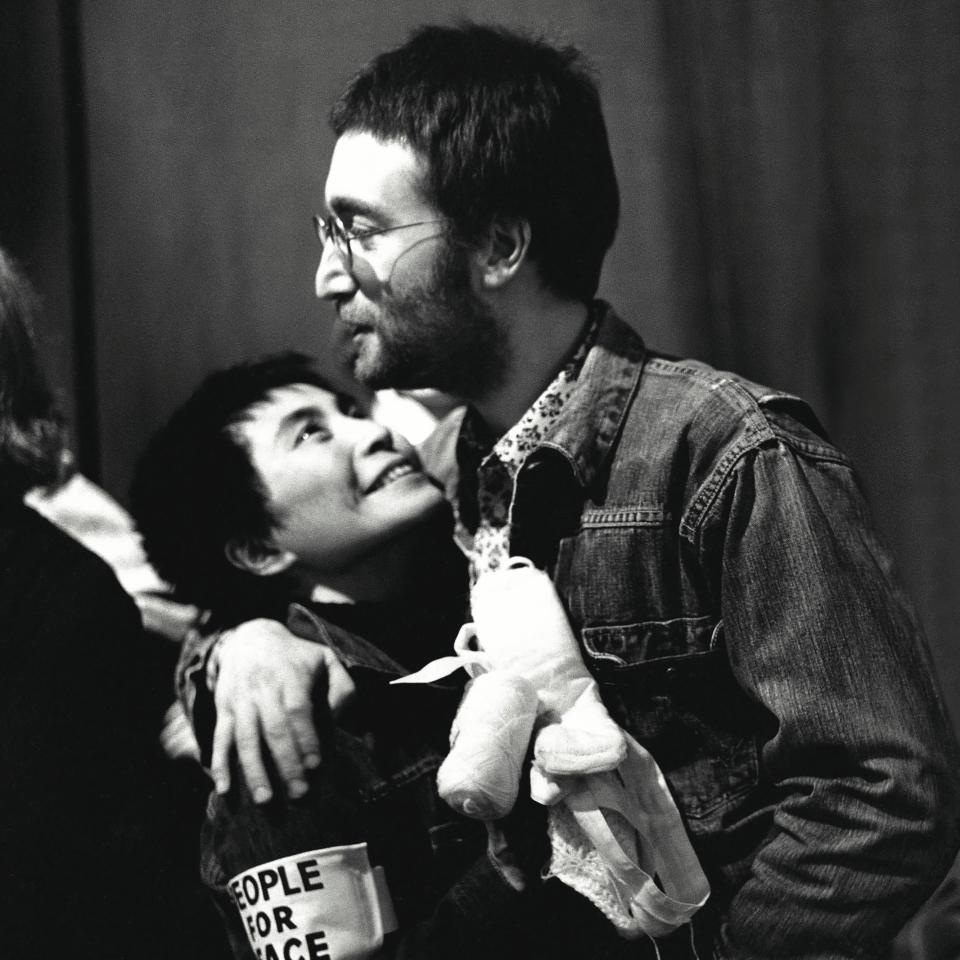

“How can a Beatle who is world famous go up there and have Yoko doing her thing, which nobody in the audience knew or expected anything about? That’s brave of [Lennon]. And the way he was treating Yoko when she was screaming – he was hugging her. It was just amazing,” says Voormann, 82.

I tell him that Ono’s performance, which was recorded, is not easy to listen to. “It wasn’t easy for the audience either,” he chuckles.

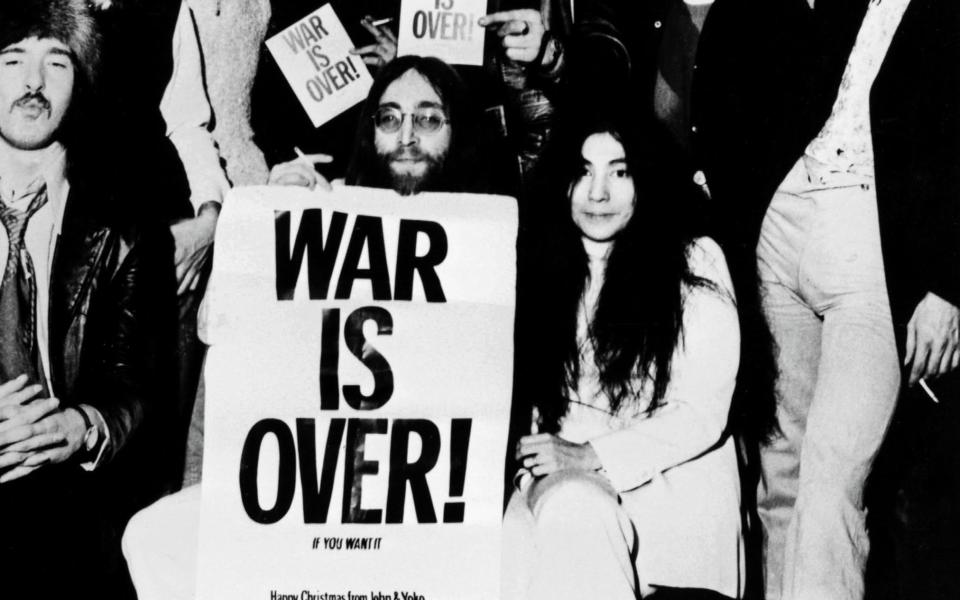

The Plastic Ono Band were the anti-Beatles. A side project started by Lennon and Ono as the world’s biggest group were imploding, the Band were part musical collective, part left-field art concept (audience members were told they were members of the group) and part an actual art installation: the original Plastic Ono Band was a sound and light sculpture set up in the Apple press office in London. The Band underwent multiple line-up changes and released numerous experimental albums. Their music was as far removed as possible from the cheerily simple Merseybeat of 1963’s She Loves You or the hippy idealism of 1967’s All You Need Is Love.

Because of this, the Plastic Ono Band are often dismissed as an eccentric footnote in the broad sweep of Beatles history. But as we reach the 50th anniversary of Plastic Ono’s first albums on 11 December, are they due some form of critical re-appraisal? A glossy new book certainly makes the Band’s mission and music seem more than indulgent garnish. John & Yoko/Plastic Ono Band is a hardback compendium of first-hand accounts about the band drawn from interviews over the years.

It contains photos, lyrics, drawings and letters, and will be as interesting to Lennon completists as The Beatles Anthology was to general fans 20 years ago. In the book, Lennon, who died in 1980, claims that the first Plastic Ono album was “the best thing I’ve ever done”. And in the preface, Ono describes the band as “the most musical and imaginative group in the world”.

Voormann, who lived with Harrison and Starr in London and designed the sleeve for the band’s Revolver album, says that Lennon relished the freedom of Plastic Ono after years of being a Beatle. “John would have been a very unhappy man if he’d have carried on [with The Beatles]. Until he met Yoko [in 1966] he was frustrated, and when he met Yoko he was not frustrated. Suddenly he started to live,” says Voormann.

According to him, things were so bad for Lennon by the mid-1960s that he contemplated suicide. He recalls a time when the pair were together in the garden of Lennon’s house in Weybridge and the singer was angrily yanking leaves off a bush (Voormann thinks he was tripping on LSD at the time). “There was this big heap of leaves on the ground and I said ‘Hey John, the bush can’t help it that you are in bad shape.’ And that’s when he said he didn’t want to live,” Voormann says.

Voormann’s claim that Ono was Lennon’s saviour is a refreshing counter-narrative to the oft-repeated Beatles platitude that Ono was some kind of destructive influence. Quite the opposite. She gave him purpose, he argues.

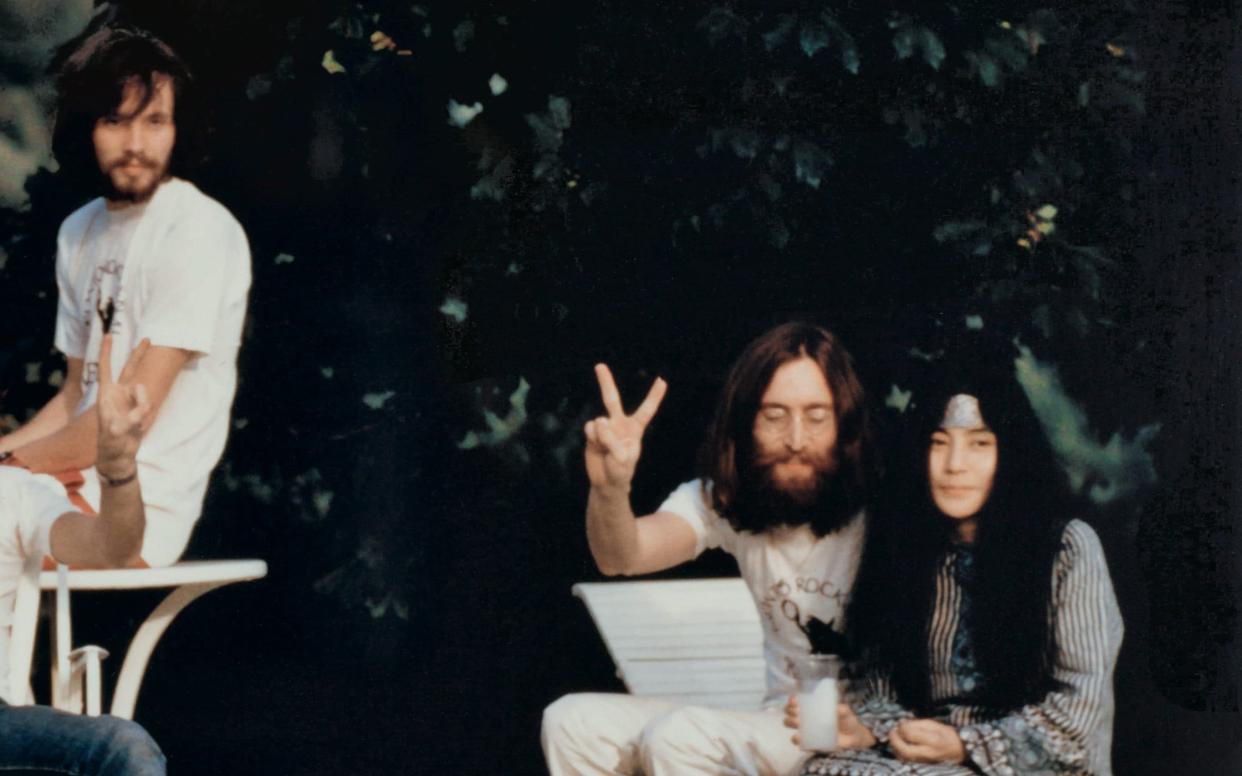

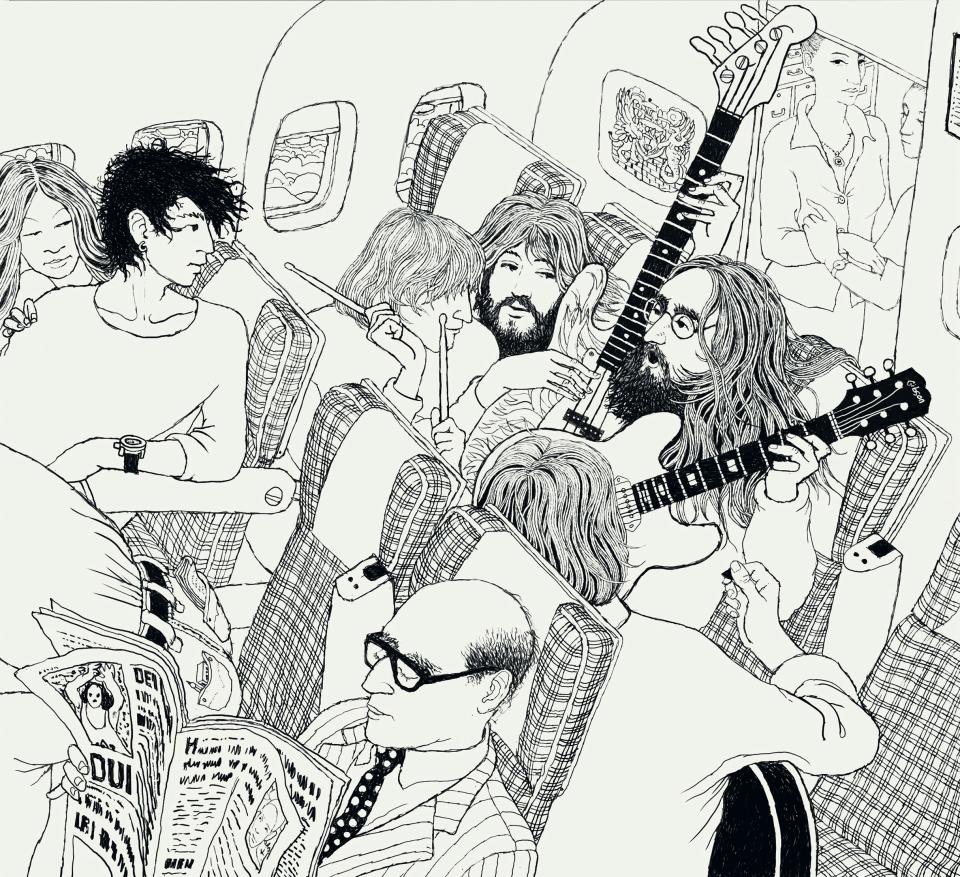

Lennon and Ono married in March 1969. That was the year of their famous “bed-in” peace protests which saw them release the first Plastic Ono single, Give Peace A Chance. Then came Toronto. So last minute was the band’s formation that Lennon, Clapton, Voormann and White first rehearsed on the plane to Canada, strumming unplugged electric guitars that they couldn’t even hear. It was also on this flight that Lennon told Beatles manager Allen Klein that he was leaving the Fab Four. The chaos of was captured in a line drawing by Voormann, his Revolver style very much in evidence.

Plastic Ono courted controversy. In early 1970 they played their single Instant Karma! on Top of the Pops. In a stunt that was clearly missed by the BBC, Ono sat on stage knitting with a sanitary towel taped across her eyes. She was, she said, taking a stand against female oppression. Voormann was there. He says the sanitary towel was an act of artistic provocation, which is exactly what Plastic Ono were about. “You want to provoke. Maybe the director could have said ‘You have to take this tampon off your head, you can’t do that’, but nobody did. She actually dared to do something that naughty,” he says.

It was against this backdrop that Plastic Ono entered the studio in September 1970 with producer Phil Spector to record their first albums. Lennon and Ono had just undergone six months of Primal Scream therapy under the guidance of psychotherapist Arthur Janov. The therapy encouraged Lennon to re-live painful childhood memories, such as being largely abandoned by his parents. The songs that emerged for his album, called John Lennon/ Plastic Ono Band, reflected this experience. “John’s songs were a literal expression of his feelings,” says Ono in the book.

In opening song Mother, Lennon set out his emotional stall. “Mother… I still wanted you/ But you didn’t want me,” he sang. The closing refrain of “Mama don’t go/ Daddy come home” is painful to listen to as Lennon’s screams become more and more unhinged. His honesty was repeated across the album, notably on the song God in which he famously sang, “I don’t believe in Beatles/ I just believe in me/ Yoko and me.”

This rawness applied to the recording process too, Voormann says. The musical arrangements and Spector’s production were kept simple. The band was just Lennon, Voormann and Ringo Starr on drums, although Spector and Billy Preston played piano on a couple of tracks. Unlike on Beatles records, there were few overdubs and no complicated mixing techniques. “It was so direct,” explains Voormann. “The tracks were just done live and raw. That’s the best way to express feelings… For me, this is an LP that will never die.”

But Lennon’s album was only half the equation. In typically out there fashion, the band recorded an Ono album called Yoko Ono/ Plastic Ono Band at the same time, to be released on the same day and with an almost identical cover as Lennon’s record. This chorus-free album contained more of Ono’s distinctive throat singing (or “revolutionary vocal sounds”, as she puts it) over freestyle jams. Songs recorded included the X-rated orgasmo-jam of Open Your Box and the lolloping funk lament of Greenfield Morning I Pushed An Empty Baby Carriage All Over The City, a possible reference to a miscarriage that Ono had suffered. Lennon had originally wanted to call his album Primal and Ono’s album Scream.

Today, Ono’s record sounds like an occasionally thrilling, often baffling and consistently mind-bending space rock odyssey. It’s tough going: of the album, Ono says she used her vocal training and technique “to discover primeval expressions, sounds and rhythms from deep within that could also metaphysically reconnect us with our souls and our collective unconscious”.

I ask Voormann what Starr made of all this metaphysical reconnection. After all, the down-to-earth Beatles drummer had just released Sentimental Journey, an album of cheesy ballads and Cole Porter standards. But Starr was down with the bizarre. “Yoko would go up to the microphone and just started screaming – Waaaaaaaa – and Ringo and I would go booka-backa-booka-backa and just do a crazy beat. We would look at each other and go ‘Oh yeah’. Ringo was open to it. He did great experimental stuff even though you think he’s not exactly avant-garde,” says Voormann.

Some critics mauled the albums. Rolling Stone’s Lester Bangs called them “the ego-trips of two rich waifs”. Lennon’s album performed reasonably well, reaching number eight in the UK and number six in the US. Ono’s failed to chart in the UK and reached number 182 in the US. But compared to the other Beatles’ solo efforts, Lennon’s album was a failure. George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass was released just two weeks earlier and topped the charts on both sides of the Atlantic for weeks on end. Paul McCartney’s solo debut earlier in 1970 was almost as successful, and even Ringo’s Sentimental Journey reached number seven in the UK.

Lennon biographers have claimed he was upset at his relative commercial failure. Voormann says not. Plastic Ono was not about selling records, it was about Lennon striking out. As the singer told US journalist Howard Smith in 1969, he no longer wanted to be John Lennon The Myth.

Ono says that Plastic Ono gave her and Lennon “total freedom”. Listening to their output, it's not hard to believe it. And when it comes to re-assessment, the intimate confessions of popular culture’s most famous couple were certainly groundbreaking. As Rolling Stone put it in 2016, “in the pre-social media age, this was reality show audio theatre starring a wildly famous couple” at their most private. Musically, the pair – particularly Ono – kicked the door open for the DIY ethos of punk and the experimentation of new wave. You can hear The Slits and Public Image in the music.

When Lennon first heard the B-52s’ Rock Lobster almost a decade later, he excitedly exclaimed that they were “doing Yoko”. The echoes remain today. There are clear parallels in both subject matter and glee of delivery between Open Your Box and this year’s controversial number one WAP by Cardi B featuring Megan Thee Stallion. Perhaps Plastic Ono were half a century ahead of their time after all.

Voormann certainly thinks that further re-appraisal is due. “Plastic Ono will grow on people. I think people will find out about it sometime and there might really be a wave of [rediscovery],” the bass player says. “It will definitely be seen as one of the most important statements ever made.”

John & Yoko/Plastic Ono Band by John Lennon and Yoko Ono is published by Thames & Hudson